A man tells his friend he lost $27 in Wall Street. The friend replies that he read the stock market news in the paper and asks: “Who got it – Gould or Sage?”

This was brave humor in 1900.

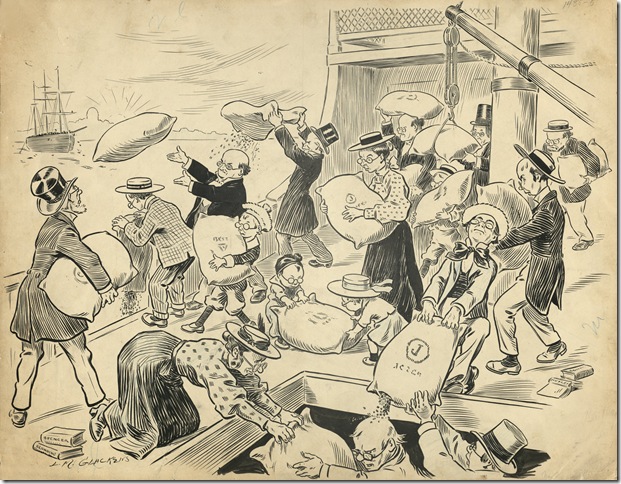

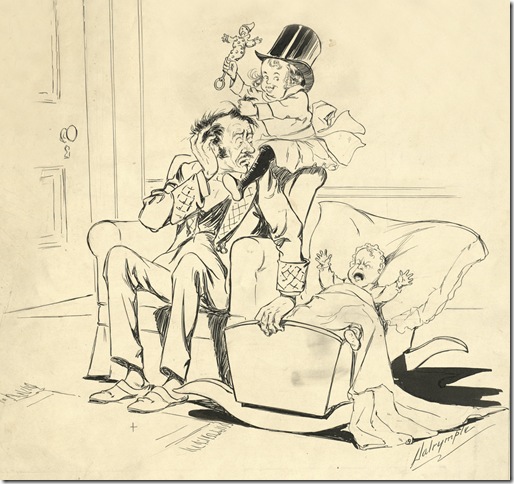

Jay Gould and Russell Sage were well-known railroad executives at the time. The joke derives from a 1900 cartoon by Louis W. Dalrymple that suggests such powerful financiers controlled everything. It is one of 73 equally bold cartoons comprising a ballsy new exhibition at the Flagler Museum.

An automatic mechanism replaces a human judge and is seen turning a wheel that offers standard statements to make while trying a legal case. Some read: “take him down” and “what’s your name?” The judicial process depicted is a random game with the accused watching in horror as his fate is left to luck, not logic. This is “The Automatic Wheel of Justice” (1883), by Austrian cartoonist Friedrich Graetz.

Satirical cartoonists like them taught American humor to take risks and push the limits. Their influence stretches to today’s late-night political television and publications such as The Onion and The New Yorker. Now, they are the subject of With a Wink and a Nod: Cartoonists of the Gilded Age.

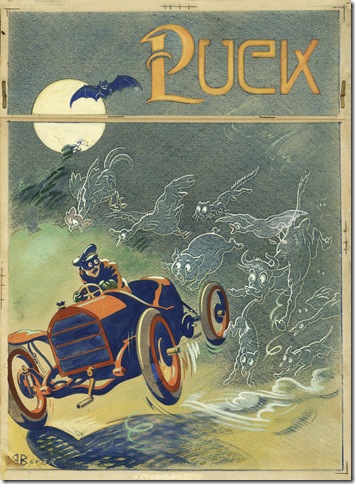

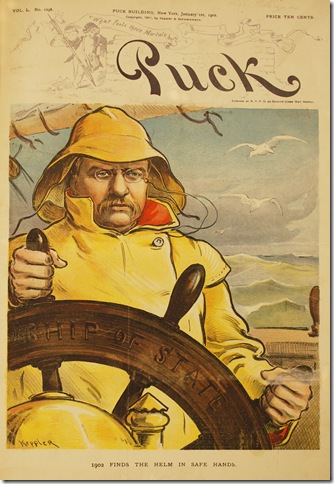

Running through Jan. 3, the exhibition revolves around Puck, a political humor magazine originally conceived in German, with a distinctively sharp voice and a team of progressive artists that went after any target. Its English version, first published in 1877, ran for 40 years and derived special pleasure from focusing on the elite, the spoiled, the corrupt and the unscrupulous. It was the first magazine in America to publish chromolithograph plates on a weekly basis and, might have even been the first to employ, in 1881, what we now call emoticons.

One look at the characters’ outfits and their vocabulary is enough to realize these cartoons are more than a century old. Many seem dated. That they still feel relevant and can make us laugh is a result of the universal themes explored: marriage, immigration, greed, ego, corruption and vanity. Understanding the politics of the time would help us get the jokes, but it is not necessary to appreciate the artistic value of the cartoons, even those in black and white.

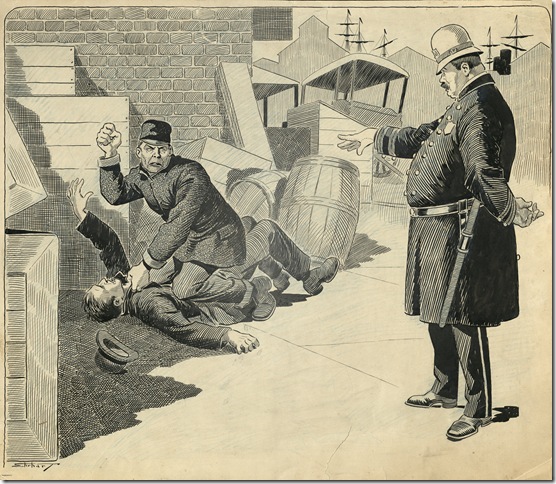

Pedestrians are thrown in all directions and stuck under the wheels of a speeding car owned by a fan of a newly discovered sport: car racing. The owner, here the passenger, tells his driver to keep going despite the casualties. He wants to break the record and, besides, “it only costs $10 a piece to run them down.” “As the Law Stands,” published in 1902 and drawn by John Samuel Pughe, comments on the ridiculous lengths some go to literally win at any cost.

Meanwhile, a crowd of voluptuous women rush to a Turkish bath after getting word of the latest fashion trend: hips are out this winter. Louis M. Glackens’ “Fashion Decree” (1907) makes fun of those willing to do anything to fit in. And in Walter H. Gallaway’s “The Test” (1906), a man wishes to have a mustache like that of German Emperor Wilhelm II. To achieve his goal, he decides to shave while hanging upside down because he read that the beard grows the way it is shaved.

With a Wink and a Nod includes brief bios on the talented cartoonists who gave birth to this incendiary brand of humor during one of the most corrupt times in American history. Their names appear spread out against bright walls that stop us from taking this stuff too seriously. Also included are special issues in striking color and a quick view into the technical aspects of production.

When we reach the second room, the show turns less political and shifts toward modern life and society in general.

Domestic life and spousal interactions are examined in “Wide Awake” (1897). A wise thief tells his partner they better skip the target house because the couple living in it just had a fight, which ended with the husband promising the wife a diamond necklace. Seeing that his partner missed the point, the wise thief goes on to explain that nobody in the house will fall asleep now: The wife won’t sleep thinking about her upcoming new possession and the husband will spend the night figuring out how to pay for it.

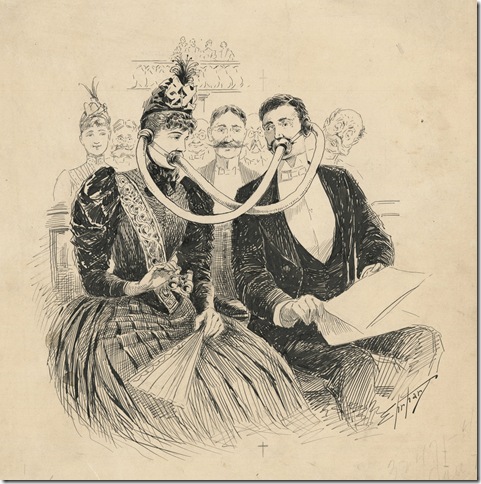

Similar in message is “Interested Solicitude,” by Samuel D. Ehrhart. It shows two men in the distance observing a gentleman protect his wife from the rain with an umbrella. One of the spectators points out the husband’s noble gesture when the other one says: “Yes, he told me yesterday that that dress cost him $75.” Behind the lovely act lies the husband’s true motive: making his investment last.

Another work titled “The Life of a New York Hotel,” by Albert Levering, depicts the three inevitable stages any new trendy establishment undergoes. It is highly relatable. The three-scene drawing starts with the “Era of Magnificence” (during which elegant attire is a must). This is followed by the “Easy-Going Era” (relaxed requirements, less elite crowd) before ending with the “Era of Dilapidation,” when the only customers are stray animals and lonely businessmen.

Puck was founded by Austrian-born cartoonist Joseph Keppler Sr. with the help of Adolph Schwarzmann, a German immigrant living in New York, all of which makes the stereotypical and ethnic jokes housed in the third gallery room the more surprising.

In Frederick Burr Opper’s cartoon “A New Irish Industry,” a line of rundown Irishmen wait for their turn to confess their acts of murders in exchange for a free ticket back to the motherland. The ape-like features assigned to them were intentional, we are told. Cartoonists have always employed exaggeration of physical attributes to convey humor. The Irish just happened to be a favorite target of the time.

The museum does not hang a warning alerting the viewer of the slightly sensitive material about to be seen. Keep in mind, there was no such thing as political correctness to consider at the time. Take each joke and roll with it.

(And be sure to stop by a cartoon titled “Small Loan,” featuring a weeping Donald Trump balancing his checkbook after receiving $1 million from his father. Just kidding.)

With a Wink and a Nod runs through Jan. 3 at the Flagler Museum, Palm Beach. Museum prices: Adults: $18; $10 for youth ages 13-17; $3 for children ages 6-12; and children under 6 admitted free. Hours: 10 am to 5 pm Tuesday through Saturday, noon to 5 pm Sunday. For more information, call 561-655-2833 or visit www.flaglermuseum.us.