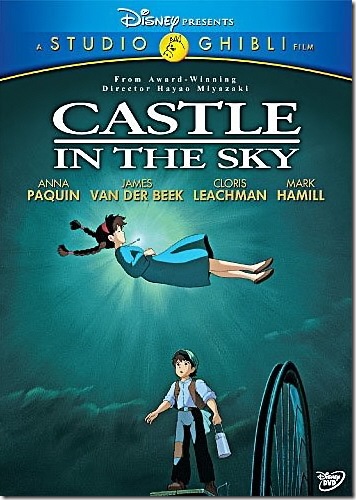

Castle in the Sky, My Neighbor Totoro and Kiki’s Delivery Service (Disney’s Studio Ghibli)

Release date: March 2

Standard list price: $19.99 each

Girls always rule in the films of Hayao Miyazaki, Japan’s top animator and one of international cinema’s most empowering feminist voices. In his four most prominent Western exports – Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle and the recent Ponyo – Miyazaki’s protagonists are girls, from princesses to hat shop workers, whose fantastical journeys change themselves and the worlds around them. In Miyazaki’s tender dreamworlds, there is no such thing as a patriarchal hierarchy. Women aren’t just equal; they’re usually smarter than the men and are more equipped to save the world.

Of course, they’re still adolescent girls, prone to teenage insecurities and harboring fragile tear ducts. This is especially true of three of Miyazaki’s older titles reissued by Disney in two-disc editions this month: 1986’s Castle in the Sky, 1988’s My Neighbor Totoro and 1989’s Kiki’s Delivery Service, each boasting informative new making-of featurettes.

Before delving into the best of these early works, a polite disregard for the one movie that doesn’t stand the test of time or adulthood: Castle in the Sky, Miyazaki’s adventure tale of a princess and a young miner who attempt to find a supposedly mythical sky castle while being pursued by a rickety gang of sky pirates and a corrupt military machine.

Cartoonish in the most infantile sense of the word, Castle in the Sky is silly and predictable, sacrificing storytelling and depth for two hours of almost nonstop action. It lacks the idyllic whimsy of Miyazaki’s later films, and its comic relief is head-scratchingly obtuse. It’s notable solely for its fabulous set designs of the titular castle and other complex edifices, but even these can be seen as phantasmagoric M.C. Escher knock-offs.

My Neighbor Totoro couldn’t be more different in tone and substance, and it’s a welcome change. Centering on two young sisters who endure their mother’s hospital-bound illness with the help of a few friendly forest spirits, Totoro dares to be slow-paced and contemplative from time to time – box-office poison for many children’s works.

Though comparisons to Alice in Wonderland are apt (Miyazaki is an avowed Lewis Carroll devotee), Totoro is less a fantasy than a real-world study of coping. It’s a truly successful family film in that, unlike most of them, it doesn’t talk down to adults or pander to children, striking a deft medium between lightness and darkness, comedy and tragedy.

And finally, in my favorite Miyazaki film, Kiki’s Delivery Service, an adolescent witch’s coming of age makes for an enlightening parable about acceptance, tolerance and self-confidence. Leaving home on her broomstick to live away from her parents for the first time, Kiki settles on a small town that’s seemingly unwilling to accept a witch into its populace. Unaware of any special abilities she may possess, Kiki transforms her known distinguishing talent – her ability to fly – into a delivery service for the town’s residents.

On her routes, she witnesses bountiful kindness and snobbish ingratitude, learning much about the way the world works and battling her insecurities in the process.

Kiki is exactly the kind of character girls will find inspirational, and more than any other protagonist in these films, she anticipates Miyazaki’s later heroines. Peppering his film with dark undercurrents – including an exciting action set-piece surrounding an upturned dirigible – Miyazaki again strikes a concordant balance between whimsy and reality.

Much like the brave-yet-vulnerable, confident-yet-insecure girls at the heart of these pictures, it’s clear Miyazaki himself had yet to blossom into the maturity and sophistication of his later work. The animation is crude, particularly when held up to Pixar’s incomparable standards, and not all of his storytelling conceits walk his now well-worn tightrope of kidvid accessibility and arthouse inventiveness. But two of these underrated titles represent peeks into the visionary looking glass of a future master.

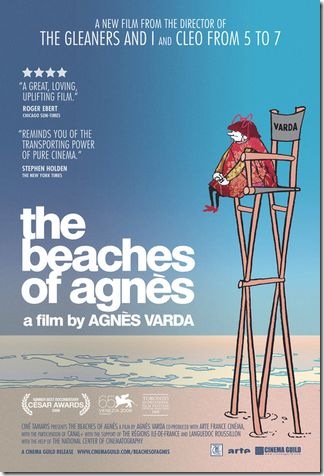

The Beaches of Agnès (Cinema Guild)

Release date: March 2

SLP: $23.99

At 81, Agnès Varda, the director of the 1962 French New Wave classic Cleo From 5 to 7 reinvents cinema once again, this time in the genre of the autobiographical documentary. One of the most overlooked movies of last year, The Beaches of Agnès is a cineaste’s dream from the first frame to the closing credit.

In this literally self-reflexive film, Varda sets up a collection of mirrors, gazes at herself and proceeds to walk backwards through the memories of her life, from childhood to her beginnings as a photographer to her emergence in the New Wave and her romantic relationship with fellow auteur Jacques Demy.

Employing archival film clips, split screens, picture-in-picture, superimpositions and newly filmed documentary diversions, Varda reanimates old film stills and reenacts old memories, all the time with the formalistic boldness and playfulness of someone a quarter her age. The Beaches of Agnès feels every bit like a swan song, and what a lovely, ceaselessly creative way to conclude a life in cinema.

The generous Cinema Guild disc includes an essay by critic Amy Taubin, two shorts about the making of the film and Varda’s magical 2003 short Le Lion Volatil.

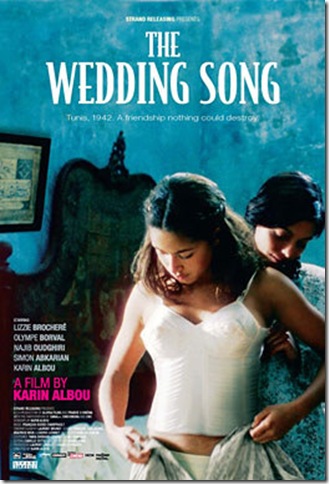

The Wedding Song (Strand)

Release date: March 9

SLP: $24.99

This uninhibited drama set in Nazi-occupied Tunisia centers on a multicultural ghetto and two 16-year-old best friends fixated on marriage: Jewess Myriam (Lizzie Brochere), set to be betrothed to a much older man, and Muslim Nour, whose heart is set on an unemployed man, closer to her age, that her father permits her from marrying.

As outside influences shape the apolitical teenagers’ nascent ideologies, the two girls’ friendship becomes a microcosm for the way Third Reich propaganda divided otherwise stable communities, pitting friend against friend, and certainly Arab against Jew. But Karin Albou’s film doesn’t limit its rage to the stoking of hatred and the Nazi atrocities that followed.

More than any ethnic or religious discrimination, it details the subjugation of women in general with excruciating detail, something that ultimately reconnects the two friends. Its most shocking scene involves a genital waxing, shot in the kind of extreme, gooey close-ups that would never make its way past a Hollywood censor. It’s painful to watch, but it’s the unforgettable backbone of the filmmaker’s aggressive feminist argument.

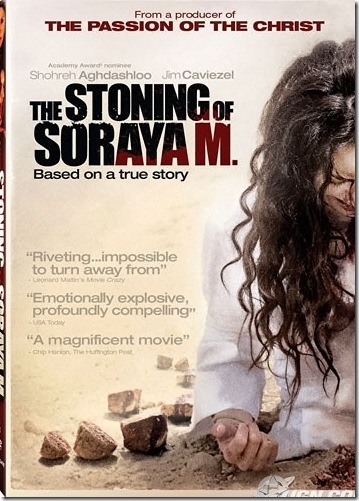

The Stoning of Soraya M. (Lionsgate)

Release date: March 9

SLP: $19.99

This latest, nasty example of torture porn from Passion of the Christ producer Stephen McEveety should have been the moving, enraging women’s picture to end them all. Instead, it’s an exploitative propaganda film whose clunky script and artless direction border on the embarrassing.

A proudly unsubtle attack on the Dark Ages inequalities of Sharia law, The Stoning of Soraya M. is based a 1994 book of the same name about an Iranian woman unjustly accused of adultery (she was found cooking for a friend’s widowed husband) whose protestations to the legislative status quo lead to her eventual stoning at the hands of her ravenous, bloodthirsty community (a climactic sequence offensively shot by director Cyrus Nowrasteh as if it were a multi-angle, action-sports extravaganza).

Designed to provoke gut reactions from guilt-consumed limousine liberals as much as anti-Islamist right-wing xenophobes, this is self-important dreck designed solely for Western export, and it makes me wonder what adventurous filmgoer is cloistered enough to find any of this remotely eye-opening.

John Thomason is a freelance writer based in South Florida.