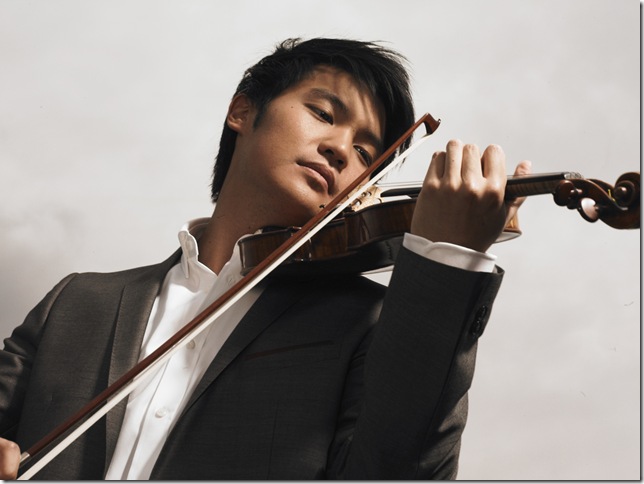

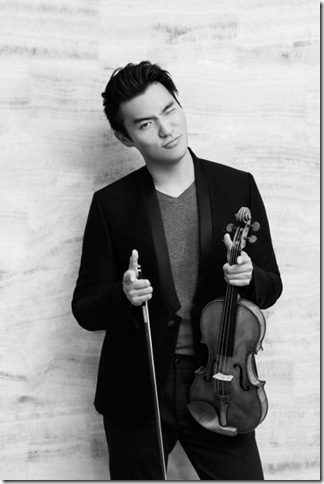

The check-this-out mentality of social media might at first blush seem antithetical to the very idea of classical concertgoing, but that’s not the way Ray Chen sees it.

The young Australian violinist finds his most congenial digital home in the realm of Facebook, but he’s also a master of Twitter and micro-video on Instagram. All of it a means to a worthy end: Getting people away from their Candy Crush obsessions and into a seat for a night of live music.

“I think people nowadays need to have a reason to come to the concert hall. People are being presented with so many choices now. You could just sit on your couch and connect your TV to the Internet and just look up YouTube performances or digital concert halls. Or you could just watch Netflix. There’s so much choice,” Chen said by phone from Bordeaux, France, late last month. “I think classical artists today should try to give people a reason to go, and that’s what I’m doing.”

The Taiwan-born Chen, 25, is a rising star in the world of the virtuoso violin, having won the prestigious Yehudi Menuin and Queen Elisabeth competitions in 2008 and 2009, not long after graduating from the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where he came at age 15 from his home in Brisbane. He studied with the eminent American violinist and pedagogue Aaron Rosand at Curtis, and since leaving school he’s released three albums, the most recent one last year of the Mozart violin sonatas with Christoph Eschenbach as his accompanist.

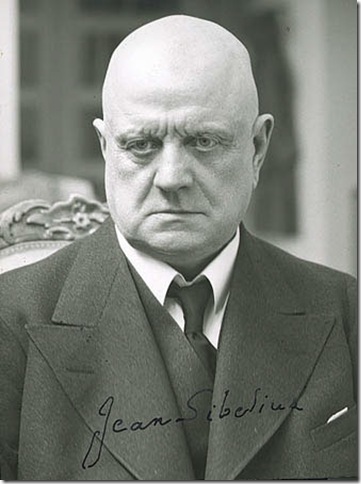

This weekend, Chen is the featured soloist in concerts at the Knight Concert Hall in Miami (Saturday) and the Kravis Center in West Palm Beach (Sunday) by the Danish National Symphony Orchestra, a 90-year-old group founded originally in Copenhagen for the then-new technology of radio. Chen will play the Violin Concerto (in D minor, Op. 47) of the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius, whose salon piece Valse triste also will be on the program.

The concert will close with Danish music: The Fourth Symphony (The Inextinguishable, Op. 29) of Carl Nielsen. The Danes will be led on this American tour by the Romanian-born conductor Cristian Măcelaru, a violin performance graduate of the University of Miami who at 19 became the youngest concertmaster in the Miami Symphony’s history.

“I always like coming back to Miami, because it’s a big part of my life, and a big part of my formation as an artist,” Măcelaru said Wednesday from New York, where he was preparing to lead the Danish orchestra and German violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter in the Sibelius concerto at Carnegie Hall. “It’s such a unique and diverse place in the United States. You don’t meet it anywhere else. It really is its own city.”

Măcelaru, 34, is the conductor-in-residence for the Philadelphia Orchestra, and in 2012 won the Georg Solti Emerging Conductor Award, named in honor of the legendary Chicago Symphony conductor. After leaving Miami — he credits Bergonzi Quartet violinist Glenn Basham and composer Thomas Sleeper with being key mentors during time at UM — he earned his master’s in conducting and violin performance at Rice University in Houston, where he studied with Larry Rachleff and made his debut with the Houston Grand Opera leading Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

Since then he has conducted a stellar string of major orchestras in the States (Chicago, Baltimore, St. Louis, Houston, Seattle, Detroit, among others) and abroad (the Hallé and Bournemouth orchestras in Britain, the Residentie Orkest at the Hague) and regularly returns to his native Romania to conduct and teach there.

Chen, who like Măcelaru lives in Philadelphia, will work with the conductor for the first time this weekend, but he soloed with the Danish group last year in Copenhagen, where he played the Beethoven Violin Concerto.

“Not only a nice orchestra to listen to, but a nice bunch of people as well. That always helps,” Chen said.

Măcelaru agrees.

“It’s a wonderful orchestra. It’s not just an orchestra of great quality, it’s an orchestra of incredible people as well,” he said, and relates the story of how, at a concert in Regensburg, Germany, the stage was somewhat too small for the full group, meaning that one of the string players would have to sit out.

Dropping in on a discussion about this with orchestra members and the personnel manager, Măcelaru asked whether there was a problem. A good problem, he was told.

“‘Nobody wants to take the night off. Everybody wants to play, and so we’re trying to decide who should not play the concert.’ Which really, truly describes how wonderful they are,” he said.

The Sibelius concerto, an audience favorite and one of Sibelius’s finest pieces, is an old friend to Chen, having been his audition piece for Curtis when he was a teenager. He’s played it in the Leipzig Gewandhaus and Vienna’s Musikverein, among other places, and says it’s technically quite difficult, especially the finale, in which the soloist is required to play some “miraculous leaps.”

But there is a substantial interpretive challenge as well.

“Musically, to achieve the kind of wintry, beautiful Finnish landscape at the beginning of the first movement … I learned how to play Sibelius far better after I’d actually encountered snow,” Chen said, Brisbane’s climate being similar to that of South Florida. “It’s such an enjoyable piece. You can really get into it as a performer, and I think the audience can, too. It invites you to reach the great musical depths it has because it’s so well-written, and the ideas are so articulate.”

And it’s a tough one for the orchestra, too, Măcelaru said.

“The concerto is actually perhaps the most difficult piece for the orchestra to accompany,” he said, because “Sibelius plays a lot with the rhythmical aspect of how he writes things,” which often leads to a disconnect with how the music sounds and what’s on the page.

“This is true in all of his music, but in this case, because you have a soloist you’re accompanying, and often times the soloist will play in a completely different meter than the orchestra, and it’s really tricky because as a conductor … are you conducting what the soloist is playing? Or are you conducting what the orchestra is playing, and then with your brain, conducting yourself? It literally is the most difficult concerto to accompany.

“That being said, it’s also one of the most rewarding, because as with all of Sibelius’ music, you have these moments when the orchestra is purely unleashed,” he said.

Măcelaru also took a stab at the curious omission of Nielsen’s music from a lot of American concert programs.

“People often make the mistake of associating Nielsen with the composers around him at the same time, like Sibelius and even Brahms,” he said. “And they make this mistake of expecting to have a similar connection with his music.”

The difference, he said, is that Nielsen’s outlook is basically positive.

“In his deepest moments, Nielsen is all about inner happiness and inner peace, whereas with Sibelius and Brahms the deepest moments are about incredible tragedy and darkness,” Măcelaru said. “And if you don’t understand that, you look at Nielsen’s music, and you think it’s actually shallow … As soon as I started understanding where Nielsen was coming from and the statement that he’s making with his music, then it’s absolutely incredible. It’s so beautiful and reaffirming.”

For his part, Chen has a packed concert schedule in the next few months that takes him, among other places, to Dublin and London later this month; Turkey, Germany and Switzerland in March; China and South Korea in April; and Vancouver, Mexico City and Southern California in May.

While concentrating on canonical work with his orchestral appearances, he’s been stretching his repertory wings in recital, adding Arvo Pärt’s beautiful Fratres and Stravinsky’s Divertimento to his menu of Schubert, Brahms and Mozart. He also recently added a short encore piece (Harbour Reverie) by the contemporary Australian composer Carl Vine to his lists, and says he’s always on the lookout for compelling new material.

“I would never play a piece simply because I think I should play a contemporary piece. It’s not that I’m opposed to the idea at all, it’s just that I want to believe in it 100 percent,” Chen said. “I’m learning as well; as I play more and more repertoire, you develop a deeper sense of appreciation, you learn different styles, and you start to realize where a lot of modern-day composers get their inspiration from.”

Upcoming projects include performances of the Paganini First Concerto (in it’s original key of E-flat, with the violin tuned up a half-step), and a world-music collaboration with the young Israeli mandolinist Avi Avital (who will be in Miami for a concert March 2). They’ll start concertizing in June, and presenting music from China to reflect Chen’s background, and Eastern Europe, to reflect Avital’s.

“Then we’re going to tie it all together with Baroque music; Vivaldi, Bach, and sort of meld one piece into the next,” he said. “In all these types of music, traditional Chinese music and Eastern European and Baroque, they all used the violin and mandolin in one form or another … I want to get that connection with all these sounds.”

A mashup, in other words, fitting for a musician who’s so active in digital media. He has 1.75 million followers on SoundCloud, has produced a number of comedic music videos, and writes a blog about his touring life for RCS Rizzoli, the huge Italian publishing conglomerate. Newly single after a two-year relationship and “very much looking for the ladies,” Chen also is a fashion aficionado, and has a commercial affiliation with designer Giorgio Armani.

There, too, a mashup.

“Everyone wears clothes, and everyone has music in their lives. You can’t get away from it,” Chen said. “You can choose to learn more about fashion, just as you can choose to learn more about classical music. They’re both steeped in tradition, and nobody can tell you what you’re wearing is right or wrong, and nobody can tell you what you’re playing is right or wrong, but there’s definitely good taste and bad taste.”

Chen’s youth makes him a natural user of the kinds of technology that were new and experimental just the other day and now are an essential part of daily communication. But he also understands the way the classical music industry used to operate, and points out that there are few if any new concertgoers to be had that way.

“I’m trying to create a connection; that’s what we’re doing on stage. It’s much more difficult to do that when you just don’t talk, walk out on stage, play your thing, and then leave to go to the next city,” he said. “That’s hardly cultivating new audiences. You’re just retaining the audiences that are already coming to the concert hall who happen to like classical music, but you’re not doing anything as an artist to create new audiences.

“This is what has been going on, in my opinion, for the past few decades,” he said, adding that in an earlier day audiences might head down to a David Oistrakh concert because they had far fewer entertainment options. “And then suddenly, there’s been a change. And classical music didn’t catch on quickly enough. But I think it’s doing that now. And there are always new and exciting ways to do that.

“And I love the challenge of doing my part toward retaining new audiences for classical music,” he said.

Ray Chen and the Danish National Symphony Orchestra play at 8 p.m. Saturday at the Knight Concert Hall, Adrienne Arsht Center, Miami, and at 8 p.m. Sunday at the Kravis Center for the Performing Arts in West Palm Beach. Tickets for the Miami concert start at $50; call 305-949-6722 or visit www.arshtcenter.org; tickets in West Palm start at $30; call 561-832-7469 or visit www.kravis.org.