After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, U.S. authorities rounded up thousands of Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast and shipped them to internment camps, fearing they might be traitors.

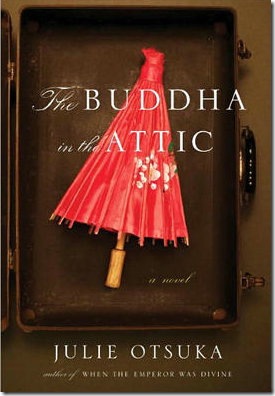

In her compelling new novella, The Buddha in the Attic, Julie Otsuka captures in spare prose the paranoia of that period. She opens by describing the arduous voyage by ship of mail-order brides from Japan to California early in the last century. The story continues with their crushing disappointments and hardships, and ends with the mass deportation of individuals and families to camps far from the coast.

There is no plot line and no central characters. Otsuka effectively uses the collective “we” to describe the brides and their travails.

“On the boat we were mostly virgins,” the book begins. “We had long black hair and flat wide feet and we were not very tall. Some of us had eaten nothing but rice gruel as young girls and had slightly bowed legs, and some of us were only 14 years old and were still young girls ourselves.”

The Buddha in the Attic follows Otsuka’s 2002 debut novel, When the Emperor Was Divine, which was greeted with wide critical acclaim.

The mail-order brides crossed the ocean with a mixture of joyful anticipation and dread. They carried pictures of their future Japanese-born husbands, along with silk kimonos for their wedding night. But the men they met on the dock bore little resemblance to the pictures taken 20 years ago. For many their wedding night was a nightmare of forced sex.

Some settled on farms, others became maids, and all faced the threat of unwanted sexual advances, sometimes from bosses. Some were barren and others bore numerous babies. As the children grew, they quickly learned English, absorbed the culture and rejected their parents’ ways.

“They forgot how to pray. … They gave themselves new names we had not chosen for them and could barely pronounce. … Mostly, they were ashamed of us. … Our heavy accents. … Our deeply lined faces black from years of picking peaches and staking grape plants in the sun.”

Otsuka based the story on extensive research, and it shows. She never tries to simplify the brides’ experiences or fit them into a mold. Some marriages endured and others fell apart. Some brides left their husbands and returned to Japan.

Because of the author’s reliance on a collective voice, none of the characters are fully formed. A few women are named, but they quickly disappear without leaving a lasting impression. And yet the collective hardships and anxieties will linger in the imagination, leaving no doubt that Otsuka is a writer with a beguiling fresh voice.

Otsuka writes about the brides without moralizing or judging. She is particularly effective in invoking the fear and isolation that gripped Japanese-Americans in the wake of Pearl Harbor.

“There was talk of a list,” she writes. “Some people being taken away in the middle of the night. A banker who went to work and never came home. … A few more of our men disappeared every day. … Soon we were hearing stories of entire communities being taken away.”

Families packed suitcases with their necessities. One woman left “a tiny laughing brass Buddha up high, in a corner of the attic, where he is still laughing to this day,” hence the book’s title. Soon looters began breaking into the now-empty houses.

The final chapter, “A Disappearance,” describes the mostly indifferent reaction of neighbors to the departure of the Japanese-Americans. Rumors circulated about caches of weapons found in their cellars. People wanted to believe that their former neighbors were “good, trustworthy citizens,” but “of their absolute loyalty we could not be sure.”

Otsuka ends this haunting novella on this poignant note, “We speak of them rarely now, if at all. … All we know is that the Japanese are out there somewhere, in one place or another, and we shall probably not meet them again in this world.”

The Buddha in the Attic, by Julie Otsuka; Knopf; 129 pp.; $22

Bill Williams is a freelance writer in West Hartford, Conn., and a former editorial writer for The Hartford Courant. He is a member of the National Book Critics Circle and can be reached at billwaw@comcast.net.