By Robert Croan

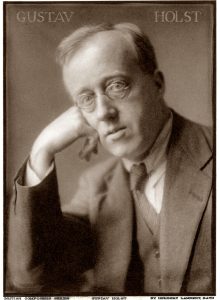

Gustav Holst’s The Planets is one of the great orchestral showcases, and one of the most difficult for any orchestra to carry off.

It’s a mammoth hourlong work for large orchestra, usually of close to 100 players, so it was remarkable to see it on the docket for the opening concert of Fort Lauderdale’s Symphony of the Americas on Oct. 6 in Broward center’s intimate and genial Amaturo Theatre. Even more remarkable was the assurance and aplomb with which the 60-member ensemble, under conductor Pablo Mielgo, carried off this daunting assignment.

There are many new names and faces, especially among the first-desk players, since the Spanish maestro took over as SOTA’s artistic and music director in 2020. Precision of attack, right-on intonation, and virtuosity in the abundant solo turns characterized Mielgo’s skilled baton technique and authoritative leadership. But there was more than technical accomplishment. Each movement of this bombastic, often intractable piece, had a sharply defined character that came through with an emotional core.

Holst’s score is not particularly profound. It comes at the listener in an in-your-face way, reminiscent of 1930s and ‘40s movie scores by Erich Korngold and Max Steiner. Think John Williams on steroids. Except that it’s the other way around: Holst’s Planets had its first performance in London in September 1918.

The composer was not much interested in the astronomy of the solar system. Each of the seven movements conveys a mood determined by the astrological connotations and mythic descriptions of the Roman gods for whom each planet was named. Omitting Earth, Holst evoked the first three planets in reverse distance from the Sun, then the four ice giants from Jupiter to Neptune. (Pluto had not yet been discovered.)

Holst started his orchestral suite with “Mars, the Bringer of War,” a movement he was quoted as having composed to bring out the “stupidity” of war. It’s a rhythmically askew march in 5/4 time, choleric and belligerent from the start, and Mielgo made a strong statement, clearly accented with the intentional irregularities.

“Venus, the Bringer of Peace,” which follows, opened with some admirable horn playing from principal horn Matthew Marshall, followed by a sweet-toned delivery of the music meant to depict the goddess herself by concertmaster Scott Flavin. The third movement, “Mercury, the Winged messenger,” is the scherzo of the collection. Brief and fleeting in its Mendelssonian lightness, the music demands absolute precision and clarity, which for the most part, was achieved.

As for the more daunting outer planets, “Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity” rollicked with Falstaffian bounce and ineptitude, often expressed in humorous outbursts from the lower brasses, as well as the bouncy folk-dance beat; while the rendition of “Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age” properly maintained an intentional lugubriousness.

In the real solar system, it has since been learned that Uranus is a static world with few events, while Neptune is a sea of volcanic turmoil. (I learned this from watching Nova on PBS.) Holst, however, took the reverse outlook. His musical Uranus is heavy on the brass and timpani, lots of fun for listeners and players alike — or, at least that’s how it came across here. And the symphonic Neptune brings the work to soft and dreamy wind-up, eliciting some particularly lovely sounds from harpists Diana Rada and Marti Moreland.

The first half of the concert, before intermission, opened with Faure’s Pavane, during which the players seemed still to be finding their bearings. They were in form, however, for a lively and songful rendition of Smetana’s The Moldau, which on the eve of Oct. 7, took on special timeliness for its main melody, the basis for the national anthem of Israel, “Hatikvah.”