No landscape carries the beauty and the beast within it better than the Florida Everglades.

More than 200 images capturing its changing habitants and moods compose an ongoing exhibition titled Imaging Eden: Photographers Discover the Everglades.

I know what you are thinking. Shouldn’t this read Imagining Eden? No. The photography exhibit organized by the Norton Museum has nothing to do with imagination and all to do with vision and sensitivity.

The olive-green walls at the entrance set the stage for the viewer’s own discovery of this world. For an area that wasn’t even considered a serious photographic subject until the 20th century, it sure has caught up. The show includes postcards, maps and plenty of photographs by legendary photographers, including Clyde Butcher and Walker Evans. Some illustrations are immediately recognizable, such as the Audubon prints displayed against a bright yellow wall.

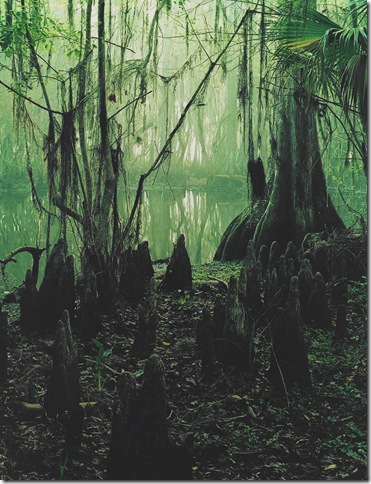

Others, like Eliot Porter’s green-tinted Cypress Slough and Mist, are a pleasant surprise in the otherwise classical-black-and-white room. It was neither the Everglades as a subject nor the use of color that made Porter famous, but rather marrying the two. The scene turns magical, and a bit eerie, as the green hue gets absorbed by a landscape that seems to have been waiting for it.

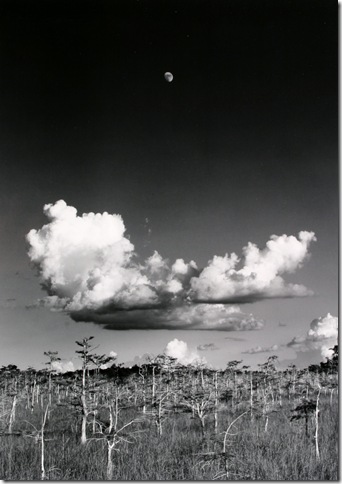

Other subjects, such as clouds and snakes, are less patient and surely threatened to leave the frame if the artist hesitated. Take Butcher’s Moonrise Number Two from 1986. It features a group of clouds suspended abnormally low in the sky. The main one, sporting bright whites, looks like a spaceship that is about to land or take off. Higher up, in the distance, a tiny moon teases us the way it must have teased the lens that captured it.

By the time we reach the next gallery space, everything has changed. The techniques and interpretations get more colorful and daring. A series of ghostly discolored leafs by Jerry Burchfield appears to be at first a botanical experiment, but turns out to be the result of chemicals and light-sensitive paper reacting to the sun. Adding to their scientific feel, the red-tinted lumen prints get titles like Asimina obovata (Pawpaw) and Pinus elliottii (Slash pine).

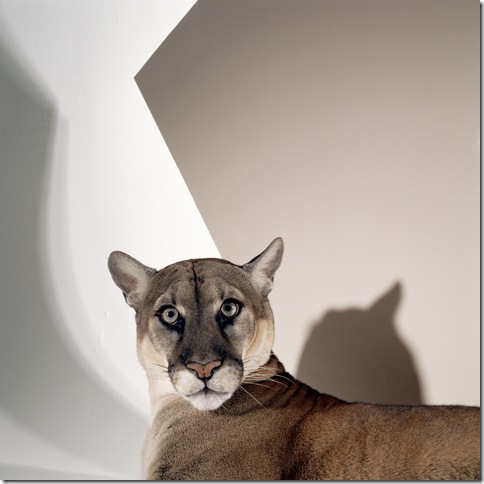

James Balog’s striking Florida Panther, Green Sea Turtle and Brown Pelican are more literal but no less captivating. His large-scale, up-close images of then endangered Everglades species are so detailed and sharp that the animals seem close to abandon the two-dimensional space and join us in the room.

Inspired by its founder, Ralph H. Norton, the museum has paired photographic jewels like these with contemporary works by five commissioned photographers — four of whom had never visited the Everglades.

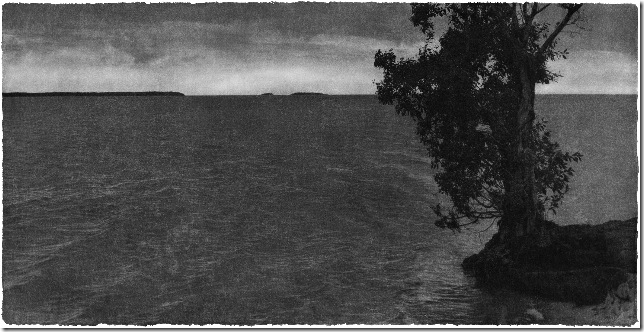

Korean-born Jungjin Lee’s take on this raw environment is poetic and elegant. We are told she is attracted to subjects that possess a certain physical and spiritual power. Her picturesque prints present a tranquil, solitary environment, where silence plays the protagonist. A majestic white cloud stretches out to the left and right ends of the frame in the minimalist Everglades 17.

Its stillness and monumental size are emphasized by the thin layer of water it glides over, like a zeppelin. Meanwhile, Everglades 19 features erect, skinny trees with bare branches reaching out to the center of the image as if pointing at some event or anomaly. The silver trees stand out against a dense, dark background. Nothing is out of the ordinary, except for a twisted, zigzag tree in the middle.

A group of mutilated photographs featuring body parts, masked faces and weapons adorn one side of the wall dividing the gallery in half. They have been drawn on and torn up. They paint a disturbing story that looks half-fiction and half-fact. The installation appears dark, chaotic and violent and it is the product of an artist fascinated by storytelling. For New Jersey-based Gerald Slota, it all starts with a photograph — found or snapped — which later gets cut out, scratched, colored or written on. This collage-like narrative titled The Second and Third Seminole Wars refers to the on-and-off deadly conflicts between the white man and the natives and slaves living in Florida that did not completely end until 1858.

It seems we have stumbled upon an installation still in progress when we reach Jim Goldberg and Jordan Stein’s exhibition space, where landscape images lean against the wall and a boat is suspended from the ceiling. The disorderly presentation is distracting but intentional, as is the collaboration of these two artists presenting as a team. Goldberg is a Magnum photographer with a 40-year career whose daring move to add text on top of his images made him a “bad boy” from early on. Stein is an independent curator currently serving as the curator of centennial projects at the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago. For both, the goal was “to get lost in the experience.”

Adding to the randomness of the layout are surveillance videos featuring wildlife and a giant catalog that is meant to be browsed. Inside it, residents of the Everglades are shown going about their day-to-day life with striking clarity and sincerity. Some images are not very flattering, which is why we find them refreshingly real and beautiful.

In 2007, Dutch photographer Bert Teunissen told The New York Times he hoped to find places that had been “left alone and left in peace.” He got what he was hoping for. Known for the use of light in his domestic European portraits, Teunissen has given us 26 intimate images of families and individuals posing in their domestic spaces, from Okeechobee to Everglades City. In Domestic Landscapes, Everglades, the old and young are portrayed sitting in recliners, sofas or at the dining table and surrounded by family pictures, lamps and books. A Christmas tree makes an appearance in one of the prints.

One photograph depicts a little girl wearing a Halloween kitty costume and another one has a man posing with his unfinished puzzle. His magnifying glass sits on a table nearby. Some spaces are clean and tidy and the people occupying them look comfortable. Other spaces appear drowning in paper or have the elements of someone living in them — even though they are only a part of a house. The expressions vary, too. Some faces look happy, others not so much.

Next to the touching portraits are other series of photographs that serve as a visual diary documenting Teunissen’s time in South Florida.

As we make our way through the exhibition, it is obvious that this landscape, as a muse and as a subject, still has a lot to offer. All it asks of an artist is attention and patience. When it comes to us, the viewers, it only hopes for acceptance.

Imaging Eden runs through July 12 at the Norton Museum in West Palm Beach. Hours: 10 am-5 pm Tuesdays-Saturdays except Thursday, 10 am-9 pm; 11 am-5 pm Sundays; closed Mondays. Call 561-832-5196 or visit www.norton.org.