Sometimes not having made it pays off.

Just ask the five photographers currently showing their work at the Norton Museum of Art and competing for a $20,000 award.

They are the finalists of a new international photography competition the museum is hoping to turn into a new tradition called the Rudin Prize for Emerging Photographers, for which one of the requirements is to not have had a solo museum exhibition.

The participants represent four countries: Mexico, Argentina, Norway and Italy. Their group show runs through Dec. 9. One winner will be announced that same month.

Each artist’s work is presented separately in its own space, starting with Mexican photographer Eunice Adorno. Her shots, from the Flower Women series, are sensitive domestic portrayals of the intriguing German-speaking Mennonite women who today live in isolated communities in Nuevo Ideal, in the state of Durango, and La Onda, in Zacatecas, Mexico. Adorno captures them brushing their long thick copper hair and wearing floral dresses. In fact, flowers are everywhere from dresses to window curtains.

Los Vestidos de Elizabeth (Elizabeth’s Dresses, 2009) presents us with a line of silk-like night gowns or dresses hanging in a wardrobe or closet. All we see is a sleeve from each dress and some length. Each has a different color and a modest floral print.

One untitled shot depicts flower dresses drying out in the sun while hanging from a rope. As our eyes move from right to left, the dresses get smaller. The sunlight shines through them like a magical power that renovates them and makes them new again.

A photograph titled Maria Dos Veces Por Semana (Maria Twice a Week, 2010) features a mature woman looking straight at the camera. She wears a floral dress although in darker tones. Her long hair is parted in the middle and falls over her chest like two dense waterfalls. This symbol of healthy youth does not seem to go along with the wrinkles and bags under her eyes.

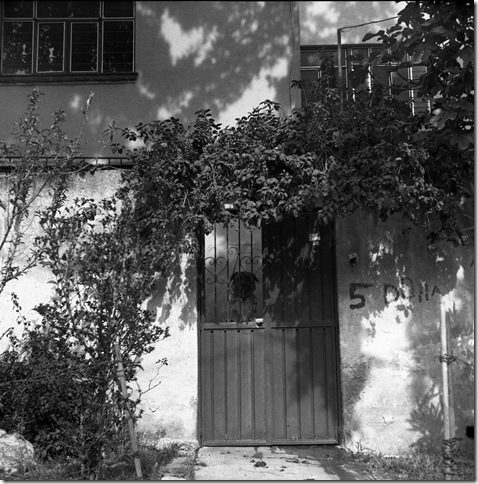

Depending on what direction you go, you may encounter the work of another Mexican photographer next. Gabriela Nin Solis’s black-and-white commentary on the impact construction has on natural areas and neighborhoods is not exactly revolutionary.

On display are about 24 photographs of an ongoing series she has named Gran Via, referring to the freeway that is being built in Mexico City. Most of the shots are untitled and paint a depressing picture. We do not get the suffering faces, the expressions of pain or the anger of a crowd. Instead we find balconies, disturbed fences, dust, dirt, doors and sidewalks of an old traditional pueblo that feels more like a ghost town.

No one is to be seen except for three dogs lying on a bare lot of land looking either too hungry or too tired to move.

It’s a series you can relate to if you have ever been against a zoning/building project threatening your view or your tranquility, or the character of your neighborhood. It is for the civic activist in all of us.

By contrast, the work of Norwegian-born photographer Bjørn Venø may appeal to our silly side. He is the wild card of the show. The three largest photographs, of eight on display, feature three male characters I can only describe as the king of the jungle, an adventurer on a raft and a decorated soldier.

They are Fatu Hiva (2011), Pacific Ocean (2012) and Texas (2011). The photos are from his MANN series, which explores male identity through self-portraiture. Here the king wears a primitive crown, the adventurer is depicted holding on to a rope ladder and the soldier sports his uniform. They would be the perfect model of vigorous masculinity except that something is not quite right with them.

As if to mess with this vision, Venø presents the bare-chested king licking his middle finger, the fisherman exposing his genitalia and the soldier drooling with a baby-face expression on. The three of them appear lost.

And so is the viewer probably at this point. In his statement Venø makes reference to “the struggle of seeking and the frustration of not finding anything of relevance.” This may well describe the way we feel looking at his work. Nothing really comes to mind. We feel like begging for a clue, some kind of hint. We get nothing. We are lost. Then again, a photograph does not necessarily need to speak to us right away, or even ever.

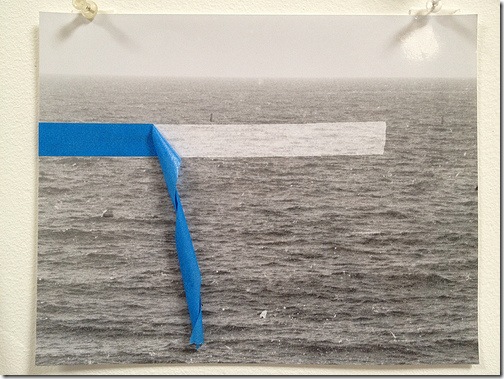

Following are 11 photos that come across as experiments in a white lab. Prints appear wrinkled, painted on, scrapped, unfinished. If you keep walking you will realize this is the work of Argentinean photographer Analia Saban. This portion of the show is entirely different in that there are no pretty shots. Saban pushes the photograph as a material to add to or remove from. In doing so, she grants a certain physicality and imperfection to an object we are used to perceive flat and judge in terms of color, light, composition, sharpness.

It is as if photography had decided to not take itself too seriously.

Take Folded Horizon (2012), a gelatin silver print featuring a calm sea. At some point, the artist folded the print in the middle leaving us with a pronounced mark that acts more like a vertical horizon and divides the image in two halves.

There is also Seascape with Blue Tape (2012), where a strip of tape is coming off on one side revealing how a photograph looks before it is actually finished. Rather than presenting us with polished refined shots Saban shares what we never get to see. That is why her pieces are not aesthetically pleasing. They do, however, change how we see photography.

If Saban is the most technical one of the group, consider Italian photographer Mauro D’Agati the most personal (aside from Mexican photographer Adorno). The 13 images on display resulted from his time spent following one member of an Italian family. D’Agati got to know their routines, interests and neighborhood. Looking at his photographs feels as if we were being introduced to the characters of a suspense film or a thriller. To be fair, there are also picturesque scenes of Italian architecture and city life.

Vico Santa Maria ad Agnone (2007) features an old woman bathed in an intense red light as if she was in a photographer’s dark room. She is wearing glasses. Her big eyes stare at a semi-open door where a dark blurry silhouette is captured coming or going.

On another shot, two men are having a casual meeting around the kitchen table. Cigarette in had they look to the person presumably doing the talking who is not shown. To me, it looks just like the scene of a movie where someone is about to burst in and start trouble.

D’Agati and the other four photographers were each selected by a well-established artist. This year the selecting panel included: John Baldessari, Graciela Iturbide, Susan Meiselas, Michal Rovner, and Yinka Shonibare. Five others will nominate new emerging talent every two years. The finalists will then present their work in a group show such as this one and the museum’s Photography Committee will select a winner.

The Rudin Prize award is named after the late New York City real estate developer Lewis Rudin, whose daughter, Beth Rudin DeWoody, is a member of the Photography Committee at the museum.