By Myles Ludwig

We learn a lot early in our lives, even when we don’t know we’re learning. Those early impressions of childhood set the standards that accompany us for the rest of our lives, for better or worse.

We don’t understand them then, and if you’re at all sensitive to the sashaying vagaries of your moods, you can choose to remain a prisoner in the cellular structure of yourself, or embark on a lifetime path of psychic examination, turning over every rock, looking around every corner of self, peering into every crevasse of personality and lurking on the ledge of consciousness just to catch a glimpse of what’s hidden there, what insists on directing current behavior.

I think the latter journey is balm for the soul, no matter how uncomfortable the trip, how bumpy the road might be at times. As Socrates was reported to have said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.”

But, you don’t have to subscribe to any particular philosophy, psychology or religion to get a sense of which way the breeze blows through the mind.

In our teenage years we are short-fused, walking time bombs of inarticulate imaginings, warring impulses, mysterious urges and misunderstood torments. We are on edge, to put it mildly, quite likely to go nuclear at the slightest provocation. North Korea has nothing on the volatility and enormous capacity for dangerous mischief of a teenager. If parents can survive those years ― and I am a parent ― and come out the other side of that dimly-lit, poorly marked twisting tunnel of struggle with but minor flesh wounds, narrow misses and a relatively intact relationship, they ― we ― deserve a medal for both good conduct and valor.

Adolescence is a state of being in which feelings barely stay afloat on a roiling sea in a perfect storm of hormonal waves and libidinal gales, neither surfable nor sailable. Stuff inside doesn’t just get stirred up, it goes berserk.

This is a lengthy explanation of teenage lust and how I yearned for a chance to take first Princess Summerfall Winterspring and then Annette Funicello to the senior prom.

I was too young for the likes of Ava, Lana, Rhonda, Rita, Veronica and even Elizabeth and even though, much later, I got mushy over Mary Murphy, Natalie Wood ― a frightful mess of a girl ― Eva Marie Saint, and Yvette Mimieux. I really had no idea how difficult the lives of these women were. They were so powerfully beautiful. It took a long time to understand that no one ever tells the truth to a beautiful woman for fear of being cast out of her radiance.

Does even The Shadow know what mystery lies in the hearts of men and women that attract them to each other, anthropology and psychology to the contrary?

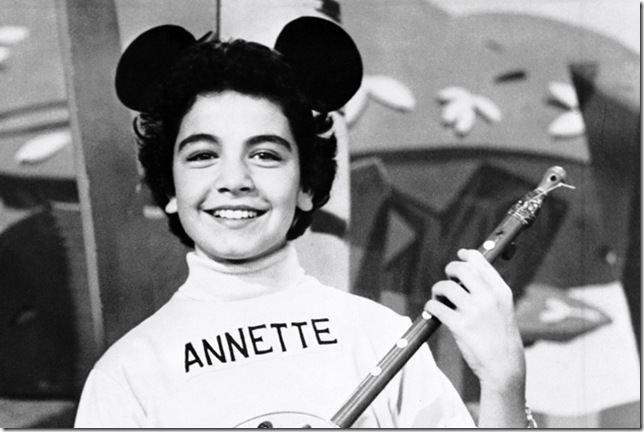

My first crushes were on the quasi-Native American princess who was pals with the coolest wooden dude on TV, Howdy Doody, and then, the teen queen with the outrageously big ears, Annette Funicello. They captured my heart and frankly, set the bar for my notion of sensuality, a notion I’ve lived with ever since. It seems just a teensy bit perverse to talk about them now, but no worse than a middle-age Katie Couric comparing guns with Fitty Cent and kvelling over his business creds.

The Princess of Doodyville, with her dark eyes, perfect lips and long braids, beads and buckskin seemed like purity incarnate ― with a reckless side. She came through the screen in a way that, as the princeling of paradox John Waters said, was both “goody-goody and sexy,” a royally irresistible combination. Oh yes, she was the stuff of boyhood dreams. Oh boy, to be in the Peanut Gallery when the Princess was in that perfect world.

It was many many years later before I learned from my colleague, Professor Jim von Schilling, who wrote the book The Magic Window, that she was considerably more babe than maid. Judy Tyler (nee Hess), who inhabited the virginal ideal of the 1950s, had been a leggy Copacabana chorus girl at 15 and a sultry nightclub singer in Manhattan before donning the costume that shivered the timbers of every pubescent boy in America. In Bob Greene’s 1987 Chicago Tribune review of Stephen Davis’ book, Hey Kids, What Time Is It? (his father Howard Davis was a writer on the show), he said, “according to Davis, she was foul-mouthed and wildly promiscuous … while out on the road for supermarket openings, she would strip on nightclub tables.”

I’m still convinced that if I had met her, I could’ve straightened her out.

After leaving Howdy and his gang of splinters and live cartoon characters, she co-starred as Elvis’s love-interest in Jailhouse Rock and considering what we know about his sexual peccadilloes and amorous adventures, the Princess might well have ruled Graceland had she not met her death, cut in half, in an automobile accident in Wyoming, traveling cross-country with her second husband. It was said that at her funeral, everyone in Doodyville was there. Can you imagine?

Metaphorically, Annette was her direct descendant.

I’m talking about the Annette of the Mouseketeers, not the frighteningly chaste beach bunny of Frankie Avalon’s hungry eye. How could she go for a slicked-back poseur like that? And who knew she would eventually reappear in the guise of Snooki, the pudgy siren of the Jersey Shore?

Annette and I were about the same age. She was one of the original pack of Walt Disney’s wild mice (Oh, those ears!) when the show made its TV debut 1955, though the roots of the Mickey Mouse Club go back to the 1930s. Of course there was Darlene, cute as a shiny button, but for me, Annette had something special. She was exotic and twinkled seduction in her short pleated skirt and sweater.

Compared to this, I remember when I came back to the U.S. after several years in Southeast Asia where the kind of flying white-bearded kung fu masters and moon-walking Bollywood bimbos that so entranced Quentin Tarrantino were typical TV and movie fare, how truly surprised I was by the sexualization of the girls in music videos.

Oh, how naïve we were.