Fortunately for all concerned, Stephen Sondheim’s Look, I Made a Hat is not a treatise on the art of millinery.

Instead, it is the sequel to Finishing the Hat, the pre-eminent American theater composer-lyricist’s compilation and consideration of his career, divided into two volumes and filled with nuggets of insight. Or, as he prefers to put it in his subtitle, “Collected Lyrics (1981-2011) with Attendant Comments, Amplifications, Dogmas, Harangues, Digressions, Anecdotes and Miscellany.” Indeed.

As Sondheim’s legions of fans — of which I unabashedly count myself — could explain to the puzzled, Finishing the Hat is a central musical number in his 1985 Pulitzer Prize winner, Sunday in the Park with George, a statement in song by post-impressionist pointillist painter George Seurat of his obsessive creative process. Painstakingly, he applies dots of paint to canvas until the eye perceives it as a chapeau, Hence, the song’s concluding line and the book sequel’s title, “Look, I made a hat.”

Sondheim divides his career more for ease of lifting the individual volumes instead of inducing hernias with one heavy tome. But there was a distinct tonal shift for him in 1981, caused primarily by the extended suspension of his collaboration with director Harold Prince (Company, Follies, Sweeney Todd and the contentious, quick-folding Merrily We Roll Along) and his embarking on a very different professional partnership with librettist-director James Lapine (Sunday in the Park…, Into the Woods, Passion).

True, Sondheim has more shows to his credit in the first “half” of his career (the briefer 1954-1981), so he pads the second volume — still fascinating, mind you — with such miscellany as his movie work (a brothel madam’s solo from The Seven Percent Solution, the score for Dick Tracy, which netted him an Oscar for the languorous Sooner or Later, two barely used numbers for The Birdcage and several intricately conceived songs for the lamentably unproduced Singing Out Loud, which was to be directed by Rob Reiner).

Other included footnotes to his career include Sondheim’s work for television, the most major of which is the hourlong musical Evening Primrose, the tale of a man who escapes from the world to a new life inside a department store. From it comes such cabaret fixtures as I Remember and Take Me to the World. Hailing from 1966, it is out of place chronologically, but since it did not make the cut into the first volume, we will take it — and Sondheim’s recollections of the program’s genesis — any way we can get them.

Other included footnotes to his career include Sondheim’s work for television, the most major of which is the hourlong musical Evening Primrose, the tale of a man who escapes from the world to a new life inside a department store. From it comes such cabaret fixtures as I Remember and Take Me to the World. Hailing from 1966, it is out of place chronologically, but since it did not make the cut into the first volume, we will take it — and Sondheim’s recollections of the program’s genesis — any way we can get them.

It would be sufficient if Sondheim had merely collected and published his lyrics, the final scores plus the various interim versions and numbers deleted along the precarious road to Broadway. But as he did previously, he pauses, often mid-song, to emphasize a creative impulse, explain a word choice, underline a hair-splitting intention or otherwise muse on recalled anguish as he wrote. The result is again a highly personal tutorial on the history of the musical theater of the past almost 60 years.

But before the reader can get to class, there are the inside covers of the book, which contain Sondheim’s three deceptively simple guiding principles:

Less Is More

Content Dictates Form

God Is in the Details

As we will learn, had he only followed those three tenets more carefully on his most recent narrative musical, Road Show (and its precursors, Wise Guys, Gold! and Bounce), he could have saved himself a lot of grief and certainly some of the 14 years of his life going through three directors, three out-of-town tryouts and six actors in the two leading roles for a show — about the Mizner brothers of Palm Beach — that never opened on Broadway. Or at least, hasn’t yet.

One needs to dive headfirst into the text notes amid the lyrics, but here are a choice nuggets (of trivia) to be found there:

* Once per show, Sondheim says he cries at his own work “and Animal Planet, often.”

* Into the Woods, a musical based on scrambling several Grimm fairy tales and considering the consequences of “happily ever after,” began instead with an idea of scrambling television shows.

* The song I Guess This Is Goodbye that Jack sings to his pet cow in Into the Woods is, according to Sondheim, the only song he has written without any rhyme at all.

* In the midst of the discussion of Assassins, he writes, “Audacious is an inch away from smart ass, as Anyone Can Whistle proved.” Doctoral theses have been based on less.

* The show that Sondheim says comes the closest to his expectations for it is … Assassins.

* Sondheim almost wrote a musical of Sunset Boulevard, until the film’s writer-director Billy Wilder casually mentioned that the subject matter required kit to be an opera (an art form Sondheim never warmed to). Then, he adds, “someone eventually wrote it” and Wilder was proven right.

* When Sondheim and John Weidman wrote Road Show/Bounce/Gold!/etc., it saved him from dealing with Weidman’s idea of a musical about the League of Nations. Oy.

Also sprinkled throughout the book are sidebar essays on such topics as reviewers (he is dismissive, but reasonably dispassionately so), awards (he finds them fairly useless unless they come attached to cash) and revivals (most notably a revelatory production of Passion that changed the show’s focus because of one startling performance). And while he promises early on some comments about other lyricists that should “generate enough irritation to go around” — as certain opinions in the first volume did — either he is in a much more mellow mood this time or he is withholding his more disdainful views.

Also sprinkled throughout the book are sidebar essays on such topics as reviewers (he is dismissive, but reasonably dispassionately so), awards (he finds them fairly useless unless they come attached to cash) and revivals (most notably a revelatory production of Passion that changed the show’s focus because of one startling performance). And while he promises early on some comments about other lyricists that should “generate enough irritation to go around” — as certain opinions in the first volume did — either he is in a much more mellow mood this time or he is withholding his more disdainful views.

As much as I treasure the glimpse into Sondheim’s mind that these two books represent, they also signify to me a large amount of time that might have been better spent writing another musical.

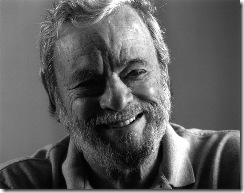

In Look, I Made a Hat, he ruminates over whether he is running out of inventive steam at the age of 80-plus. In his epilogue, he commends to his readers with a creative impulse Phyllis McGinley’s poem, Love Note to a Playwright, calling it “as important a piece of advice as you’ll ever get,” adding “if I’d listened to it the way I think every artist should, I wouldn’t have written these books, I’d have written a couple of musicals instead.”

At least his final words here are the heartening, “Time to start another hat.”

Look, I Made a Hat, by Stephen Sondheim. Knopf, 453 pages, $45.