By Robert Croan

At the start of Seraphic Fire’s concert of English cathedral music Saturday night at Fort Lauderdale’s All Saints Episcopal Church, director Patrick Dupré Quigley spoke to the audience, explaining that there would be 75 minutes of uninterrupted music, and asking that the listeners not look at the printed program during that time.

“Just let the music wash over you,” he suggested. The details and texts might be studied afterwards as a kind of homework assignment.

Spoiler note: I perused the program while the concert was in progress, partly in order to write a properly informed review, but also because I have a curiosity that makes me want to know what I’m listening to at any given moment.

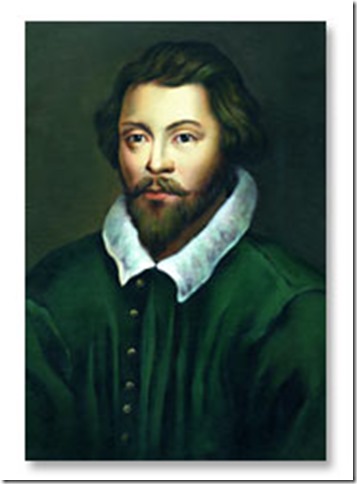

Nonetheless, this is typical of the innovative and inventive programming that Quigley has made integral to this unique and valuable series. The present program, closing the 2015-16 season, featured the music of William Byrd (c. 1539-1623), but included sacred music by Byrd’s mentor Thomas Tallis, as well as his younger contemporaries, Peter Philips and Thomas Morley.

Presented approximately in chronological order, the 19 selections comprised a compendium of the British monarchy in the 16th century, along with a journey through pre-Reformation English church music, early Protestant reforms, post-Reformation Catholic service music (often secret because it was deemed seditious) and the middle road coexistence espoused by Queen Elizabeth I.

The program began with a Sarum chant — associated with the rites celebrated in Salisbury Cathedral in the 11th century. Members of the 13-voice a cappella choir processed while singing from the back of the church, which gave the music a super-resonant acoustic quite different from that of the singers’ normal position in the transept. There followed four Latin motets and an English anthem by Tallis, the thorniest, most cerebral music of the evening.

In general, the Catholic works were more complex than the Protestant, the newer music more euphonious and melodic than the old. The introduction of Byrd’s music, after 20 or so minutes of Tallis, juxtaposed two of his Protestant anthems from the time of Edward I with Latin motets dating from Mary I’s Catholic Restoration. Of the latter, the Seraphic singers brought out the intricate rhythms of “Emendemus in melius,” then gave a welcome zing to a surprisingly lively setting of “Tu es Petrus.”

Ensemble was superb throughout. Attacks and cutoffs were razor-sharp, accents strongly defined, inner textures clear and transparent. The basses throughout were impressively reverberant, the overall effect marred only by one strident soprano whose prominent high lines were not consistently in tune.

Byrd was born Protestant but became a Catholic later in life, treading a fine line of following his own tenets and maintaining the favor of the very tolerant queen. His Elizabethan-period works were the most varied and interesting. At this point, Latin was not excluded from the Protestant service, and there evolved a fascinating amalgamation of styles that none of Byrd’s contemporaries achieved in quite the same way.

Among the English-language works from Elizabeth’s reign, the first, “O Lord, make thy servant Elizabeth … rejoice,” was remarkable for the clarity of the words and the ringing counterpoint of its Amen. “O that most rare breast” was notable for a particularly beautiful text honoring poet and soldier Sir Philip Sidney, who died at the age of 31, after being wounded in battle (for the Protestant cause) in 1586. On the happier side, “Sing joyfully,” with vocal lines suggesting the sounds of trumpets, was vibrantly sung, with a spirit of fun. Morley’s “I am the resurrection” (with a middle section, “I know that my redeemer liveth”) provided an affable interlude in Italian madrigal style

“Laudibus in sanctis” gave the singers opportunities to produce a range of colors that was almost orchestral. Byrd wrote three setting of the Mass – one each for three voices, four voices and five voices. Quigley framed his final segment with the opening and closing movements of the Mass for Four Voices, the choir chewing deliciously at the sophisticated counterpoint of the final “Agnus Dei.”