By Robert Croan

If you’ve seen the Coen Brothers’ O Brother, Where Art Thou, which has become a cult movie since its release in 2001, you’d have recognized several of the Appalachian hymns included in Seraphic Fire’s concert of The American Spiritual, performed in five South Florida venues Jan. 12-17. Artistic Director Patrick Dupré Quigley labeled the concert “an expression of pure joy,” but as the event proved, American spirituals come in all sizes, shapes and forms: happy and sad, white and black, short and long, folksy and operatic.

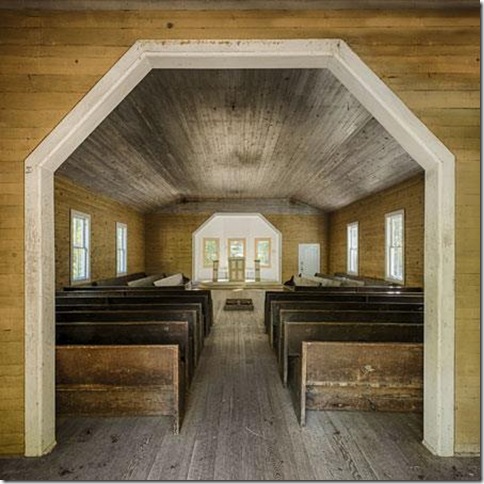

The 90-minute concert Saturday at All Saints Episcopal Church in Fort Lauderdale opened with the simple Appalachian folk song, “In a Land Where We’ll Never Grow Old” — attributed variously to James C. Moore in 1914 and William Pond in 1879 — and closed with encores that included Julia Ward Howe’s “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” in a sensational contemporary jazz-gospel rendition by bass Charles Evans.

Seraphic Fire is a 13-member choir led by Quigley, who also sings, composes and accompanies on piano, as required by the repertory. The present concert was mostly a cappella but several pieces included piano, and at one or two points, string bass as well. Individual numbers were not listed in the printed program. Quigley announced each work from the stage, giving an interesting and informative history of the spiritual as he went along.

Quigley explained at the start the two contrasting, co-existing strains of the American spiritual: white spirituals — notably those of Appalachia — and the African-American songs rooted in slavery, subsequently shaped by the enormous prejudice against blacks that followed abolition. The conductor also pointed out that while the original melodies and words of American spirituals may have diverse origins — European, American, African — the arrangements we hear now are actually unique compositions of professional composers.

Early on, Scottish hymnals provided the inspiration. In the 19th century, Mendelssohn was a frequent model, while post-Civil War composers who took up the music of freed slaves strived to emulate the bel canto opera style of Donizetti and Bellini: thus: the sustained descant melodies that typically soar above the choir. In the traditional vein, William Levi Dawson’s settings of “There Is a Balm in Gilead” and “Ev’ry Time I Feel the Spirit” show expert craftsmanship. In contemporary culture, today’s jazz and gospel singers incorporate those elements in their renditions of these songs.

The Appalachian songs had a noble quietude that sometimes gave way to more overt emotional expression. Many began with a single voice, gradually expanding into two-, three- or four-part polyphony. Quigley seemed to prefer an unblended sound among the singers, in which individual voices stand out rather than merge into the ensemble. For the most part this added to the folksiness and informality. Some singers in the group are better than others, however, and when an individual’s sound was edgy or out of tune, the fault was brought into higher relief. Whether the sound was rough or blended, however, there was a unanimity of purpose and precision of attacks and cutoffs that never failed.

A highlight of the Appalachian group was the lilting “Keep on the Sunny Side,” performed with piano and string bass — a revival hit popularized by a 1928 recording by the Carter Family folksingers. “In the Sweet Bye and Bye,” with Sara Guttenberg an unsteady soloist, fared less well.

Among the members who came off best as soloists were countertenor Reginald Mobley and bass Evans, the only African-Americans in the ensemble. They were quite delightful together in John Work’s lively slave song, “Little Black Train is A-Comin’,” effectively followed by that composer’s quieter “This Little Light of Mine,” in which mezzo-soprano Amanda Crider provided lovely solo moments. Mobley was especially appealing in “Over My Head I Hear Music,” and Evans gave a touching rendition of “Were You There When They Crucified my Lord.”

These were just a few of the evening’s highlights. Soprano Kathryn Mueller’s strong soprano dominated Roland M. Carter’s “You Must Have That True Religion,” while Mela Dailey’s lovely sound enhanced Moses Hogan’s “Great Day.” In each case the supporting vocalists gave shape and feeling to the unique character of each song.

The pre-encore part of the concert ended with Quigley’s own arrangement of “Steal Away,” which happens to be the title (and the opening number) of Seraphic Fire’s latest CD — not surprisingly, a collection of American spirituals.