Before the publication of this book, few people other than scientists had ever heard of Henrietta Lacks, a poor black woman who died of cancer in 1951.

Lacks was a patient at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore when doctors, without her knowledge or consent, sliced cancerous tissue from her cervix for research purposes. To the astonishment of scientists, the cancer cells began reproducing so rapidly that within a short time billions of them were available for research in laboratories around the world.

“Like guinea pigs and mice, Henrietta’s cells have become the standard laboratory workhorse,” the author writes in her fascinating debut book.

The book garnered rave reviews and jumped onto The New York Times bestseller list shortly after its release. Skloot is a smooth writer, but the book is almost too ambitious in scope. It tries to meld science, race, poverty, family, ethics, medicine, religion and business, but the narrative is sometimes confusing as it jumps back and forth in time, place and theme.

Skloot first learned about the amazing cells — dubbed HeLa for the first two letters of the donor’s first and last names — in a college biology class in 1988. Her curiosity led her eventually to embark on a decade-long search to learn more about Lacks and her five children, who for years had no clue that their mother’s cells were being credited with numerous advances in medicine, including development of the polio vaccine.

Excitement about the immortal cells led to wild speculation. One of Henrietta’s sons thought that serum made from the cells might allow people to live for 800 years.

The author’s detailed discussion of cell biology may cause some readers’ eyes to glaze over. The more interesting parts of the book involve Skloot’s tenacious, almost obsessive, search for information about the Lacks family, as well as her discussion of the ethical issues involved in cell research.

Initially, the Lacks children wanted nothing to do with a white author, but Skloot’s dogged persistence gradually won their trust. As they opened up, she pieced together a family history born in slavery and marked by rural poverty, discrimination, crime, mental illness and superstitious beliefs.

As Lacks’ children and grandchildren learned about the importance of their mother’s cells in medicine, they wondered, in the words of daughter Deborah, “how come her family can’t afford to see no doctor.”

One of the most affecting episodes in the book comes when Henrietta’s children finally are invited to Johns Hopkins to view their mother’s cells and watch them divide and grow under a microscope. As a researcher points to a cell splitting in two and explains that both cells will have their mother’s DNA, Deborah stands mesmerized and whispers, “Lord have mercy,” as she covers her mouth with one hand.

Although Johns Hopkins never profited from the sale of HeLa cells, others did. One commercial laboratory charges from $100 to nearly $10,000 per vial of her cells, which grow “like crabgrass” and have been an unquestioned boom for scientific research. More than 60,000 scientific articles have been published about research using HeLa cells.

Scientists have not explained why Lacks’ cancer cells turned out to be the ones that would fulfill their dream of finding a continuously reproducing cell line that would never die.

Readers naturally might wonder about the legality of using excised tissue for scientific purposes without a patient’s consent. Surprisingly, it was not illegal in 1951 and is not illegal today, as long as the tissue, such as an appendix, was removed with consent.

According to a report issued in 1999, more than 300 million such tissue samples gathered from 178 million people were stored in labs and other facilities in the United States alone. Still, the law is vague about whether and when patients have a right to control their tissues.

Although the book is not perfect, Skloot has written an eye-opening account of a milestone in medical research. It is surprising that it took this long for the full story to be told.

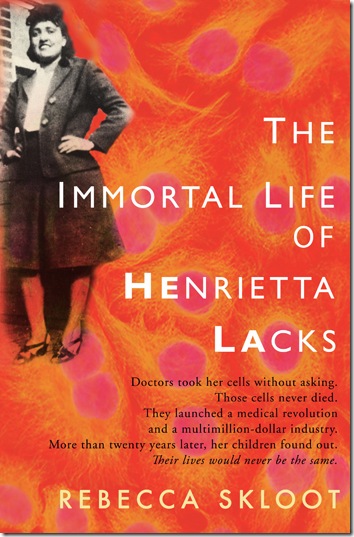

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, by Rebecca Skloot; 369 pp., Crown; $26.

Bill Williams is a freelance writer in West Hartford, Conn., and a former editorial writer for The Hartford Courant. He is a member of the National Book Critics Circle.