I think it’s safe to say the Kravis Regional Arts Concert Series, now celebrating its 40th year, has more visiting orchestras than any other venue in the world. There are seven this season, starting with the Russian State Symphony Orchestra on Wednesday evening with two Russian pieces and a Mozart piano concerto.

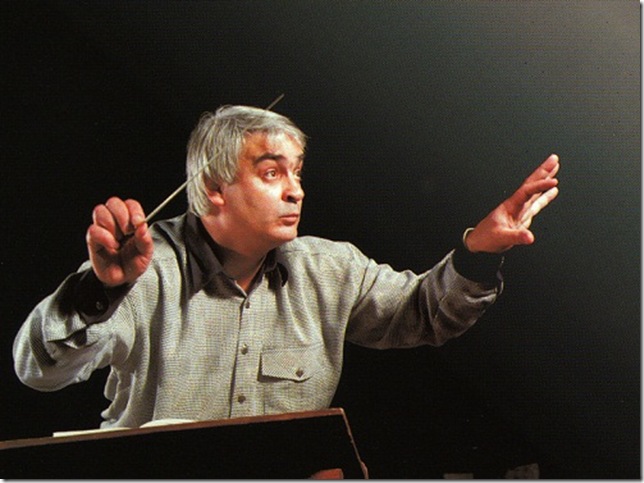

This 90-piece ensemble opened with Glinka’s overture to his opera, Ruslan and Lyudmila. Taking it at breakneck speed, one wondered if the disciplined violins would lose their bows in the process, but with the sweet central melody, panic was put to rest as we listened to their rapturous sound. Over ripe timpani at the end and cruder still trombone playing, the orchestra blasted out the closing last bars of a breathtaking performance. It was clear we were listening to an orchestra of merit, shaped since 1992 by chief conductor and artistic director Valery Polyansky.

Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 24 (in C minor, K. 491) followed, with the 62-year-old Vladimir Feltsman at the keyboard. Scored for larger-than-usual Mozart-sized orchestras, not a player left the stage, since the score retains oboes with clarinets and uses trumpets and drums, too. This is where conductor Polyansky showed his influence, keeping the sound controlled and lower in volume in the serious, businesslike opening; akin to what Mozart had in mind. Feltsman’s silvery silk entry matched the orchestra’s studied control. However, his exceptional playing was distracted by a nervous habit of using his free hand to conduct the music. This continued ad infinitum throughout the piece.

Feltsman has conducted orchestras, but these distracting hand gestures subtly undermine the role of maestro in charge at that moment. It might also have subconsciously echoed what was to come later in the program: the struggle Rachmaninov had between playing piano and composing. In the Alfred Schnittke cadenza of the first movement, I thought the pianist a bit heavy-handed. Frankly, it doesn’t fit at all nicely into Mozart’s style. A pianist of this caliber could have invented his own cadenza.

The major work of the evening, Rachmaninov’s Symphony No. 1 (in D minor, op. 13), took up the second half. In 1892, Rachmaninov graduated from the Moscow Conservatory with first prize in piano, and the gold medal, rarely given, for composition. After college he became very famous as a pianist but aspired to be a composer. Fueling this ambition, other composers at this time were turning out their fine symphonic works: Tchaikovsky’s Sixth, Brahms’s Fourth, Bruckner’s Eighth, Dvořák’s Ninth and Mahler’s First. So in 1895 he began work on his first symphony.

Underrehearsed by conductor Alexander Glazunov at its premiere in 1897, it was a disaster, sending Rachmaninoff into paroxysms of despair for three years. He recovered with help from a hypnotist and began composing his Second Piano Concerto. He abandoned the First Symphony score, leaving it in Russia in 1918 when he fled the Bolshevik Revolution. Rediscovered in 1944, a year after his death, the symphony was resurrected and got its second performance in 1945, and has become an audience favorite since then.

The symphony has an exciting opening. Oboe and clarinet duets break in with strong sweeping strings leading to a mighty all-out orchestral fugue. The strings almost “scream” at the close of a few demanding runs as rapturous type music trundles along like a magnificent musical freight train crossing the steppes of Russia. A melancholy flute theme is joined by the other winds, more Slavic music sounds, as the sweeping orchestral parts grow with hints of the piano concertos yet to come. Intensity of great quality builds to a familiar Russian theme and a quiet close.

The second movement (Allegro animato) begins quietly with much rumbling in the timpani, trumpet blasts and lovely glissandos from the strings. Luscious passages follow, strings accompanying plucking lower strings. The lyrical melodies are quite lovely to hear. One wonders how Rachmaninov arrived at this fascinating form of orchestration. The music has a haunting moody quality. The broad sweep of his lines are instantly recognizable. The movement ends with two plucked chords from the strings; this is incredibly lovely, nostalgic music.

The third movement (Larghetto) opens with flute and clarinet, followed by satisfying string chords. The flute now picks out future tunes given over to the violins. Dark tones from the trumpets in staccato form break in sustained by long chords from the second violins, cellos and double basses. A gushing melody in dreamlike Russian style winds its way through the orchestra. It has a lulling effect leading to a soft ending with six plucked string notes.

The final movement (Allegro con fuoco) starts with amazing fanfares; regal, stirring, even flesh-tingling stuff. Lovely oboes lead to symphonic music on a grand scale. Yearning romantic sounding strings give way to cheeky trumpets. The whole orchestra builds to a reflective passage. Declamation follows declamation. There was brilliant playing from all over the orchestra as each section makes its presence felt. A five-note tune gets resolved in a fantastic climax with big timpani sounds, blaring brass and a massively big ending.

What was Glazunov thinking by under rehearsing Rachmaninov’s First Symphony? Was he jealous, envious, or just lazy? Eight years Rachmaninov’s senior, he was on his way to writing nine symphonies himself, none of which are in the repertoire today. Conductor Alexander Gauk and the team that helped reconstruct Rachmaninov’s abandoned score in 1944 deserve recognition for saving this masterwork of symphonic invention.

For an encore, the Russian State Symphony performed another Russian work, “The Drayman’s Dance,” a polka from Dmitri Shostakovich’s 1931 ballet score The Bolt.