Back in the early days of Seraphic Fire, the Miami concert choir took on the challenge of all six motets by J.S. Bach.

The performance I saw 12 years ago was very fine, but effortful: The difficulty of the music took its toll on the singers, and it was noticeable by the end of the concert. The group has done one or another of the motets individually since then, but this weekend it mounted the full cycle again, and this time with brilliant results.

Saturday night at All Saints Episcopal Church in Fort Lauderdale, the 15th-anniversary edition of Seraphic Fire, now expanded for these concerts to 19 singers accompanied by organ, cello and theorbo, gave a powerful, resonant reading of these hugely challenging masterworks, and in so doing achieved one of the milestones founder Patrick Dupré Quigley intended for his group.

The concert was divided into two halves with an intermission, a wise choice given the length of the program and the need to rest voices. Longtime audiences of this group are used to Quigley’s forceful, energetic, swift tempi, and there was no shortage of those Saturday night. But in the very first motet, Lobet den Herrn, alle Heiden (BWV 230), the pace was leisurely, the voices full and warm. In the “Alleluja” section, Quigley hammered home the octave jumps in the bass and continuo for a joyful effect that didn’t detract from the overall smoothness of this reading.

Komm, Jesu, Komm (BWV 229), one of the most affecting of these six motets, began with beautiful restraint and a sober unfolding of melodic lines between the two choirs, and then to a full-throated exploration of the remainder of the opening section. In the closing chorale, “Drum schliess ich mich in deine Hände,” the choir kept the volume at forte throughout, which detracted from Paul Thymich’s text somewhat, which is about a dying person’s resolve to leave their remaining moments in the hands of God and trust in eternal salvation. Some more dynamic contrast would have been welcome, beautifully sung as the motet was.

The first half closed with a vigorous and superbly sung Singet dem Herr nein neues Lied (BWV 225), a contrapuntal tour de force that was wonderfully realized. In the outer sections, the music sounded radiant and remarkable, with its multiple lines seamlessly ebbing and flowing, the voices of these gifted singers ringing off the walls of All Saints and making manifest the Psalmist’s hymn of praise. For the chorale section, Quigley used a quartet against the responding choir; led by soprano Margot Rood, this provided a much lighter texture, ably performed, before the full forces returned for the closing section, which again proved astonishing in its most fundamental way: To think these are simply human throats making these immense and complicated sounds is a cause for wonder.

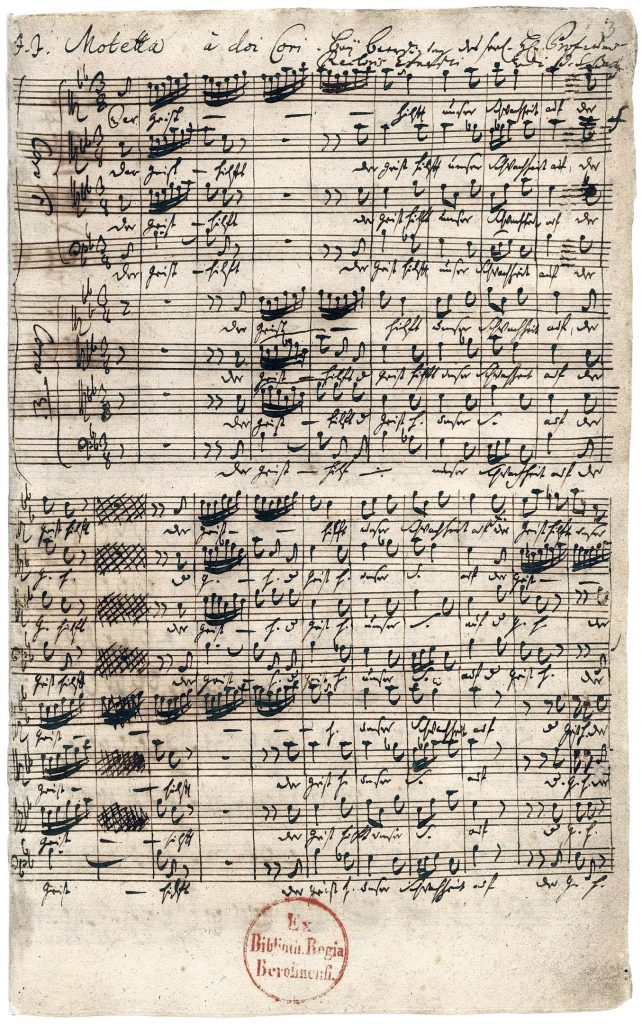

The second half opened with Der Geist hilft unsrer Schwachheit auf (BWV 226), sung at a bracing tempo in the first section, and only slightly less so in the second. In the closing chorale, “Du heilige Brunst, süsser Trost,” the singers added some warmth, wrapping the motet up nicely. As in Singet dem Herrn, the individual command by each singer of these complex textures was gratifyingly accurate, so that at it no time did it sound busy or indistinct; rather, it was strong and formidable.

The fifth motet of the night, Fürchte dich nicht, ich bin bei dir (BWV 228), is, as Quigley noted in his remarks to the audience, one of the most difficult of the six for its harmonic difficulty. In this, indeed, at least in the final section, it harkens back to the extravagant experiments of late Renaissance composers such as Carlo Gesualdo, an effect heightened Saturday night by the sound of John Lenti’s theorbo. Quigley and the choir sang this motet with seeming ease and a pleasant lift, but there were notable signs of fatigue at the beginning, with some less-than-secure singing before matters straightened out.

The final motet, Jesu, meine Freude (BWV 227), is difficult for its subtlety, shifts of mood, and multiple singing challenges. Quigley and the choir approached it in a more matter-of-fact way than that, chugging vigorously through some of Bach’s treatments of the chorale on which it is based, and pulling back in others. Here, too, some more nuance and contrast would have underlined the text better, and made for more variety.

But there was no gainsaying the skill with which these singers handled this music, or of the three continuo players who supported them — Lenti, along with organist Justin Blackwell and cellist Guy Fishman. And at its best Saturday, the 19 vocalists in this iteration of Seraphic Fire sang with a beauty of blend and tone that suggested this particular combination of singers may be the lineup Quigley should return to as often as he can. They helped him achieve his Bachian landmark, after all, and in so doing revived a sextet of early 18th-century masterpieces for an eager and interested audience.