By Myles Ludwig

Amid gods and grotesque wonders I meandered in an alternate universe. The atmosphere vibrated like a plucked string on a cosmic harp playing the music of the spheres.

Creatures escaped from a child’s nightmare — lurid monsters with no discernible reference, deformed horrors, superbeings with powers defying rational explanation — surrounded me.

Weird tales walked the aisles of a permanent Halloween; a world of the new mythology.

But I was not intimidated.

Here were kids in capes and costumes, lifting insectoidal heads and tipping back androidal helmets to eat hot dogs and Doritos. They inhabited characters of visual fantasy while their parents perused window treatments, laminated flooring and water filtration systems on the floor above.

I wondered what connection they felt with the heroes and heroines and oddments they represented. What were the anticipated benefits of being a muscle-bound green-skinned Ninja turtle, a fully metalized robot from another galaxy? I was amused by a diminutive young girl in a Viking-medieval costume wielding a hammer of Thor taller than she was.

This was the PalmCon at the Palm Beach Convention Center, a garish but well-mannered mash-up bazaar of the bizarre and fan festival centered on the comic book and graphic novel forms and associated collectibles, where reality as we know it has little bearing and the two-dimensional reaches beyond space to some fourth of fifth or sixth dimension. A place where interstellar travel is as commonplace as driving the Toyota to the closest Costco.

Everything was for sale. Memory was side-by-side with the most futuristic; boxes filled with comic books arranged by subject like record albums, old-fashioned vinyl; action figures; custom costumes; independent publishing entrepreneurs; storyline writers images made while-you-wait by young artists with aspirations to be some version of the two Cleveland high school kids like Jerry Siegel and Joel Schuster, who created Superman in the 1930s, or the next Frank Frazetta, the anti-Norman Rockwell.

I was a comic book fan as a kid. Not a fanatic, but certainly I dreamed of what it might be like to leap tall buildings in a single bound, be faster than a speeding bullet; have X-Ray vision … and for only a dime.

Comics certainly stocked the fires of my imagination. They also influenced my sense of visual perspective. They’ve had an indelible impression on the cinema of makers of my generation, and I’m not thinking of movies based on theme park rides or iron people and angry hulks. They also introduced me to the great works of world literature from H.G. Wells and Arthur Conan Doyle to James Fenimore Cooper and Alexander Dumas; from Melville to Homer and Shakespeare.

I had a particular fondness for the 169-volume series of Classics Illustrated, created in 1941 by Russian immigrant Albert Kanter. These digested traditional literary works and presented them in comic book form. I remember my father rewarding acts of my good behavior with gifts of a new issue, an opportunity for a few hours of parentally approved private escape.

Comic books have a long and distinguished popular culture lineage. They are descended from “pulps,” initiated by Frank Munsey’s repurposed Argosy in 1882. Printed on inexpensive pulp paper with glossy lightweight covers, they encompassed detective stories, Westerns, horror and science fiction. These were descendants of the weekly fiction magazines, dime novels and penny dreadfuls and dominated the men’s magazine market for some 60 years, before giving way to comic books and the “sweats,” or he-man magazines, that flourished between the two world wars and were churned out by “fiction factories,” as they were termed by Harry Steeger, the liveliest of pulp publishers, who ran Popular Publications.

Walter Gibson, best-known for his work on The Shadow, said, “I had to hit 5,000 words or more per day,” and it was said he “typed so furiously that his fingers bled.” Westerns flowed from the typewriter of the prolific Frederick Schiller Faust, who produced some 30 million published words. Though he was most closely associated with the Western genre, “he professed to find the actual West ‘disgusting.’ In fact, he wrote most of his stories, living amid “the Renaissance splendors of his villa near Florence, Italy.”

But, according to pulp writer Henry Kuttner, “there is but one adventure story … it is laid in the South Seas … a mysterious map, a cannibal island, a sunken treasure, a beautiful girl, a crew of Lascars … and an octopus or two.”

Pulps were displayed on the newsstands of the day, their covers considered key to sales success. “We didn’t have Playboy yet to appeal to the prurient interests of young boys burgeoning into manhood,” said one of the artists of the time. They were painted in the mode of “cultural anarchy” and clearly influenced a generation of modern Pop Art painters like Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol and even Jeff Koons.

It was “the art that dared to be wild,” wrote James Van Hise.

The sex-drenched pulps of the 1930s — Spicy Detective, Spicy Mystery and Spicy Adventure — were largely “the brainchildren of printer-turned publisher Harry Donenfeld and Frank Armer and their Culture Publications.” They “were … raunchier than the previous sex pulps” and their illustrated covers defied censorship with two words: “no nipples.”

But the U.S. Post Office clamped down and their retail distribution was hampered. Ultimately, Donenfeld and Armer abandoned the category for comic books, providing a home for the Superman and Batman characters

The decline of the pulps began in the 1940s, and they were succeeded by comic books which sold millions — Action Comics and Superman sold over 2 million copies per month. By the end of the war, “the circulation of comic books was four times that of the pulps.”

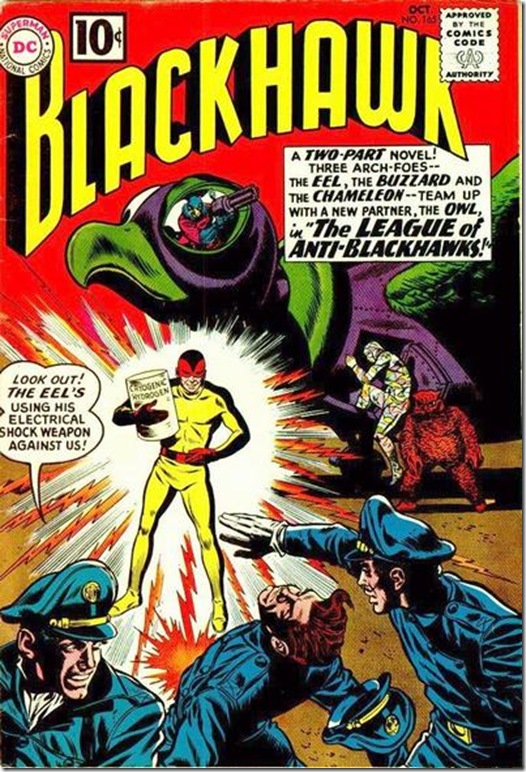

So I bought a couple of pieces of my own past: Classics Illustrated No. 133, The Time Machine, by H.G. Wells, with a cover illustration of a guy riding some kind of vehicle that would be at home on the cover of Popular Mechanics, and Part 1 of the two-part “novel” of the Blackhawks vs. a gang of their arch-foes, the League of Anti-Blackhawks, consisting of the Owl, the Eel, the Chameleon and the Buzzard.

Myles Ludwig is a media savant living in Lake Worth.