We wish our world would slow down, unplug, take a breather, but to a group of Italian artists, this world would have been paradise with no sound more soothing than incoming text messages, microwaves and alarms.

Known as Futurists, these artists emerging before and during World War I wished to delete the obsolete past and fast-forward their country into modernity. To do so, they spread the notion of speed and action, like a subliminal message, through poetry, art, music, fashion and whatever other vessel they could find.

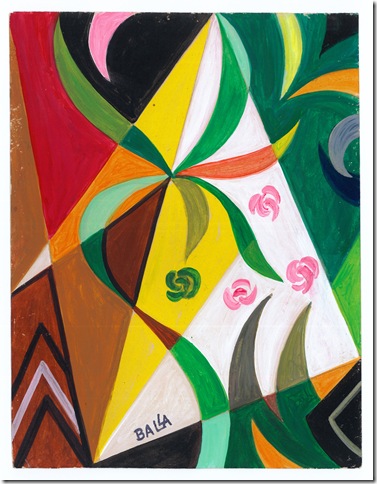

Now showing at the Boca Museum of Art through March 30, Futurism: Concepts and Imaginings explores an art movement that glorified the beauty of the racing motor car over the Mona Lisa. Among the futurists represented through 38 drawings and paintings are Pippo Rizzo, Giulio D’Anna, Giacamo Balla and Gerardo Dottori. Their works are also the subject of a new exhibition opening at the Guggenheim Museum on Feb. 21. The pieces now hanging on the second floor of the Boca Museum may look fragmented, abstract and cubist-like, but the energy in them is indicative of something entirely new.

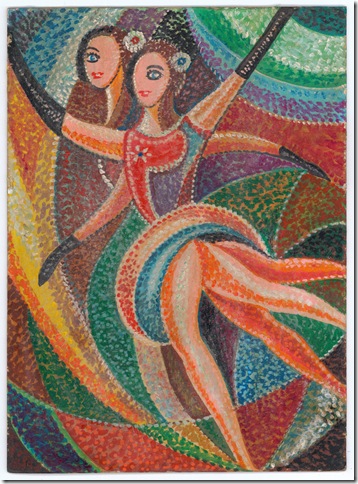

Vivid examples are found on the South wall of the gallery room with Giulio D’Anna’s Au bal (To the Dance) and Ninfe (Nymphs). One features an enthusiastic pair of women heading out to have a good time. Notice the background divided into chromatic planes to suggest motion and time going by. The other piece depicts women of similar features sporting one-piece bathing suits. Three main figures have stopped to face us while the rest swims in different directions. It is as if they were mermaids putting out a show for us to see through a glass tank. There is a sense of urgency and readiness in both images, as if neither scene could last.

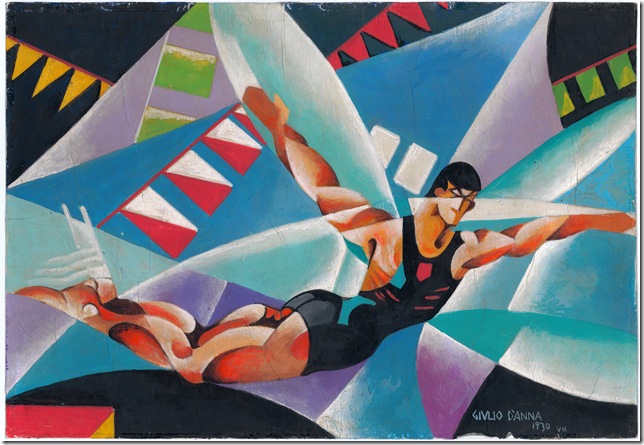

Movement is broken up into faceted planes in Il nuotatore (The Swimmer), also by D’Anna. The image captures a diver suspended in the air seconds before making a splash. Rays of light seem to hit his body at various points, as if gravity was really doing its job and pulling the muscular man down.

New ideas for depicting bodies in motion were always welcomed. Photography contributed a few. For instance, Futurist compositions borrowed the concept of using a series of still images to achieve the illusion of movement. We see the result in Il Uomo (The Man), by D’Anna, where three angles of a man’s head appear all at once as if the head was turning from left to right or vice versa.

Simultaneity was one of the main principles of Futurism. It attempted to compress a range of sensations and experiences over time into one image. By portraying multiple phases of motion simultaneously D’Anna was simply hoping to trick the eyes into believing the head is actually moving. Seeing this old piece outsmart my sharp senses (so I thought) was revealing.

A Futurist’s work purposely lacked fixed points and details. In other words, the entire image ought to be in motion and the eyes should not zoom in on any particular section. This is the case in D’Anna’s Viva L’Italia Aeropastiale (Long Live the Italian Aerospace Industry) where the landscape is kept very basic and sparse.

It is easy to appreciate these creations now, from our present point of view and at a safe distance, but the stance of their creators was aggressive and controversial. None of these works would have been produced had it not been for Italian poet Filippo T. Marinetti’s 1909 “Manifesto on Futurism.” Having read it on the front page of Le Figaro, these radical Italian artists embarked in a new art for a new age. They embraced the energy of modernity and its products: machine guns, automobiles and airplanes.

Many welcomed the idea of war and became soldiers when World War I broke out. All of them went on to promote fluidity and violent change while rejecting traditional morals and cultural institutions such as museums and libraries, which Marinetti had compared to “cemeteries.”

The movement’s militarism and determination, as well as its call for the death of the passive mindset and decorative academic buildings, come across throughout the show. Some pieces reflect this better than others. Nowhere is it more evident than on Pippo Rizzo’s Squadrismo, a tempera piece where armed squads responsible for crushing Socialist union meetings are depicted marching forward. The squadristri uniform shown here consists of a black shirt, a fez and a blackjack (billy club), which was the designated weapon. There is no distinguishable difference among the men marching. Nothing lets one stand out from the rest. The equality and uniformity of their rhythm/pace emphasizes what the picture is: a controlled exercise.

It is nighttime and human figures look up in horror at the violent fire developing before them. The spiraling flames originating from a creepy black hole in the sky are taking down buildings and structures as if they were Lego toys. This is Verso il Centro (Toward the Center) by Gerardo Dottori.

Concepts and Imaginings makes up for its compact size with lively colors and lines and plenty of motion and energy. It is a very enjoyable and agreeable experience, not the type of exhibition that will give you an upset stomach or fall heavy on your mind. It won’t keep you for longer than 40 minutes. It might, however, make you wonder how the future will see us when the visitors and museums of tomorrow decide to explore the art of our time, and whether they will even bother.

Futurism: Concepts and Imaginings runs through March 30 at the Boca Raton Museum of Art. Admission: $8 adults, $6 seniors, $4 students. Hours: 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday, Thursday and Friday; 10 a.m-8 p.m. first Wednesday of the month; 12 p.m.-5 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. Closed Mondays and holidays. Call 561-392-2500, or visit www.bocamuseum.org.