By Myles Ludwig

I’m not surprised that Franz Kafka woke up one morning and imagined he was some kind of giant beetle.

He needed someone to talk to.

A writer’s life is a lonely life, particularly a writer who makes fiction or poetry. There you are with a world in your head, struggling with near impossibility of describing it perfectly, not only to yourself, but to someone else, too. You need some kind of Google Glass to see what’s going on in there and somebody else to tell you whether you got it right or not, whether or not you allowed the beast within to speak in a tongue others could understand.

It never really comes out the way you want it to, but some nutso force in there keeps trying to get it right — whatever “right” is. As Kafka said, “Man cannot live without a permanent trust in something indestructible within himself, though both that indestructible something and his own trust in it may remain permanently concealed from him.”

Journalists have it easy in comparison. The world is at their feet and once they find the door to get in, the conventional language is available.

I’ve noticed that movies about journalists sometimes work. I’m thinking of All The President’s Men (P.S.: It’s Watergate Remembrance Week) or The China Syndrome (which then happened in Japan). Even TV’s talky Newsroom. But, those are about the writer’s life, not the writing. And they usually glamorize the job. Movies about writing itself and the people who make fiction or poetry almost never come off. Understandable. Who wants to sit through some 90 minutes of watching someone chewing the end of his pencil, staring into space and keying in sentences, half of which are likely to find themselves in the delete file?

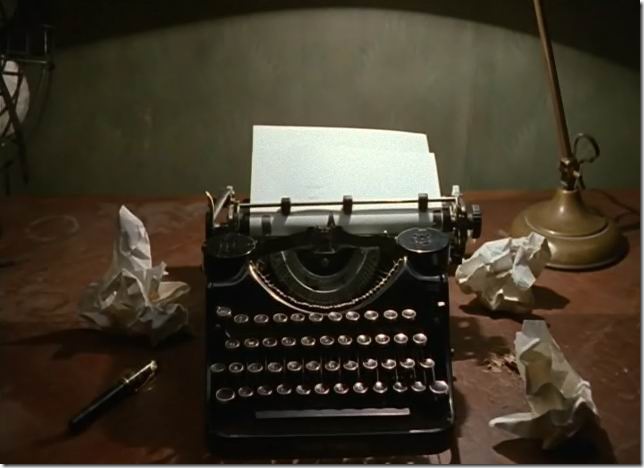

At least in the old days, the clackety-clack typewriter days, you could see the writer crumbling up a piece of paper in frustration and hook-shotting into a waste paper basked. Now, people don’t have typewriters or wastepaper baskets. Some stories about writer’s lives can work if they are a) tragic enough or b) adventurous enough. Otherwise, it’s a lot of complaining.

Every time it comes up in conversation, in a classroom or in some media interview, the big question is: where do you get your ideas from? It’s the same question asked of poets, painters, songwriters and guitar players and everyone has the same answer: Who knows?

I like what Bono said to Charlie Rose a few nights ago. He described putting on his headlamp and climbing down into the mine to see if there’s anything worthwhile digging. A few canaries have died along the way, he noted.

It’s no accident Kafka made the bugman a traveling salesman like his own father. I can’t say for sure where the idea for this came from, except that all the noise about The Great Gatsby made me think about one of my most influential authors, F. Scott Fitzgerald. Particularly his Pat Hobby stories about a desperate screenwriter. But even Gregory Peck couldn’t save the movie about his descent into Hollywood’s seven circles of hell.

The other question is: Why do you do it?

You try to rise to the bait and pretend you can explain, but really, you can’t.

Believe me, if you could provide some kind of reasonable answer, the question wouldn’t be asked of everyone who sits alone in a room trying to get that color, that melody, that lyric, that verse, that story out of your head. How does a physicist explain the inner being of a quark or why the string theory makes sense even if you can never see it twanging in all that dark energy?

I remember that Eric Dolphy, the great jazz sax player, used to say music is everywhere; you just have to pluck it out of the air. It’s the right pluck that’s tough.

One of the things I like best about writing these Sunday specials is that I can wait all week for that pluck, for something to say. Do I want to comment on current events – Obama’s gray hair, the IRS, Angelina Jolie’s breasts — and then, boom, as they say in Hollywood, here it is. Write about writing.

The worst thing about writing is that you’re only halfway into the room. Mostly, you’re making mental notes or thumbing yourself a text about how this or that might fit the thing you’re crafting.

As Kafka said, “I have hardly anything in common with myself and should stand very quietly in a corner, content that I can breathe.”

Myles Ludwig is a media savant living in Lake Worth.