An artist considers found images as important as the images she creates, and now we do not know when and where to give her credit.

From now through May 6, the Norton Museum of Art is presenting a rare exhibit with such characteristics. Tacita Dean, which opened last week, focuses on the photographic work of this British artist, now living in Berlin, who is perhaps best known as a filmmaker.

Consisting of about 30 works, old and new, the Norton is labeling it “the first major museum exhibition” to focus on this aspect of Dean’s work, including some never exhibited before. Charlie Stainback, who served as curator and is also the museum’s assistant director, is a fan of the artist’s quiet “sensibility.”

I am not sure that was good enough. Fans of Dean who may have expected to find her giant film installations, full of color and nostalgia, will be disappointed. The key word to remember is: “photographic.” It is a photo-based show.

Most works presented here as photographs are found by the artist, at flea markets and on her travels, and then altered in some way to make them her own. But how much of a transformation takes place is not clear, and neither is the line after which the “found” becomes “Tacita Dean” enough to put the artist’s name on them.

For instance, more than 140 found postcards appearing side by side and depicting the same view of Washington Cathedral is titled Washington Cathedral (2002). In some, the colors are brighter than others. Some look less yellowish or have bolder lines. We can assume the artist has retouched them or colored them somewhat.

But the source (the found objects) still plays the major role and ultimately we have to acknowledge we are not necessarily looking at a new creation. I could be missing something, but credit should go to the manipulation of someone else’s creation only when the result of that manipulation distances itself from that origin in a genuinely original way. In other words, it should earn its individuality, its independence from that original source, not just add to it.

Then there;s this: “End Shot (what a mess)”; “panic”; “Imagine the scent”; “Dead, no breathing”; and “zoom in.”

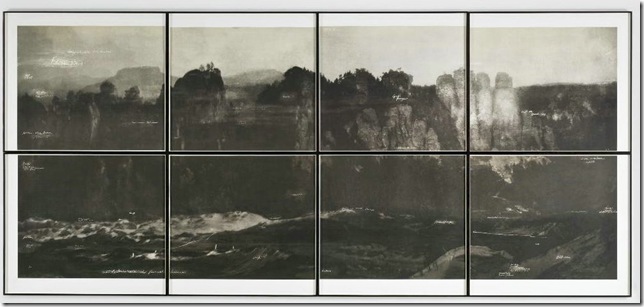

These are tiny handwritten notations in white that appear all over the 20 shots that constitute the 2001 series: The Russian Ending. Each image is a potential film in process and presents us with some form of tragic accident or disaster: a shipwreck, the death of a priest, a bridge collapsing. Superimposed on them are what seem to be director’s instructions for sound, lighting and camera movements.

It makes more sense when you learn that Dean based this series on the notion, apparently a must in the Danish film industry, that a film needed two endings: a happy one for the American audience and a sad one for the Russian.

One photo, Ballon des Aérostiers de Campagne, shows a large hot air balloon apparently trapped in the trees and two baskets dangling from it. The Aérostiers de Campagne was a military regiment in World War I.

The image is almost completely white and not very sharp, but the baskets seem to be carrying passengers and the worst part is, the balloon, in the top right corner, is about to blow up. It is a scene of tension with “panic” and “western front” written on it.

With her handwritten notes, Dean gets us participating in the creative process and imagining the angles, dialogue or characters we would like to see in the making of these films. To her credit, the few curious viewers do get lost trying to make out exactly what those notes say and miss out, perhaps intentionally, on the full picture. More attention goes to the words than the actual visual, and that is a good thing because Dean was not present at the moment these events took place and she did not take the photographs.

Confronted with some of the largest works here, museum-goers stay as long as it takes them to figure out what the image is: a tall tree, stones. Others quickly glanced at the largest images from a distance while reaching for the exit, walking neither too fast nor too slow, so as to be polite.

Among the largest works are Urdolmen (2008) and Urdolmen II (2009). They are meant to be a black-and-white landscape depicting dolmen or ancient burial sites found in Northern Europe. The stones are placed next and on top of one another, only accompanied by a black matte background. The dark shadows lend some drama to the scenes, but they still come across as muted, cold and distant.

Last year’s malfunction of Dean’s Film, at the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, had more energy than this.

Perhaps it is a compliment that most parts of the exhibit feel very somber, but it cannot be a good thing when people entering the Tacita Dean space look as if they happened to be there by chance. Whether it is the lack of energy that fails to capture them or the abundance of it from a room nearby, the crowd clearly is not that interested.

I have a feeling it will keep happening: the crowd looking for the colorful wardrobe display Cocktail Culture or the graphic, in-your-face Jenny Seville show runs into Tacita Dean by mistake, makes a quiet diplomatic exit and forgets about her.

And that, too, would be a big mistake. Dean is highly recognized artist and carries a long list of studies and awards: including the Sixth Benesse Prize at the 51st Venice Biennale (2005) and the Hugo Boss Prize at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (2006). In 1998 she was nominated for a Turner Prize and two years later was awarded a DAAD scholarship for Berlin, Germany. The critics have been consistently good to her.

She does not have to be everyone’s cup of tea, but it is worth noting that what is on display at the Norton is not her most engaging work, but a collection of predictable ones. Let the show serve as a mere introduction to an artist whose most compelling work is absent from here, for now.

TACITA DEAN is on display at the Norton Museum of Art through May 6. Admission to the museum is $12. Hours: 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday, except for Thursday, when the museum is open until 9 p.m; also open from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Sunday. Closed Monday. Call 832-5196 for more information.