By John Thomason

The Father of My Children (IFC)

Release date: March 29

Standard list price: $18.99

At just 28, French filmmaker Mia Hansen-Love has shown an Orson Welles-like prodigiousness, already with a short and two features completed and one more in post-production. Given that she’s engaged to established French director Olivier Assayas, has acted in a number of art-house films and is a contributor to the esteemed film journal Cahiers du Cinema, I guess we shouldn’t be surprised at her talent.

But her age is remarkable in light of her breakthrough feature Father of My Children, a film that explores delicate subjects best approached by directors twice her age – parenthood, coping, midlife crises and workaday struggles – all with unvarnished, lived-in verisimilitude.

The father of the film’s title is Gregoire (Louis-Do de Lencquesaing), a high-powered, chain-smoking producer of auteurist, adventurous art films (not unlike Father of My Children) who is raising three girls, two young ones of his own and a teenager from his wife’s previous marriage. Gregoire is a workaholic – his cellphone is practically an extension of his body – who runs a harried, threadbare production company beset by mounting fiscal calamities, from projects that are tanking at the box office to a perfectionist Swedish director who has gone wildly over-budget.

Gregoire finally takes out his financial frustrations in an excruciating, unpredictable act of violence, which, like everything else in Father of My Children, is presented to us with stone-cold, unsentimental matter-of-factness.

This travesty occurs no more than 50 minutes into a nearly two-hour feature, and everything that follows is predicated on this mid-film stunner. In light of spoiling the surprise, I must discontinue the plot description here. Suffice it to say that the moment in question is a monumental example of storytelling subversion on par with L’Avventura and Psycho, and, just as in those classics, we are deprived of preparation for it.

This one action shifts the film’s entire tone and texture; a story that appears to be moving in an elliptical fashion derails itself, careening into a new direction – a kind of post-mortem of the previous narrative. The film’s violent turning point is usually the kind that ends films, not divides them into halves, but Father of My Children isn’t most films.

There is, refreshingly, not an ounce of studio-film sugar-coating in Hansen-Love’s style. Yes, it is a movie about transcending family hardships, but not with melodramatic platitudes, a weeping string section and an unearned happy ending. In fact, the ambiguous ending is anything but happy. It’s less like a pleasurable Hollywood conclusion than one of the melancholy, meandering climaxes from one of Gregoire’s art films.

At the movie’s core is an acute understanding that things don’t always work out, and sometimes we just have to deal with that. It sounds simple, but for a 28-year-old maverick upstart, it’s a sensitive, unusually profound observation.

The Times of Harvey Milk (Criterion)

Release date: March 29

SLP: $21.99

Rob Epstein’s Academy Award-winning 1984 documentary The Times of Harvey Milk doesn’t have any pomp, circumstance or stylistic flash, but when the material is this compelling, there’s no need for any of it: Epstein just lets the extraordinary stock footage speak for itself. Charting assassinated civil-rights leader Milk’s ascent through the San Francisco political establishment, his constant battles against a regressive conservative regime and the details surrounding his murder, The Times of Harvey Milk is an emotionally gripping clip show, aided by interviews with Milk’s closest associates and Harvey Fierstein’s sober narration. Funny, incisive, infuriating and ultimately heartbreaking, it does a far better job than the fictionalized biopic Milk at deconstructing the dog-and-pony show that was supervisor Dan White’s murder trial. The second disc on this exemplary collection includes even more on the White trial, via a reflective panel discussion, plus a rare collection of audio and video recordings of Milk, excerpts from Epstein’s research tapes and several new documentaries. Essential stuff.

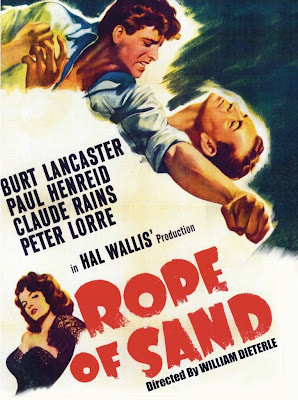

Rope of Sand (VCI Entertainment)

Release date: April 5

SLP: $22.49

Journeyman director William Dieterle directed this fine Saharan adventure story from 1947, notable as the American debut of French bombshell Corinne Calvet. She plays a primitive variation on the hooker with the heart of gold – a sex kitten with a nondescript European accent who is lured into the scheme of a diamond syndicate chairman played by Claude Rains. Calvet becomes the bait for two men – Paul Henreid’s sadistic police commander and Burt Lancaster’s laconic hunter – who had a famous brawl two years prior and now seek a batch of diamonds whose location only Lancaster knows. It’s a lean, occasionally talky story that harbors some fun surprises over the course of its 104 minutes. Mostly, the movie is an opportunity to see great actors honing their personae: Rains is effortlessly dapper and sophisticated, Lancaster memorably brooding but secretly wily and Henreid casually ruthless. And it never hurts when you throw in Peter Lorre playing Peter Lorre.

Thunder in the City (VCI)

Release date: March 29

SLP: $13.49

The noirish title of this 1937 feature is a misnomer: Thunder in the City is actually a romantic dramedy set in the burgeoning, pre-Madison Avenue advertising culture. Edward G. Robinson is a roguish ad executive for a G.E. style industrial manufacturer who, in the film’s unintentionally hilarious opening, is chided by his corporation for his grandstanding ways – including, God forbid, bruiting the company’s name on blimps. His employers seek a more “dignified” approach to advertising, so they banish him to Great Britain, an apparent bastion of classy salesmanship. While weekending in the labyrinthine estate of an affluent dupe, Robinson comes upon a nifty business scheme surrounding an untapped “magnalite” mine. He soon uses his New York-honed showboating acumen to create a national sensation out of the precious metal, while falling for his investor’s daughter. Once you get past the paradoxical concept of dignity in advertising, you can appreciate the movie’s satire, one predicated on glaring cultural and class differences between Yanks and Brits. Robinson is great as a primitive, smarmy antihero, keeping this post-Depression parable alive even as it progresses inevitably into uninspired convention.