There’s something to be said for the sort of tradition that manages to intrigue upon each arrival, and when it does so in the guises of filigreed robots, childhood make-believe, or the lipsticked grit of a Bayou starlet — all the better, I say.

So unfolds this year’s southXeast: Contemporary Southeastern Art at Florida Atlantic University’s galleries, which presents the efforts of 13 Southeastern artists, including three of Florida’s own (Carl Knickerbocker, Clive King, and Beatriz Monteavaro). Housed in both the university’s Schmidt and Ritter galleries, the show strips the term “regional” of its aw-shucks connotations and addresses the texture that may be found when playfulness is executed with an eye towards the hallucinatory, whether rooted in the real or in the wholly imagined.

Let’s be clear: this assembly of works is not reinventing the aesthetics of identity. The collage, installation, video, drawing, and paintings found here utilize recognizable tropes to address gender, or to lift the banal into loftier realms of contemplation. Pop-culture personalities such as Elvis, or the racially charged appropriation of a “Sambo” character, for example, are once again introduced as metaphors for desire or perception.

But our recognition of them serves as context for many of these studies, and as a way of entering the psychologies they inhabit. Thus, the familiar is but a doorway to enjoyment, particularly of the skillful use of materials found here.

Upon first entering the Schmidt, visitors will encounter Renella Rose Champagne, a hard-knocked but hopeful singer whose life is portrayed by Louisiana-based performance artist Stephanie Patton. The clichéd details of a life are pinned to the gallery wall like dead and dusty butterflies: turquoise cocktail napkins stamped with Renella’s wedding date, cheap nylon nighties, a CD listening station (You had your eye on everyone at the party/All the girls resembled Pamela Anderson Leeee...), and some photos of Renella as a spokesmodel for weirdo comfort products, such as an anxiety harness and a heart pillow (“a soft cushion that gently supports the weary heart”).

The impression is twofold: First, Patton, who has played Renella for 18 years, confidently speaks to how humor and the careful indexing of personal objects can be used to explore the self. Second, the installation preps viewers for the works to follow, many of which also use levity and the commonplace to investigate how we present ourselves and how we are perceived.

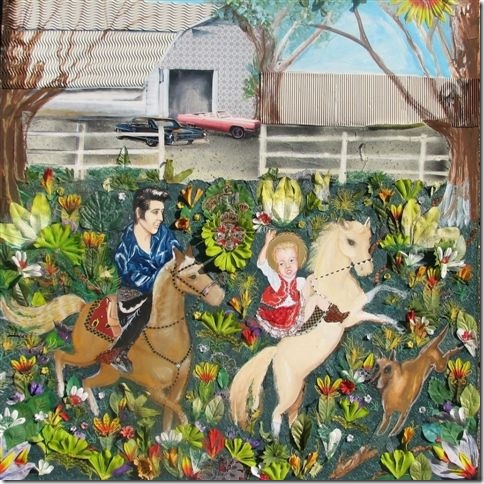

We see this in Kathy Yancey’s mixed-media collages; they enshrine the wishful thinking of the young in settings which blend fables with the common, such as a Hieronymus Bosch-like garden assembled from the plastic petals and leaves one might find at a dollar store. Within this thicket, a little cowgirl rides a white pony alongside Elvis Presley, who appears in pre-bloat form and looks upon her with fatherly love.

A thumbnail of this same image appears as a painting in Yancey’s Vision in the Waiting Room, which also portrays how invention can allow us to escape our immediate surroundings and transport the self from drudgery, or even misfortune, to faraway places filled with color and light — in this case, an ocean buoyantly cluttered with bright fish and coral. Yancey’s nod to Bosch, as well as Matisse’s dancers, gives another layer of context to her assemblages, and they are some of the most accomplished offerings found in the show.

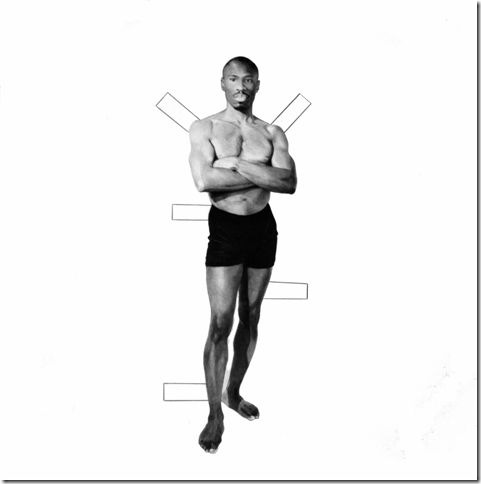

Also notable are Damond Howard’s transformative wall-sized charcoals of African-American men. Their side-by-side analysis of legitimacy and stereotyping expand figurative drawings into historical and social condemnations.

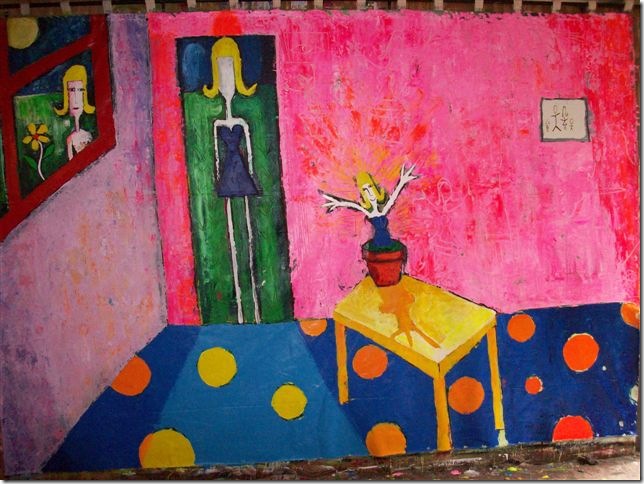

On to the Ritter Galleries, where the exhibit continues in darker confines that are illuminated by Carl Knickerbocker’s raw and garish palettes. In this self-taught artist’s hands, what might typically appear as a cheering living room is instead a fairy tale gone awry, sort of along the same lines as Neil Gaiman’s novel-turned-movie Coraline. As with many of the works in this show, all is not as it initially appears, and one is left to consider not only what’s before the eyes but what has been left out, and why.

In Knickerbocker’s work, this includes the featureless face of an elongated woman, looming in a doorway while a smaller version of herself emerges from a garden pot. It sounds amusing, but the artist’s disjointed perspectives indicate something is wrong.

SouthXeast closes with an installation by Miami-based artist Beatriz Monteavaro: We Saw Creatures groups 62 drawings, four amorphous soft sculptures, four latex heads and a “Serpent to Sting You.” First off, black light rules, and is an element woefully underused in contemporary art because ignoring it discounts the power of time travel. By this I mean black light’s ability to instantly transport us to the tastes of pre-adolescence, such as collecting glow-in-the-dark posters or visiting haunted houses at county fairs.

Monteavaro, however, is unabashed in her tribute to this age, and her monster art features devils, mummies, lizard creatures, and other old-school horror villains. The whole gallery has become the room of a child who’s spent hours reading horror comics or watching Creature Features. Rather than gruesome, the installation is nostalgic and delightfully innocent in its backward glance toward youth, before we learn that there are worse things in the world than the ones we dream up.

southXeast: Contemporary Southeastern Art runs through April 9 at the Schmidt Center Gallery and through March 5 at the Ritter Art Gallery, Florida Atlantic University, 777 Glades Road, Boca Raton. Hours: 1-4 p.m. Tuesday through Friday and 1-5 p.m. Saturday. Admission is free; donations welcome. Call 561-297-2966 or visit www.fau.edu/galleries.