One hundred years ago this month, Europe was in the throes of a buildup to catastrophe in the aftermath of the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on June 28. It would climax, as we all know, in a four-year conflict that for its savagery and scale of destruction was unequalled in all of human history.

World War I set in motion the even more cataclysmic Second World War, which followed only 20 years later, but which is mostly inconceivable without the loosening of societal cement that the Great War brought to bear. “The long era of the peaceful, easy intercourse between nations, of gracious living, of good taste, of good manners, of prosperity, was gone forever. The world lost its confidence in the future,” the pianist Arthur Rubinstein wrote in My Young Years (1973), the first volume of his memoirs.

Because the war is forever entwined with the twilight of monarchical dynasties that had held the European stage for hundreds of years, and because we still feel a tug of attachment to all that royal pomp, there is a faint patina of romance over the early days of the war that makes the succeeding butcheries of the Somme, Verdun and Passchendaele even more striking. Barbara Tuchman memorably pointed to the funeral in 1910 of England’s King Edward VII as the last gasp of that world, and to see the film of that event (as you can on YouTube in a terrific 1964 BBC documentary called The Great War), brings it home in a truly vivid way.

I have been trying to puzzle out the reasons for the war for some time now, because all my reading and study of it (and a brief interview I did 20 years ago with a 99-year-old veteran of the conflict) only led me to deeper confusion about the actual causes of the event. If World War II was a true fight of good against evil, World War I seemed more to me like a willing mass suicide.

But I think now that the key to the whole thing, aside from sclerotic governments and aggressive hypernationalism, is that the war was conducted in the wake of a massive increase in technological power whose impacts were barely known, and that could only be understood through a painful, exsanguinous working out in the fields of Belgium and France. Germany and France went to war with the mindset of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 — which was distinguished by some improvements in rifles and cannon — but found themselves in a very different situation with the addition of telephones, automobiles, tanks and airplanes.

Technological improvements kept arriving throughout the fighting, but it took some time for soldiers and commanders to figure out the enormous increase in destructive power that was now available to them (and being humans, we had to push it to its limits and see what would happen). The late British military historian John Keegan, in his 1999 account of the war (The First World War), notes that while much of the communications technology, including embryonic radio (the first U.S. broadcast was in 1920), could have been used to douse the conflict, its leaders were not ready 100 years ago to do so:

“Honorable and able men though they were, the servants of the chancelleries and foreign officers of the great powers in the July crisis were bound to the wheel of the written note, the encipherment routine, the telegraph schedule. The potentialities of the telephone, which might have cut across the barriers to communication, seem to have eluded their imaginative powers. The potentialities of radio, available but unused, evaded them altogether.”

The situation changed in the following four years, but again, it was through a very bloody trial and error, with Great Britain, France and Germany losing 2 to 3 percent of their entire populations by the time of the Armistice in November 1918. Many of those losses came on days of tremendous butchery, as the opposing armies tried over and over to overwhelm the other side with decisive force. And my reading tells me that a lot of that came about not just through a rebooting of effective campaign strategies of the past, but because the participants were absorbing new technological realities and then trying them out in the field, such as massed tank attacks, poison gas, and aerial bombardments.

I think we have had much the same problem in the past century, and are seeing it particularly acutely in computer technology today. We don’t take the time to think about the possible effects of the new technologies we have; we just use them and society adapts as well as it can. But some of these things have been truly wrenching. Many of the old industries, married to older technologies, are in chaos as instantaneous communication remakes the business and cultural maps. There are societal effects, too: Does the easy access the Internet affords to a person’s rawest impulses explain why so many people who should know better — police, clergy, educators — find themselves facing charges of sex offenses?

Surely this extends to the firearms plague as well; it’s too easy for people to permanently end an argument, as the angry ex-husband in the Houston suburb did last week, killing six members of his ex-wife’s family. Perhaps it’s time for our society to have some sort of permanent institution — a technology war college, if you will — that examines the new technologies and works out as many of the possible ramifications as it can. It would not necessarily slow any arrival of something on the market, but perhaps it would be helpful if things such as cellphones had come with warnings or even disabling features to address the sending of text messages while driving.

We may very well be at that point in our civilization, a place where so many new technologies are being introduced so quickly that we all need a moment to think about these things together before we waste too many people’s lives finding out how enormously potent our technologies really are. Soon drones will be delivering packages, and robots will be handling routine domestic duties. Shouldn’t we think about the bad and good things that can happen when they do, and before they do?

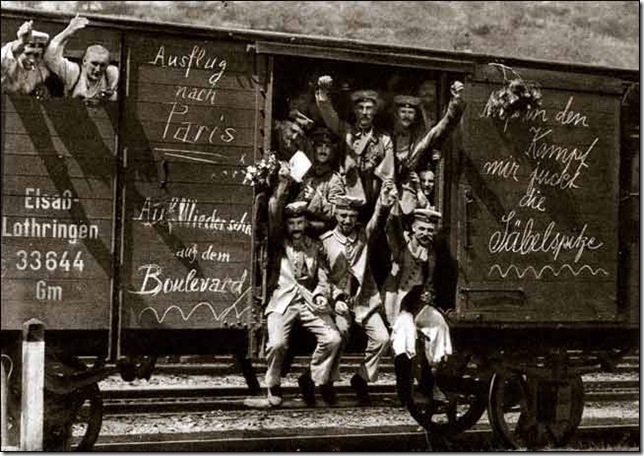

The 10 million people who died in World War I might have benefited from some sober thought somewhere in the corridors of power about the potentialities that 40 years of peace had birthed. Perhaps one of them would have seen a stalemate in the offing and recommended an exit strategy before all those young men boarded the trains and marched through the fields. It’s not likely that anyone would have listened, but it might have added a muscle reflex to political thought that could have gotten stronger with time and even bigger stakes.

At a relatively early point, the managers of World War I lost control of it. It was technology that took it out of their hands, and the lack of still-better technology that kept it that way. Like the monarchs and the generals of July 1914, we do not have a good grasp of what our machines are capable of unleashing, and in honor of the memory of the millions of brave people who died so pointlessly a century ago, perhaps we should muster the best of our humanity and try to forecast their darkest possibilities.