By Robert Croan

Performing in three South Florida venues on successive evenings last weekend, Miami-based chamber choir Seraphic Fire joined with New York instrumental ensemble The Sebastians in a first-rate tribute to composer Franz Joseph Haydn: two of his late choral works, with a delightful middle-period symphony felicitously sandwiched in between.

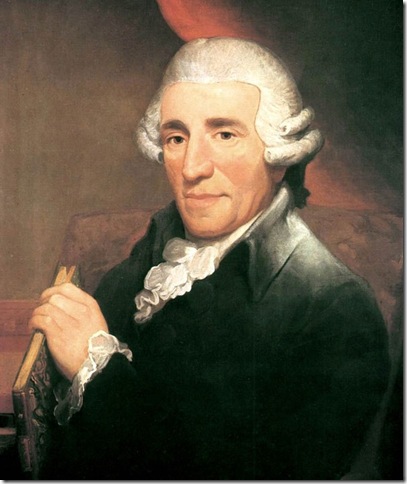

To most classical music lovers, Haydn is the father of the symphony and of the modern string quartet. He is less well-known for his abundant vocal output, which included, among other works, 15 operas, three oratorios and 14 settings of the Latin mass. The six masses he composed late in life at the court of the Esterhazy family (his lifelong patron) are some of his most important works. Haydn biographer H.C. Robbins Landon referred to the so-called “Lord Nelson” Mass, the featured work on Seraphic Fire’s program, as “arguably Haydn’s greatest single composition.”

It is a work of considerable gravitas, although the popular epithet is probably spurious. Once thought to have been inspired by Admiral Horatio Nelson’s victory over Napoleon in the Battle of the Nile, the work had been completed by the time of that famous event, Aug. 1-3, 1798. Haydn’s own subtitle was “Missa in Angustiis” (mass in time of distress) reflecting the troubled state of the world (it was feared that Napoleon might gain control of the Austro-Hungarian Empire). The “Lord Nelson” attribution was affixed after the admiral visited Esterhazy Palace in 1800, and this mass was performed there in his honor.

By Haydn’s time, concert masses in elaborate operatic style used full a symphony orchestra and were not necessarily intended for liturgical use. The “Lord Nelson” Mass requires vocal soloists and choral singers of the highest caliber, along with an instrumental contingent of similar abilities. Seraphic Fire and The Sebastians, under the direction of Seraphic’s leader Patrick Dupré Quigley — heard Saturday in Fort Lauderdale’s All Saints Episcopal Church — were historically accurate without being overtly scholarly. Musical values superseded intellectual details. Expression and communication came first.

The 20-voice choir and the 24-piece orchestra of period instruments — proportions appropriate to Haydn’s time — lent clarity of line and harmony, with an intimate, personal quality that pervaded the entire event. It seemed that the performers were singing and playing for each audience member as an individual. To be sure, such an approach exposed some flaws along the way — mostly in pitch, which the ensemble remedied by tuning more frequently between movements than would be necessary for an orchestra of modern instruments. But the gain in communication far outweighed any concerns over incidental flaws, and the instrumentals’ techniques, as manifested in solo playing and team precision, were exemplary.

This was evident in the piece that opened the program, a joyous, brief “Te Deum” composed for the Empress Maria Theresa, delivered with musical accuracy and infectious exuberance. Quigley remarked at the end of the work that this would be the last happy piece of the evening. And while it’s true that the “Lord Nelson” Mass is profound and serious, it is not without its own moments of hope and elation.

In the “Kyrie,” the soprano soloist exhorts for mercy in dramatic flights of coloratura worthy of Mozart’s Queen of the Night. The “Gloria” oozes with optimism, while the fugal counterpoint of “In Gloria Dei Patris” seemed to lend assurance in Seraphic Fire’s solid, positive rendition. The solo singers were chorus members unspecified in the printed program, and all four (soprano Kathryn Mueller, mezzo-soprano Margaret Lias, tenor Steven Soph and bass-baritone James Bass) were excellent — notably the bright-toned Mueller, and the resonant Bass, who gave a moving account of the rather grand pseudo-aria, “Qui tollis.”

There were instrumental rewards, too. Haydn’s Symphony No. 45 is called the “Farewell” Symphony because the court musicians — who in those days were treated somewhat as indentured servants — were being held at the Esterhazy summer palace for an extraordinary length of time, longing to be released to return to their families. Haydn, with his pungent sense of musical humor, added a coda to the final movement, in which the players, singly or in pairs, gradually leave their music stands and walk offstage, until only two violinists are left for the concluding measures.

That section always gets laughs, but for the opening movement Haydn called on the “Storm and Stress” style in vogue during the 1770s, to invoke the anxiety felt by the palace players. Conductor Quigley brought out the contrasts and manipulations of themes and harmonies that eventually became the defining formal element of the symphony, “sonata form.” The Sebastians took every opportunity to shine with their virtuosity on period instruments that present challenges such as gut strings that vibrate differently than modern steel ones, unvalved horns and trumpets controlled entirely by the lips. Undaunted, the performers reveled in these and other challenges, emerging not merely unscathed but eminently victorious.