The Canadian pianist Marika Bournaki made something of a splash back in 2012 with the release of a documentary about eight years of her young musical life as an emerging classical pianist.

I am Not a Rock Star was an interesting look at the life of a talented child, and later woman, from the suburbs of Montreal who goes to Juilliard to pursue her dream of becoming a concert pianist. She comes off in the film as smart, funny and determined, and we hear substantial examples of her keyboard skills.

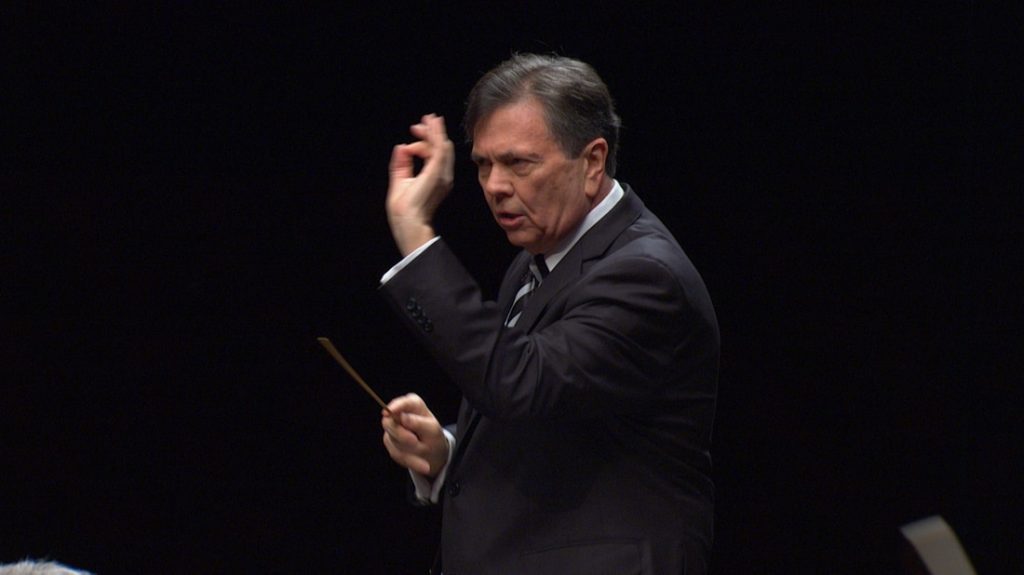

She made an appearance around that time at the Festival of the Arts Boca, and it was good to see that she was back in town Sunday, this time for a reading of the Piano Concerto No. 20 (in D minor, K. 466) of Mozart with The Symphonia Boca Raton for the chamber orchestra’s opening concert of its new season. At the helm was Gerard Schwarz, the eminent and emeritus conductor of the Seattle Symphony, whose cellist son, Julian, a two-time Symphonia guest, is Bournaki’s chamber music partner in a cello-piano duo and a piano trio.

And Bournaki proved to be an exemplary soloist, a player of clarity and impressive technique whose Mozart was elegant and sensitive. Dramatic, too, as required in the outer movements and the Beethoven cadenzas, in which she shaped the mini-arcs of those somewhat extravagant commentaries with a sure hand. Her touch in the familiar second movement was light and unsentimental without being shallow, and the tempo was not overly slow.

The Symphonia and the elder Schwarz accompanied her well, and by the end of the first movement there was a distinct feeling of commitment and shared adventure across ensemble and soloist. This version of the Symphonia had a slightly smaller string complement than what would have been ideal, and that gave the music a heavier wind and brass feel than concertgoers might normally encounter. Still, it was a satisfying and effective rendition of this great concerto, and drew a vociferous response from the modest audience at the Roberts Theater on the campus of Boca’s St. Andrew’s School.

Bournaki responded to the standing ovation acclaim she got with an encore: the Andante Spianato of Chopin. Her left-hand spinning wheel was strong and steady and stayed well under the melody, and she played the secondary answering theme with real tenderness, rounding out a lovely performance.

In addition to another Mozart work, the Linz Symphony (No. 36 in C, K. 425), which closed Sunday’s concert, there were two works by leading 20th-century American composers, Walter Piston and Elliott Carter. Schwarz is probably the leading champion of Piston’s music working today, having recorded substantial amounts of his symphonic output with the Seattle Symphony. The Sinfonietta, which dates from 1941, is a good example of this overlooked American composer’s mastery of his craft and his ability to write an accessible piece of contemporary music at a time when much cutting-edge creation had gone in a different direction.

With The Symphonia, Schwarz’s tempos were a little slower and more cautious than his recordings, especially in the two vigorous outer movements, but it was still an admirable performance overall. The martial secondary theme in the first movement had bite and wit, and the strings set a good mood of mystery in the opening bars. The hint of Beethoven’s Seventh at the opening (and closing) of the second movement was precisely brought out, and the highly emotional rhetoric of most of the movement was large and vivid if not epic. And Schwarz and the Symphonia did a commendable job with the finale, which while pokier than it should have been, moved along with sparkle and high spirits.

Elliott Carter’s Elegy, a work from 1943 originally for cello and piano, was rescored that year by the composer for string orchestra, and it was this version that opened the second half of the concert. Carter, of course, was celebrated for his later music, compositions of uncompromising rhythmic complexity and atonality, but it is this gentle piece, which has much more in common with his contemporaries Samuel Barber and David Diamond, that is perhaps best-known. The strings played it with skill and subdued emotion, and Schwarz directed the final accented chord entrances with a distinctive hand gesture that helped the audience follow the architecture of Carter’s coda.

The Mozart symphony that closed the concert is more modestly scored than the great 39-41 sequence, but it is scarcely less brilliant and deserves more attention overall. Signs of inadequate rehearsal were evident here and there, particularly in the third movement Menuetto, where the brass entrances were not together and far out of balance with the rest of the orchestra. Here, too, tempos were more deliberate in the first and last movements to accommodate the realities of short practice time with busy freelancers.

But this reading of the Linz Symphony showed Boca audiences that Schwarz is a fine Mozartean, as indeed he has demonstrated with this orchestra in years past. His Mozart appeals because he is able to match the abundance of the composer’s invention with an interpretation that evokes the joy with which he most likely wrote it; you get, as a listener, a sense of 18th-century check-this-out that keeps this 235-year-old music fresh.

In general, ensemble was good and the symphony came off well, with cheerful sturdiness in the opening movement, operatic songfulness in the Poco Adagio, and exuberance in the finale (though bigger string numbers would have made the climbing sixteenths in the final pages more exciting). This was a strong and well-designed concert, and for the first time I can remember in this group’s history, there were no verbal program notes or Symphonia housekeeping announcements after the intermission. Both suggest a new seriousness for the group that is most encouraging.