By Tara Mitton Catao

One could sense the integrity of the tight-knit artistic ensemble that is Rioult Dance NY, the small modern dance company that performed at the intimate Rinker Playhouse at the Kravis Center on Thursday night. Proficient in what they do, Rioult Dance presented a well-balanced program of works choreographed by Artistic Director Pascal Rioult.

In Views of the Fleeting World, the first and the most traditional work of the evening, one could see Rioult’s strong choreographic ties to his unabashed mentor Martha Graham. Though not very cutting-edge, it is a solid work that had some quality. Using good craftsmanship and capable dancing, Rioult was able to create pleasing repetitions of the dancers’ movement phrases that followed the contrapuntal mastery of J.S. Bach’s The Art of Fugue. Lasting 35 minutes and using a limited Graham-like movement vocabulary, Views of the Fleeting World came off as a bit academic and not very memorable.

The nine performers did a good job of not looking cramped while dancing on the small stage of the Rinker. Behind them, the woodblock prints of the 19th-century Japanese master Hiroshige were projected on the backdrop. These simple abstract images were more reminiscent of Impressionist pastels and were a curious choice to pair with one of Bach’s most esoteric musical works. The costumes, which were long, pleated crinoline, unisex skirts that looked like bright red inverted flowers (which the dancers intermittently donned and discarded), were quite beautiful but they also were an interesting pairing with the work.

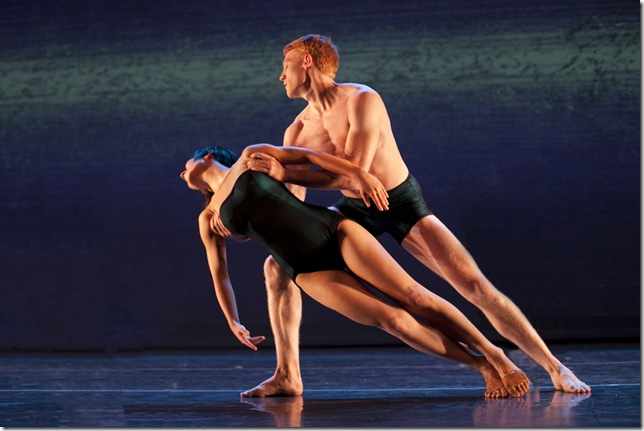

After five rather conventional sections with evocative names like “Wild Horses” and “Summer Wind,” the sixth stood out from the rest. “In Moonlight,” a total contrast to the other sections, a couple (Sara Elizabeth Seger and Brian Flynn) danced sensually on their backs with arms reaching upward to sky in an intimate side by side duet.

City, which used another Bach composition (the Violin Sonata No. 6 in G, BWV 1019) and another projection design by Brian Clifford Beasley, had a more contemporary feel to it and was a more satisfying union.

With a backdrop projection that was a prism of shifting skyscraper facades, four dancers lost and regained their equilibrium as they moved part of the vast crowds that swarm and fill up the streets of the city. As each performed a solo, one acknowledged that although one views crowds in the city as a horde, one needs to recognize that each person is an individual. The concept was simple, but it worked as Rioult’s movement vocabulary was more interesting, and together with the off-balance images of a multitude of glass panes fusing into each other, Rioult managed to create some nice images.

The oldest work on the program and the most intriguing was Wien, which Rioult choreographed 20 years ago just after he started his company. Brought up in France by his mother who was trained as a classical pianist, Rioult was inspired by Ravel’s La Valse.

Ravel wrote La Valse to honor Johann Strauss II, but it is unlike the music of the Waltz King. Ravel’s work is a clouded and volatile work and Rioult very successfully utilized the score to set the mood and create a powerful but not very flattering look at society and the state of humanity in Vienna circa World War II.

The six dancers expertly danced maneuvering in tight quirky formations, creating a murky sense of decadence. The choreography had the look of the rapid mechanisms of a complex, macabre industrial machine. The merry-go-round movements spit out clear images of violent deaths while the sounds of a variety of different waltzes hinted at lost nuances of romance, elegance and grace. The mood veered to growing hysteria as the notes swelled to the “fantastic and fatal whirling” (as Ravel called it) of the waltz rhythm. Rioult created a strong work that his company of dancers performed with dynamic energy, clear focus and a refined sense of drama.

Though the small stage seemed an issue at the beginning of the program, by the end, the dancers were excellent in Rioult’s Bolero perfectly executing on the tiny stage the precise military arm gestures, tight interlacing quadrilles and long, rock-steady balances on one leg. Looking like space-age combatants in their pale silver pants and sleeveless mock turtleneck tops, the ensemble of dancers were a moving screen for lighting designer David Finley’s vibrant illumination, which accelerated right along with the choreography to the familiar climatic finish of Ravel’s familiar Bolero.

Perhaps it was all a little predictable, but still, it was admirably executed.