In the fall of 1907, the Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke returned to Paris to continue his work with the sculptor Auguste Rodin. While there, he repeatedly visited a memorial exhibit of works by the painter Paul Cézanne, who had died the year before. Those letters informed his only novel, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, as well as his subsequent poetic work, and have become a touchstone of art criticism. While we at ArtsPaper would not presume to duplicate Rilke’s insights, we did wonder what kinds of reactions a critic would get with repeated viewings of the same artworks. We sent Gretel Sarmiento to the Beaverbrook Gallery exhibit at the Four Arts (her review was posted earlier) and asked her to focus on the “star” painting of that show, Salvador Dali’s Santiago El Grande.

Here are Gretel’s letters:

Sunday, February 17, 2013.

I sort of expected Santiago El Grande to be the first work at the entrance of the gallery room. Anticipation does things to the mind.

Yes, the new exhibit at the Four Arts has been out for a while. It has got a long name with the word “masterworks” in it but all everyone keeps talking about is this monumental piece by Salvador Dali. The show features other big names: Turner. Matisse. Freud. Delacroix. Eventually I want to pay my respects to them. Dali, however, is the one labeled “highlight” and the one chosen for the advertising materials, the brochures, the calendar, etc. You get the idea.

And even though I do not like to be told how to feel in advance, I made up my mind to take a look at the oil star.

I guessed wrong. It was not the first image greeting me. I first walked past portraits of French society ladies sporting their funny hairdos, fine jewelry and silky dresses, all the while bracing myself for something of profound significance.

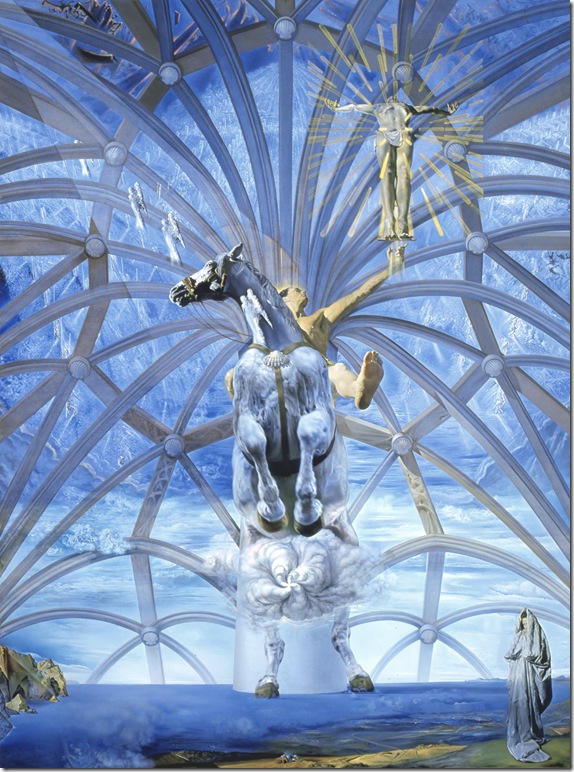

When I finally arrived at my destination I found Dali’s El Grande beautiful. It was stormy and angelical at the same time. It was dramatic, moving. I am sure I am not the first person to say so.

The seashell motif reminds me a bit of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. As you know, she emerges out of a shell with her long, blond locks of hair. That was a much warmer picture. Not like this one. This painting feels cold, icy and instead of coming out of a shell the figures here are trapped under a giant one made of steel or ice. Coincidentally, today is very cold and it does not help that blue is all I’m looking at. The dark blue tone defining the horizon is echoed all the way to heaven.

My initial impression of the piece wore off after a while. I found myself a bit bored, if you can imagine that. It came without warning too, as if my brain had suddenly decided to cut a trial short or skip it altogether and issue a sentence: nothing more to see here. I thought it was my job to fight it, to appeal that decision and change the ruling, so I kept staring.

It bothers me a little that the horse’s head is turned away in the opposite direction from that of his rider, Saint James. As it is, the suggestion is of the man and animal in disagreement. Instead of unity of purpose and thought, I sense there is a separation.

Sneaking out of the horse’s mouth is a piece of its tongue but I could not be sure. Some parts of the painting hang too high and are off limits. If I get too close the men in uniform start getting nervous. One can see icicle-like angels crawling up the animal’s neck. They are like ghosts trapped under its skin. I, for one, am not fond of anything that resembles the supernatural so I find them a bit creepy, but this would not be a Dali without some clever visual twist. Another well-known personal reference is Gala, who appears standing wrapped in a white cloth resembling Christ himself.

Tuesday, February 19, 2013.

There is not much that still interests me about the painting.

It is the animal — painted like a dissipating cloud, an atmospheric sight, a vision of weather, storm, water, pressure — that has my attention. Dali should have known this creature could not be contained with such fragile reins.

This stallion, emerging from the water, is more waterspout than horse. At any moment his front legs will stretch again, reach out for more, advance, and jump over us. The angle of the picture is such that at times it seems as if we were on the ground, staring at the animal’s full belly. Now, you tell me if I should remain at ease standing on such a vulnerable spot.

I do not care much for the procession of angels leading the way, but the tiny figure at the bottom is puzzling. They establish such a big contrast: the massive central figure of the white stallion and the tiny man reclining. They are like David and Goliath. One is a giant and the other one highly insignificant — unless that tiny person is conceiving this whole blue dream. Then, I would say he, rather than Saint James, is the protagonist.

Something I find rather odd is the placement of an explosion being born out of a white flower. I am not Freud, but if it were not for the dust-like effect we would be staring at the animal’s genitals. I remember seeing Dali’s works years ago in the St. Petersburg museum. There were suggestions of male genitalia. I know he liked to shock and trick the eye. It’s hard to imagine him here trying to cover something up.

Thursday, February 21, 2013.

I arrived today in the late afternoon, but I did not go straight to Santiago (I feel like I can call it by its first name now) even though I had only an hour until closing time. Instead I spent some time with other works. Some of them seem far deeper and not as loud, in my humble opinion — God only knows I have only my eyes to trust in this and not a formal education. These other works possess a quiet wisdom, some kind of understanding that one cannot penetrate and that belongs only to the objects and people painted. The more a work resists the more desperate I get to participate, to be involved, included, to be part of whatever it is that is going on.

That is what I like about Charles Lennox, later 4th Duke of Richmond, Duke of Lennox and of Aubigny. It is by an English portrait painter named George Romney. It depicts a young boy with rosy cheeks playing with a red spaniel. The way the boy looks at the dog: calm, serious, benevolent, hints at a level of maturity greater than his age. There is something about his youth that already suggests seniority. I want to know what he is thinking.

Scene of Woods and Water by John Constable is moody, messy and brave. Constable is described here as a romantic English painter who thought of landscape as more than just backdrop. His painting depicts a dark stormy scene. To the right, an old book — presumably the Bible — appears opened as if delivering a message or maybe a punishment. A light illuminates it from above but it does not make the message any clearer. What seems obvious is that it was painted from a place of pain, sorrow and darkness.

I stopped by another piece called West Coast Indian Encampment, which features a group of Native Indians at a fishing camp. They seem relaxed, leaning back, perhaps having a good conversation. They do not look like persecuted people or people who have had relatives killed by strange men. I read that they were known as the Chinookan or Flat Head people. The piece is by Paul Kane, who meant to depict a romantic notion of the “savage” before that less-romantic chapter in history: colonization.

I could not resist and quickly browsed Freud’s Hotel Bedroom and Matisse’s Leda and Turner’s The Fountain of Indolence. All of them add character to the exhibit.

When I finally came upon Santiago I pretended it was by chance. I had wanted to take the painting by surprise, see it without it noticing me looking at it. But the surprise element failed. Just as I felt I knew it better today, the same goes for the painting: It knew me better too; it recognized me.

But it was the first time I really noticed the army of angels and how many of them there are. What a pain it must have been to paint them. I noticed something else: the top part of the crucifix carrying Christ has disappeared. His hands are freed up. No nails are visible. And his palms are facing up as if directing this atmospheric orchestra or evoking someone superior.

Monday, February 25, 2013.

Everybody walking inside the room today let emotions take charge. That is not a bad thing. I am a big fan of emotions myself. But I wonder if it is not simply the painting’s remarkable size driving visitors to say “wonderful,” “amazing” — this within seconds of seeing it. I mean, how much could they really have seen? It is as if their minds were already made up before even looking at the painting. It could be that they know the artist’s name so well they feel a certain obligation toward it. As if by not liking the work they were disrespecting it in some way.

I admit there is a lot to like here. The sight is powerful. But it is too clean for my personal taste. The figure of Gala, for instance, is almost like a cutoff glued unto the rest of the painting.

Also, I did not want to learn too much about the work in advance. That changed today when I finally read the description and immediately felt disappointed.

Nothing is more fragile than an artist’s statement. I try to avoid them myself. If there is any talking at all, it should be left to the colors, the lines. A work will say whatever it has to say and then shut up, whereas an artist’s tendency is to go on and on and on. Maybe I’m wrong, but does he not come to mind as an egotistical prick after reading his quote: “this is the greatest painting since Raphael”?

It must be that Dali’s grandiosity begins where my capacity to appreciate ends.

***

About the work: Originally intended as an altar piece for the Real Monasterio de Escorial in Madrid, Santiago El Grande reflects two of the artist’s interests at the time: the Catholic Church and nuclear physics. It was first shown at the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels. Later on it was bought by Lady Dunn of New Brunswick and given as a gift to the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in 1959. The work depicts the patron saint of Spain, Saint James of Compostela, rising from the sea on a white stallion and holding a crucified Christ as if it were a lantern illuminating the way. Conceived in a dream, it has been described as one of Dali’s greatest paintings.

Masterworks from the Beaverbrook Art Gallery runs through March 30 at the Esther O’Keeffe Gallery at the Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach. Gallery hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Saturday, and from 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. Sunday. Admission is $5; free for members and children 14 and under. Call 655-7226 for more information.