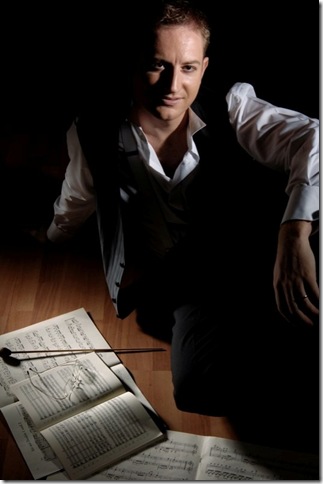

Carter Brey and Christopher O’Riley (Dec. 19, Kravis Center)

World premieres are always special, but they don’t always suggest that they will make a lasting impact on the culture.

But composer Justin Dello Joio’s Due per Due, which was given its debut by cellist Carter Brey and pianist Christopher O’Riley, is a worthy new work that deserves to be added to the programs of ambitious cellists looking for something new to add to their solo programs.

The first of its two movements began with fragments and wisps of things, including a passage for high harmonics against a clinking of glass in the upper reaches of the piano. But the heart of the movement was a song, highly emotional and lyrical, but also somewhat restrained, just shy of total release.

The second movement, a perpetual-motion romp, had Brey and O’Riley almost continually playing rapid scale figures, which toward the end were regularly interrupted by sudden chordal outbursts. It’s a tough piece to play, but rewarding to listen to, and Brey and O’Riley gave it a stellar performance.

The piece received a warm response from the midsized house, which included the composer himself, who stood and applauded his interpreters.

Also on the program was a somewhat rough-and-ready version of a Bach gamba sonata (No. 3 in G minor, BWV 1029) in which Brey was noticeably out of tune with the piano until midway through the first movement. The principal cellist of the New York Philharmonic showed his true mettle in the second movement, demonstrating a noble, lovely tone that suited the music admirably.

The second half of the program was devoted to the Cello Sonata of Edvard Grieg (in A minor, Op. 36), and here, too, Brey’s beautiful sound quality made the most of the Norwegian composer’s distinctive melodies. O’Riley was a fine accompanist, restraining himself when he could easily have let loose with the pyrotechnics of Grieg’s piano writing.

The encore was a tasteful, elegant Daisies (Op. 38, No. 3), a transcription of the Rachmaninov song. – G. Stepanich

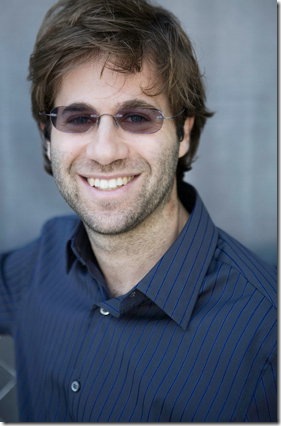

Palm Beach Symphony (Dec. 15, Society of the Four Arts)

A very large audience at the Society of the Four Arts on Dec. 15 heard what the late Sir Thomas Beecham called “lollipops” — sweet short pieces of a classical nature – for the first concert of the Palm Beach Symphony season.

It also marked the first concert with Ramon Tebar as the group’s music director, and he’s a man with much to celebrate these days: he just won the Henry C. Clark Conductor of the Year award from Florida Grand Opera, and he’s a new father to baby Isabel, born Dec. 8, a week before the concert.

Aaron Copland’s Three Latin-American Sketches began the program. The first sketch has sharp, cutting, staccato rhythms with dissonant tonal passages, distinctly Copland. The second was sensitive and lingering, shaped nicely by Tebar. Working hard in the last sketch, the strings shone and the percussionists outdid themselves.

Next followed Samuel Barber’s justly famous Adagio for Strings. Putting down his baton, Tebar led a golden interpretation, bringing out the long elegiac line as the strings swept up to a climax — a deafening long pause, then the downward glide to a pianissimo ending. One could hear a pin drop. Cautiously, the audience picked up on a well-deserved ovation for this work, which belongs in the pantheon of great string pieces by Elgar, Holst, Grieg and Warlock.

Before intermission, Copland’s Appalachian Spring got an inconsistent reading. Written in 1931 for the savvy Martha Graham (whom I knew) and her dance company, she took her lead from Igor Stravinsky’s association with Serge Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes. Copland was savvy, too, incorporating the Simple Gifts hymn of Mother Anne Lee, whose Shaker settlements stretch along the top of the Appalachian Trail in New England.

It was wordsmith Ira Gershwin who coined the title Rhapsody in Blue for his brother George’s 1924 classical concerto tribute to the jazz world. Venezuelan pianist Kristhyan Benitez shone as the soloist here, with a brilliant and sensitive handling of the keyboard. There were a few fluffs, but overall the piece was a blockbuster, and the audience gave it a standing ovation.

Leonard Bernstein’s Three Dance Episodes from his musical On the Town, about three sailors on shore leave in New York City, had a rousing performance. The brassy first dance set the scene. In the second dance, the clarinet was prominent with trumpet obbligato soaring over incoming strings. In the third dance, Tebar was in his element, visibly dancing on the podium to Bernstein’s catchy tunes. – Rex Hearn

Delray String Quartet (Dec. 3, All Saints Episcopal Church, Fort Lauderdale)

Not every composer wrote string quartets with four more-or-less equal voices.

The earliest quartets, and the quartets of later writers such as Gaetano Donizetti, can often be a workout for the first violin, with the other three instruments playing backup. But much of the canonical repertoire requires all four of the players to be equally able, and the foursome that doesn’t have a deep bench finds musical life to be a struggle.

So it’s a pleasure to report that the new second violinist of the Delray String Quartet, Tomas Cotik, makes a fine addition to this ambitious group, which opened its seventh season Dec. 3 with a concert at All Saints Episcopal Church in Delray Beach.

Cotik, an Argentinian-born musician who has recently taken a teaching assistantship at the University of Miami, replaces Megan McClendon, a one-season replacement for Laszlo Pap, a founding member of the quartet. Pap now leads the Fort Lauderdale String Quartet, which is under the auspices of the Symphony of the Americas.

Cotik also has a strong and distinctive sound, and in most of the concert he and violist Richard Fleischman supplied a vivid, virile middle to the music, with solo work from both men making full impact. This first concert of the season had two major events, the first being the performance of the String Quartet No. 4 of the American composer Kenneth Fuchs.

Fuchs, a Broward County native who studied at the University of Miami before moving on to Juilliard, was on hand to discuss his brief but engaging one-movement quartet, subtitled Bergonzi, in honor of the UM-based quartet for whom it was written. It’s a relatively light but tautly constructed piece built on a three-note rising motif first sounded by the viola. That trades off with a gentler three-note motif introduced by the cello, and the music soon expands into a busy, energetic sonic tableau, music that sounds very open and very American.

In the middle, the cello motif is transformed into a moody, expectant theme over a pizzicato version of the three-note opening material; in the last section, the feeling of purposeful energy resumes. It is a fine piece of music, and the Delray played it well, though with a certain tightness and tension that sounded at times as though the players were somewhat too concerned with precision.

Despite its speedy tempo and offbeat accents, this is essentially positive, forthright music, and it would have benefited from a greater sense of relaxation and ease. Still, it was impressive that the Delray began its season with a piece of recent contemporary American music, which to my mind is the logical core repertory for this quartet.

The Second Quartet of Johannes Brahms (in A minor, Op. 51, No. 2), which closed the concert, is one of his most familiar pieces of chamber music, and the Delray gave its rolling first movement a sound that was well-balanced and elegant. The short ritardando transition passages, though, slowed things down a little too much, which hurt the narrative momentum.

First violinist Mei-Mei Luo offered a lovely reading of the main theme of the slow second movement, and the quartet handled the dramatic contrasting section capably. The third movement also was a bit on the slow side for my taste, though I’ve heard other performances at about that speed. But it lacks lift at this pace, and the expectation-and-mystery tradeoff here sounded tentative rather than deliberate. The Allegro vivace was quite good, though, from the standpoint of pace, technical accomplishment and ensemble.

The finale clipped along smartly, and the players attacked the music with considerable force and excitement. The transition to the A major section toward the end was beautifully done, with some fine playing by cellist Claudio Jaffe. Overall, while some of the music was too cautiously approached, this was a strong performance of this repertoire staple, and another important stage in this quartet’s development.

Transportation problems had me arriving late at the concert, so I missed all but the last movement of the opening piece, the Bird Quartet (in C, Hob III: 39) of Haydn. The finale had good ensemble and a snaky kind of energy that was more forceful than the usual powdered-wig approach, and it worked well.

For an encore, the quartet played Fleischman’s arrangement of a piece called Melody, by the Argentine composer Astor Piazzolla. The Delray played it with the requisite high emotion for an effective interpretation of this composer’s music. – G. Stepanich