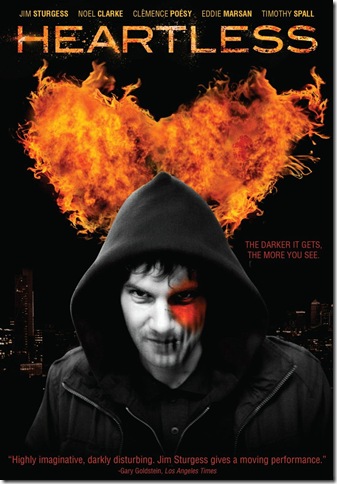

Heartless (IFC)

Release date: April 12

Standard list price: $17.99

A visionary director whose visions are all too infrequent, Britian’s Philip Ridley has made just three films in 21 years, making Robert Bresson look like a workaholic. His audience is tiny and seems unlikely to grow: His outstanding debut, The Reflecting Skin, has never been released on DVD in the United States, and his sophomore effort, The Passion of Darkly Noon, is long out-of-print.

Ridley’s third and latest picture, Heartless, may revive nominal interest in the director’s scant resume, if only because it has the advantage of being available. Unlike his previous forays into humanity’s dark chasms, this gonzo horror comedy resides in a clearly identifiable genre hybrid that has, for years, been growing in popularity. But a Ridley film wouldn’t be a Ridley film if it was accessible to a mainstream audience; simultaneously loud and quiet, blunt and subtle, art-house and grind-house, gruesome and sentimental, Heartless exists within these dichotomies, ping-ponging between tones and textures with the abandon of a director who doesn’t care if the midnight-movie masses like, or even get, his psychotic ramblings.

Like Ridley’s other films, Heartless is a pre-apocalyptic thriller depicting a world crumbling at the seams, physically and morally. Photographer Jamie (Jim Sturgess), forever tainted by a large red birthmark over his left eye and part of his body, prowls the decrepit streets of East London for material. It’s the kind of place that would makes the Fleet Street of Sweeney Todd look like a stroll down Sesame Street. Sharp-toothed demons and rival gangs patrol the metropolis, graffiti plasters every public space and Molotov cocktails erupt on a daily basis. The world is going to Hell, literally it seems: A paranoid, gun-toting shopkeeper rails against society’s descent into Hades, and Ridley similarly alludes to the Devil by having Jamie read Dante’s Inferno and order a drink called the Faust at a nightclub.

When most everyone close to Jamie begins to systematically die, he confronts the source of the terror: A gaunt, scarred Mephistopheles by the name of Papa B (Joseph Mawle), the self-proclaimed “patron saint of random violence.” He agrees to remove Jamie’s debilitating birthmark in return for Jamie’s spray-painting of blasphemous messages on the street – or so he thinks. Devils, obviously, cannot be trusted; the bargain actually forces Jamie to murder someone in cold blood, remove his heart and feed it to Papa B.

Within this grisly, B-movie scenario is the kind of scabrous humor, artistic expressionism and thematic density of a more serious-minded picture. Ridley controls the film’s color palette with painterly exactitude, bathing one scene in darkroom reds, the next in spiritual yellows, the next in placid greens. Everything is propped and set-designed in service to Ridley’s atmospheric rigor, where everyone’s tattoos and birthmarks suggest the branding of otherworldly beasts, and where Christian iconography battles spatially with Satanic forces.

For the comedy, the scenes between Jamie and Papa B are a dry-witted interlude to the best scene in the film: a cameo by Eddie Marsan – the driving instructor from Mike Leigh’s Happy-Go-Lucky – as the devil’s on-site “weapons man,” impatiently issuing mission directives to the flustered Jamie.

Arguably, Heartless falls apart at the end, plunging too deeply into the dubious waters of flashback-induced sentimentalism. But it doesn’t negate the powerhouse of uninhibited emotion that preceded it. The film’s thematic cauldron examines religion, man’s free will, schizophrenia, youth violence and the perennial anxiety over inner vs. outer beauty. The film’s minions of trench-coated, leathery lizards are just the means Ridley is using to touch on life’s most monumental, and unanswerable, questions.

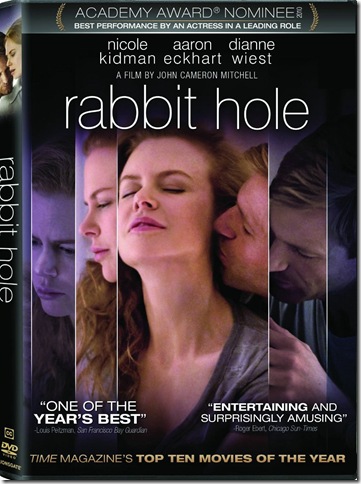

Rabbit Hole (Lionsgate)

Release date: April 19

SLP: $15.49

Hedwig and the Angry Inch director John Cameron Mitchell might seem an unusual choice to helm a film adaptation of David Lindsay-Abaire’s terrific play Rabbit Hole. But the camp-master handles the material – a survey of the emotional wreckage left on a middle-aged couple after their young son is killed in a traffic accident – better than you might expect, directing this chamber piece with appropriate sensitivity and realism. Better yet, screenwriter Lindsay-Abaire clearly recognizes the difference between film and theater, expanding his spartan story with added characters, locations and storylines. The movie isn’t perfect: The Oscar-nominated Nicole Kidman was justly praised as the grieving mother, but costar Aaron Eckhart shoots over the top in the film’s most dramatic scenes, hoping in vain that sheer volume will convey everything. But the only major flaw here is the image itself. Mitchell shot the film on the dreaded but ever-popular Red One digital camera, giving the movie a distractingly ruddy complexion. Judging it purely on its visual aesthetic, Rabbit Hole is one of the great casualties of the digital conversion.

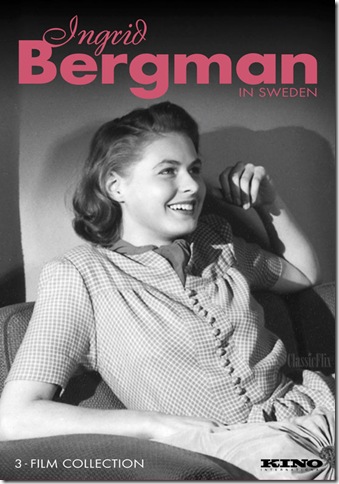

Ingrid Bergman in Sweden (Kino)

Release date: April 19

SLP: $27.49

Though she starred in an impressive canon of Hollywood movies, Ingrid Bergman was always an actress of the world, working for everyone from Hitchcock to Rossellini to Renoir. No nationality escaped her. But before her late ‘30s discovery by David O. Selznick that started her A-list ascent, she was a humble actress in Sweden, making some 11 movies in her native tongue that, today, are barely remembered. Kino’s three-disc box set hopes to change that, bringing two of those films back in print and another to DVD for the first time. The collection includes the original, 1936 version of the romance Intermezzo – whose Hollywood remake a few years later introduced Bergman to American audiences – as well as the facial-disfigurement drama A Woman’s Face and Per Lindberg’s crime thriller June Night.

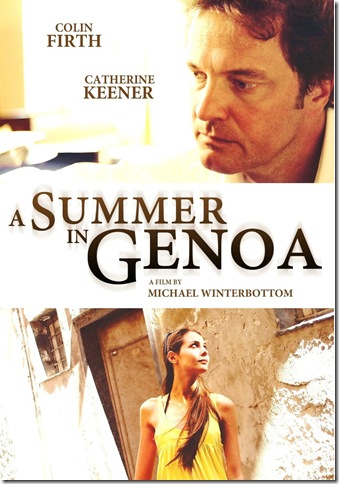

A Summer in Genoa (Entertainment One)

Release date: April 12

SLP: $11.99

Five months after the fatal car crash of his wife, a college professor (Colin Firth) and his two daughters (Willa Holland and Perla Haney-Jardine) spend the titular summer in Italy to assuage their still-palpable grief. Not much happens until Mary, the youngest daughter, begins to see visions of her dead mother (Hope Davis), whose appearances put Mary in danger. Despite its A-list cast – including Catherine Keener as Firth’s ex-flame, who accompanies him on the excursion – and top director (Michael Winterbottom has helmed A Mighty Heart and 24 Hour Party People, among several masterpieces), A Summer in Genoa petered into obscurity after a dismal festival run, and it never picked up theatrical distribution in the United States. From a commercial standpoint, it’s easy to see why – there’s nothing gangbusters about it, and Winterbottom’s meandering, restless camera never gains anything resembling a narrative thrust. But perhaps that’s the point: He wants us, like the characters, to gradually unravel as we lose ourselves in a foreign land. A good effort from a great filmmaker.