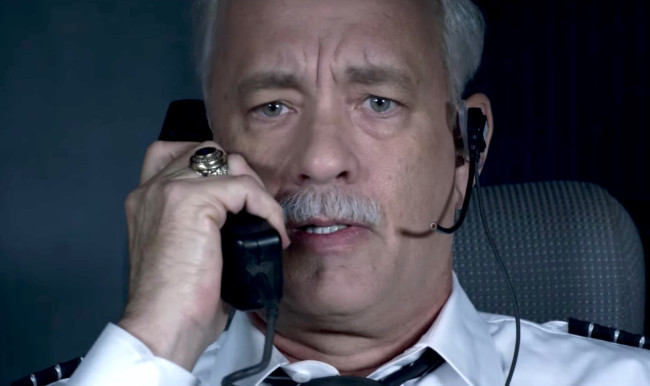

Arriving midway through Eastwood’s drifting narrative, it’s presented without a musical score, respecting the soundless vacuum of the cockpit where the split-second calculations took place. Communications between Sully (Tom Hanks), his copilot Jeffery Skiles (Aaron Eckhart) and an air-traffic controller exude calm and authority despite the increasingly likely prospect of mass death. Even the passengers “prepare for impact” without the pandemonium usually associated with aviation disaster pictures.

There’s a sly subversiveness about Eastwood’s reticence to fall into conventional scare-rhythms. For a movie shot for IMAX, these few real-time minutes of Sully are the closest it comes to giant-screen spectacle, and even they are subdued. Instead, Eastwood deploys the super-hi-def cameras and giant screens on a dialogue-rich screenplay set in monochrome interiors — hotel conference rooms, government chambers, television studios — where it pursues a more philosophical conflict.

Todd Komarnicki based on his screenplay on Sullenberger’s autobiography Highest Duty. It opens in the immediate aftermath of the water landing, which is where it stays for most of the picture. While the press is canonizing him as an American hero, the National Transportation Safety Board’s assessment is not so sanguine. The well-dressed bureaucrats, played with varying degrees of accusatory impudence by Anna Gunn, Mike O’Malley and Jamey Sheridan, defy the captain to justify his actions and put 155 lives in danger when their models project a safe landing back at LaGuardia or Teterboro.

The most nuanced performances from these familiar character actors don’t make us see them as anything other than bean-counting, pinheaded functionaries deigning to question the Great Man. Sully’s resistance to their investigation strikes one as a quintessentially Eastwoodian dichotomy: Intuition versus algorithms, individual humanity versus state soullessness, Man versus the Machine. It’s a Frank Capra story for modern times.

Of course, with the hindsight we bring to the movie, it’s all too easy to slide in line with the man who selflessly landed a plane on a river without a single casualty. If there’s any fault in this touching and immensely likable movie, it’s that Sully worships Sully like a deity. He’s the picture of nobility, humility and healthy self-doubt. He doesn’t curse, he doesn’t lose his temper, he’s a generous tipper and his ego seems the circumference of a pine nut. His only intimation of dishonesty is that he may have, perhaps, through his website, created the impression that his then-upstart flight-safety consulting firm was larger than it actually was. When he replies to Skiles that “I’m not usually accused of being a bullshitter,” it’s easy to believe him.

And yet, intentionally or not, Eastwood’s movie pivots from a study in defiant individualism to a celebration of the collective spirit when it mattered most: New York City’s response to the water landing. Families are separated and then reunited, and panicked passengers are rescued from freezing temperatures as help arrives by ferry and helicopter alike. A city’s entire transportation infrastructure converges to complete the miracle Sully set in motion.

A pair of pilots, a flight crew and a multi-headed hydra of first responders needed to get everything right to save 155 people, and it’s impossible to watch these scenes without growing proud and misty-eyed. Sully will not rank among Eastwood’s richest features, but this classical crowd-pleaser lands just right.

SULLY. Director: Clint Eastwood; Cast: Tom Hanks, Aaron Eckhart, Laura Linney, Anna Gunn, Holy McCallany, Jamey Sheridan, Mike O’Malley; Distributor: Warner Bros.; Rating: PG-13; Opens: Friday at most area theaters