Cinevardaphoto (Cinema Guild)

Standard list price: $29.95

Release date: Aug. 31

For a filmmaker of Agnes Varda’s renown, it’s important to note how few features she has made over her 40-plus-year career. She boasts 47 directorial credits on the Internet Movie Database, yet most cineastes who haven’t spelunked into the deepest depths of the French New Wave know her mainly for four features: Cleo From 5 to 7, Vagabond, The Gleaners and I and The Beaches of Agnes. She’s been a lot more productive than this slim CV entails, but because she’s worked so often in the commercially unviable world of short films – or on equally hard-to-distribute features of an hour in length – her work has been neglected.

Perhaps recognizing this, Varda in 2004 released Cinevardaphoto, a triptych of short films from throughout her career, repackaged as a three-part, feature-length meditation on photography. Newly released on DVD, it’s a fascinating experiment from one of the cinema’s most uncompromising alchemists, dancing effortlessly in the chasms between fiction and reality, narrative and documentary, stillness and motion.

The film starts with her 2004 movie Ydessa, The Bears and Etc., a 42-minute documentary about Ydessa Hendeles, a Canadian artist whose massive “Teddy Bear Project” debuted in Munich in 2003. Over the span of a decade, Hendeles amassed hundreds of black-and-white images of people with teddy bears, culled from family photo albums, then organized thematically or pictorially, individually framed and hung in a gallery space on every wall, floor to ceiling.

Like Varda herself in this series of films, Hendeles constructs narratives out of still pictures, creating elegiac time capsules for a vanished age, and whose oppressive totality is both moving and unsettling. The child of Holocaust survivors, Hendeles doesn’t let spectators of her art forget this, coloring the ostensible innocence of her subject matter with a second room, bare except for a kneeling sculpture of Adolf Hitler. The fact that teddy bears can be so provocative and disturbing is a triumph of artistic reinterpretation, and Varda realizes this and much more in a probing, fascinating look at artistic process, judgment and temperament. Varda’s films are always forthrightly personal, and you get the feeling she recognizes in Hendeles a kindred spirit.

The second film in this triptych, the shorter Ulysses, again captures a nether world between fiction and reality, while adding an ephemerally powerful subtext: Who has a claim on memory? If an image is taken but completely forgotten by its subject, who owns the emotions attached? Again and again Varda returns, with relentless obsession, to a photo she took in the 1950s of a nude boy and a man on a beach near a dying goat. The boy, now an adult with a family, has no recollection of the image, but Varda revitalizes it. More than that, she ruminates, deconstructs and reconstructs the photo from every angle imaginable until it becomes more than the sum of its parts.

The final film in this installment, Salut La Cubans, is a photographic essay, with narration, on the Cuban Revolution. While the other two movies in Cinevardaphoto suggest life from stillness, this time Varda creates life on the screen by animating her shots in a flipbook style. Stills becoming moving images, rhythmically repeated to a musical soundtrack.

Cinevardaphoto is a beguiling survey film that delineates exactly Varda’s place in the film-history canon: born of restless New Wave chutzpah only to transcend its affectations and go her own way. The Cinema Guild DVD release is more than just these three shorts, offering an additional six shorts and a critical video survey, totaling some three hours of combined viewing. Of the six bonus shorts, a couple of them are downright dull, but the most interesting is probably 1975’s Response de Femmes, an 8-minute compendium of feminist arguments spoken by a handful of diverse women against a vacant backdrop. Some of it is dated, but other concerns are as relevant as ever, from the misogynistically desirous mother-whore duality to body-image issues perpetuated by a penis-placating consumer culture.

It doesn’t get much weirder than 1984’s Seven Rooms, Kitchen and Bath, a 28-minute semi-narrative experiment in time, space and aging shot during an exhibition titled “Alive and Artificial” at a hospice in Avignon. Inserting actors into a capacious building occupied by animatronic models and spending as much time on the spatial architecture of the location than on anything resembling a coherent narrative, the short is compellingly watchable despite its inscrutability. And it links Varda to Chantal Akerman, another rebellious female director who would follow her trailblazing lead.

The Exploding Girl (Oscilloscope Laboratories)

SLP: $27.49

Release date: Sept. 7

In the opening shot of The Exploding Girl, lead character Ivy is obscured by a window, asleep in a car while trees blur by in the window’s reflection. It’s a telling preamble, for Ivy remains an obscure character to the very end, her character defined almost solely by her epilepsy (hence, perhaps, the film’s otherwise enigmatic title). The American debut of writer-director Bradley Rust Gray (whose only other feature is the 2003 Icelandic film Salt) follows the 20-year-old Ivy on her spring break sojourn from college, where she returns home and reacquaints with longtime platonic friend Al (Mark Rendell). Her boyfriend, meanwhile, is back at college and can barely be bothered to pick up her phone calls. Nothing much happens, and Ivy is an occasionally frustrating cipher whose emotional canvas remains unpainted. But I admire the film’s photographic naturalism, its dogged resistance toward the traditional grammar of film entertainment and its seemingly unscripted dialogue. Maybe The Exploding Girl is nothing more than a lo-fi, mumblecore variant on the classic teen-movie formula of the girl who should be courting the best friend who cares about her but is tethered to a jerk who doesn’t. But it meanders through this formula lithely and pleasantly.

Grey’s Anatomy: The Complete Sixth Season (ABC Studios)

SLP: $38.99

Release date: Sept. 14

Is it uncool of me to love Grey’s Anatomy? Isn’t it kind of, like, a chick show? And didn’t it jump the shark a couple seasons ago? Malarkey to all. I will concede that its sixth season was far from perfect. The Valentine’s Day episode was unforgivably maudlin, and I lost a modicum of respect for the writers when they went the route of the dreaded flashback episode, progressing nothing in the characters’ stories and instead hashing over irrelevant drama from their pasts. But the sixth season included two of the best episodes in the show’s history. One is the genuinely tear-inducing Thanksgiving-Christmas-New Year’s episode in which Miranda Bailey (Chandra Wilson) confronted her cruel father over his lack of acceptance of her divorce. The other, of course, is the staggering finale, in which a shooter invades the hospital, killing a few doctors and putting other’s lives in grave danger. It’s a more riveting 80 minutes than almost any movie I’ve ever seen.

Release date: Sept. 14

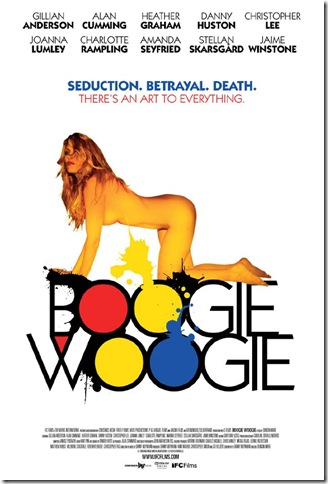

SLP: $17.99

On the heels of recent theatrical releases such as (untitled) and Exit Through the Gift Shop, Duncan Ward’s Boogie Woogie is the latest savage indictment of the superficial modern art world, devouring its shallow, reprehensible subjects as hungrily and callously as those fish feasted on nubile spring break flesh in Piranha 3D. But unlike those other modern art films, Boogie Woogie forgets to make us laugh, failing to realize that a proper satire lampoons its subject with subtle wit, not mere vitriol. Adapted from Danny Moynihan’s acrid novel, there isn’t a single likable, relatable character in Ward’s ensemble of archetypes, from unctuous gallerist Art Spindle (Danny Huston) to haughty collectors Bob and Jean (Stellan Skarsgard and Gillian Anderson) to pompous avant-garde artist Joe (Jack Huston) to cash-strapped collector Alfred (Christopher Lee), whose ultra-rare, titular painting attracts the film’s art-world carnivores like vultures to a carcass. Treating its audience with as much contempt as its characters, there’s nothing of value in this screeching screed aside from the juvenile observation that beyond all the pretentious posturing of modern art, everybody just wants to get laid with many people, and in as many positions, as possible. But it’s hard to take even this message credibly when Ward’s direction is as lecherous as his characters’ philandering libidos. Amanda Seyfried’s sole purpose in the picture appears to be the exhibition of her ass, which is revealed in one crassly titillating angle after another. I thought modern-art porn went out with Warhol?