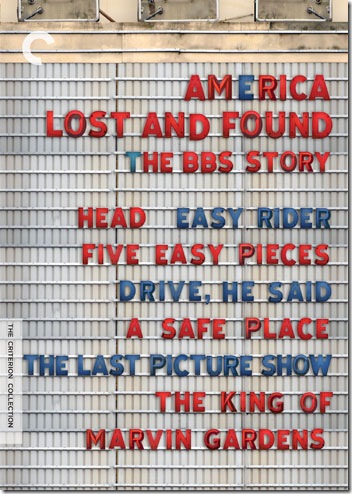

America Lost and Found: The BBS Story (Criterion)

Release date: Dec. 14

Standard list price: $88.99

Released just 11 days before Christmas, Criterion’s America Lost and Found: The BBS Story box set is the holiday season’s ultimate gift to cinephiles. The six films contained in this collection encompass one of American cinema’s most rambunctious, mavericky collectives, which, like the period icons it brought to the screen, burned out in a brazen blaze rather than fade quietly away.

The company in question is BBS Productions, founded at the dawn of 1968 – still early in counterculture revolution that we now refer to as “The Sixties” – by producers Bob Rafelson, Bert Schneider and Steve Blauner. Inspired by drugs, radical politics, art-house movies and John Cassavetes, they sought to remake modern American movies in the image of the changing country they inhabited. They took the stories out of the studios and the moralistic messages out of the stories, cultivating the ambivalent antihero as its stock in trade. And they turned a B-movie writer named Jack Nicholson into an unkempt, unhinged reboot of the matinee idol.

BBS’ proclivity for a different kind of American cinema began with its most zonked-out feature: Head, a self-aware genre mash-up that began as a movie vehicle for television sensations The Monkees and ended up an absurdist comedy and visceral antiwar commentary complete with exploding vending machines, a cameo by a giant-sized sexual Victor Mature and plenty of sexual double-entendre (the movie’s name draws from the creators’ desire to proclaim, on the poster for their next project, “From the studio that gave you Head…”). A drug movie if ever there was one, its G rating remains mystifying.

The BBS team gnawed away at the burgeoning countercultural American psyche for another seven films in a prolific five years, culminating with the great Vietnam documentary Hearts and Minds (not included in this set, but available in a prior Criterion release). The King of Marvin Gardens, the final film in this collection, is a more fitting death knell for BBS anyway. The communist freedom espoused in Easy Rider, BBS’ biggest money-maker, had given way, per the downbeat Marvin Gardens, into a cinema of desperation and constriction, where the failed quest for easy money in the newly developing Atlantic City real estate market made for a sound corollary to the shattered American dreams of a country still mired in its bloodiest conflict.

For the purposes of this article, I’m most interested in the two movies in America Lost and Found that are making their debuts on DVD. It seems almost redundant at this point to wax poetically about Easy Rider and The Last Picture Show; it’s the release of Drive, He Said and A Safe Place that make this box set an event worth celebrating.

The first of just three features ever directed by Jack Nicholson, Drive, He Said is the most underappreciated film in the bunch and also its most inevitably dated. Nicholson was attracted to this adaptation of a successful book, published six years prior to the film’s production, so that he could explore his love of basketball. The story is divided between dual protagonists, both of whom are suffering breakdowns of varying degrees: Hector (William Tepper) is a jaded college basketball star with a hot-headed demeanor whose idyllic affair with a faculty wife (Karen Black) is beginning to crumble. Meanwhile, his activist roommate Gabriel (Michael Margotta) is coming apart to a more disturbing extreme, killing not only his television but shelves full of trinkets, his toilet, his personal relationships and gradually his own mind, which is fine so long is it’ll keep him away from the draft.

Gabriel’s series of theatrical stunts grow more and more destructive, culminating in the liberation of campus test animals following an attempted rape of Black’s character. Drive, He Said a difficult film to watch, despite Nicholson’s assured direction (in one Kubrickian touch, he transitions from a basketball in midair to a piece of food being thrown across the table, matching the previous shot’s trajectory). Part of the reason the movie failed commercially is because it had no interest in offering a romanticized version of the ‘60s. There are no free-lovin’ hippies in this film; the sex, in fact, looks ghastly and unerotic, and Gabriel’s actions are hardly those of the glamorous outsider. If this is the antiestablishment, then the establishment looks pretty appealing.

I was a lot more taken with Henry Jaglom’s A Safe Place (1972), a non-narrative experimental drama initially released to festival audiences with as many jeers as Drive, He Said. Tuesday Weld stars as a woman alternately known as Susan and Noah, who seems to be living a number of lives simultaneously as she begins a relationship with a square suitor (Phil Proctor), enjoys the company of a nondescriptly European park magician (Orson Welles) and rekindles an affair with a possibly psychotic man from her past (Jack Nicholson). She herself seems to be suffering from a mental disorder, reflected in Jaglom’s immersive, subjective intercutting between past, present and future, all commingling in a seemingly random but highly controlled goulash of imagery.

Open-ended and thought-provoking, A Safe Place is an inventive study of a woman’s insanity, anchored by a disquieting sense of art imitating life: Weld was famously unbalanced as a young woman, suffering from alcoholism, a nervous breakdown and a suicide attempt by age 12. Strangely, in his commentary on the film, Jaglom today seems that A Safe Place was an attempt to probe what was really going on inside the female mind, a theory that suggests all women are crazy … perhaps this comes from the fact that Jaglom, by his own admission, was at the time only hanging out with wackos like Weld and Karen Black!

BBS productions ended as unceremoniously as its characters, but this box set provides an essential reminder of how the drive to be different, especially in an industry running on homogeneity, can help change the language of the very form. In this age of apathy (where is our generation’s SDS?), we could use another BBS now more than ever.

Devil (Universal Home Video)

Release date: Dec. 21

SLP: $19.49

This nifty and compact supernatural thriller holds up much better than expected, considering the story and production credits were handled by none other than masturbatory, self-parodic showman M. Night Shyamalan. Thankfully, he relinquished his grubby hands from the director’s chair this time, bequeathing that duty to Quarantine filmmaker John Erick Dowdle, who directs this minimalist material well: A group of five people are locked in a jammed elevator in a Philadelphia skyscraper immediately following a suicide from that very edifice. According to a superstitious technician in the building, this series of events means that one of the people in the elevator is, in fact, Satan, and that the other four are sundry degenerates destined to meet an unruly fate. Devil is not without its clichés; it’s the kind of cheapo B-picture that used to play in ratty drive-ins. Only here it’s been given a slickly shot reboot and a script that handles the story with a commendable degree of realism in terms of how a jammed-elevator situation might actually be dealt with by local authorities (presented in the form of Chris Messina’s recovering-alcoholic cop). The film’s most beguiling sequence happens before the story begins: Dowdle opens the film with a series of mesmerizing crane views of an upside-down Philadelphia skyline, a disorienting prologue that suggests something just ain’t right.

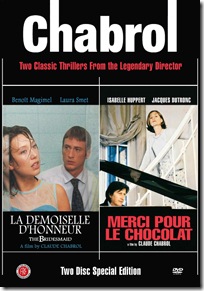

Chabrol: Two Classic Thrillers From the Legendary Director (First Run Features)

Release date: Dec. 14

SLP: $18.99

Claude Chabrol was one of two French New Wave masters to die in 2010 (Eric Rohmer was the other). Often considered, reductively, as the French Hitchcock, Chabrol specialized in wickedly observant thrillers, creating a legacy of 50 films in his wake (his last and latest, Inspector Bellamy, is still playing in limited release). In honor of his passing, First Run recently reissued a couple of his recent films. Not yet as “classic” as the collection’s subtitle makes them out to be, these two features are perfectly representative of Chabrol’s more recent output. Merci Pour le Chocolat, from 2000, is a family saga of secrets and lies, adapted from an American crime novel and featuring a stirring lead performance by Isabelle Huppert as a chocolate company heiress. The Bridesmaid, completed four years later, is even better. A convincing neo-noir about a young man drawn into an attractive psycho girl’s darkest intentions, The Bridesmaid is sexy and disturbing – a much better flick than, say, Fatal Attraction.

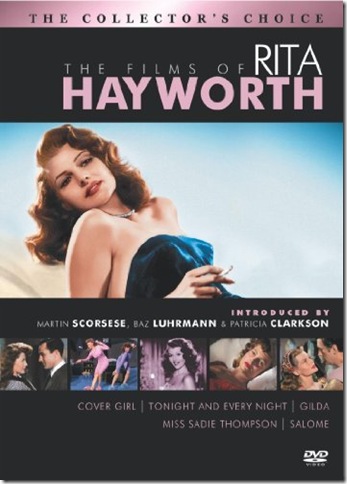

The Films of Rita Hayworth (Sony)

Release date: Dec. 21

SLP: $48.99

Rita Hayworth famously said, “Every man I knew went to bed with Gilda … and woke up with me.” Hayworth is seemingly to be defined forever by her most famous onscreen persona, a vision of sultriness who, more than anyone before or after her, made cigarette smoking look awfully sexy. If she indeed developed as an actress beyond the roles of femmes fatale, sexpots and showgirls, you can’t tell it from Columbia’s new Films of Rita Hayworth box set, but this five-disc collection certainly reminds us why so many, onscreen and off, lusted for her. Of the five movies, only two – Gilda and the splashy Technicolor musical Cover Girl – were previously available on DVD. The other, newly available films are the obscure wartime musical Tonight and Every Night, the W. Somerset Maugham adaptation Miss Sadie Thompson, and Biblical epic Salome.

Salt (Sony Pictures)

Release date: Dec. 21

SLP: $15.99

If my review of Salt isn’t as detailed as some of my others, it’s because I didn’t take a single note while watching it. For many films, this is a sign of being so immersed in the narrative that to divert one’s eyes in favor of the quotidian minutiae of note-taking would be to disrupt, and even insult, the spectacle unfolding before you. Alas, this is not the case with Salt. This time, my absence of mid-film rumination is representative of a film so vacuously middlebrow in its action-movie conventions that it generates nothing worth scribbling. It’s neither an outstanding action film nor an unwatchable hack job. The film, starring Angelina Jolie as a CIA operative who may or may not be a brainwashed Russian spy sent to infiltrate U.S. intelligence system, is this year’s Taken: a breathless, brainless hour-and-a-half-long adrenaline rush, a shot of superfluously plot-twisty cinematic muscle from a director (Phillip Noyce) whose best work has been of the small and suspenseful persuasion (The Quiet American, Rabbit Proof Fence). Roger Ebert’s four-star review of the film this past summer is certainly one of his most curious, to say the least.