By Dennis D. Rooney

Seraphic Fire, now in its 16th season, has performed to growing acclaim in its South Florida home. Its March 18 program, titled Liebeslieder Waltzes, was devoted to vocal music designed primarily for domestic entertainment.

Accomplished amateur singers and players in the 19th century would gather to make music at a time when there were no recordings. If you wanted to hear music at home, you had to make it yourself. Hausmusik was the genre and composers kept musical amateurs steadily supplied with works that invited convivial performance for their own benefit and anyone else who might be on hand.

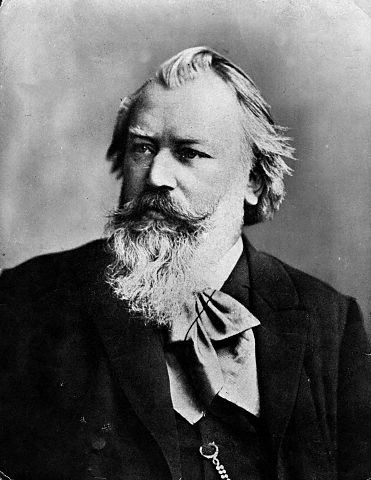

Because of an unfortunate late arrival, I missed the first five items on the program. The portion I heard began with Franz Schubert’s “Nachthelle” (D. 892); Felix Mendelssohn’s “Die Nachtigall” (Op. 59, No. 4); Robert Schumann’s “In der Nacht” (the fourth of his Spanisches Liederspiel, Op. 74); “In Stiller Nacht”, one of the Deutsches Volkslieder (WoO33) published by Johannes Brahms in 1894; and that composer’s partsong “O schöne Nacht.” The ninth of Schumann’s Spanisches Liederspiel, “Ich bin geliebt,” concluded the group.

“Nachthelle,” one of three partsongs that Schubert wrote in 1826 to texts by Seidl, describes the increasing brightness of enlightenment felt by the poet. The song climbs steadily until the solo tenor reaches a high B-flat. The male voices were in front for this selection but the Mendelssohn, for a capella mixed voices, was sung from the back of the chancel. The soprano and tenor soloist in Schumann’s “In der Nacht” sang with pianist Scott Allen Jarrett, who was also the conductor. The following Brahms songs had mixed voices singing a capella. Schumann’s “Ich bin geliebt” was sung with piano and concluded the sequence.

The remainder of the program presented the Liebeslieder Walzer, Op. 56, which Brahms composed in the summer of 1869. The texts of the 18 choral songs come from Polydora, a collection of folk songs and love poems by Georg Friedrich Daumer (1800-1875) (who also wrote the text of “O schöne Nacht”). They may have been inspired by the composer’s admiration of Schubert’s Ländler. The other obvious influence is Johann Strauss Jr., the “Waltz King.”

The original score is marked ad libitum, which allows for performance by different ensemble sizes. The voices are accompanied by piano four hands, which further intensifies the domesticity of the work, that configuration being the usual piano transcription format for orchestral and chamber music. All 18 songs are short and express various thoughts on the nature of love. They became immensely popular and the composer profited handsomely.

The members of Seraphic Fire are ensemble specialists, agile vocalists with keen accuracy of intonation who can respond quickly to rapid shifts of tempo and texture. But their singing is rather tonally austere, as I heard it, better suited to Dufay, Josquin or Schütz than Schubert, Mendelssohn, Schumann and Brahms. Part of what I heard may have been due to the venue (All Saints Episcopal Church in Fort Lauderdale), which I visited for the first time, or my location within it, but I kept hoping for more vocal warmth and a better foundation from the lower voices.

In the Brahms Liebeslieder, pianists Jarrett and Anna Fateeva were often lacking in both vital impulse and a sense of gaiety so essential to the set’s success.