For years, I assumed I would simply never have the opportunity to see Skidoo, Otto Preminger’s critically and commercially maligned acid trip from 1968. The film was never even released on VHS and was therefore reduced to a distribution cycle as small as its perceived audience; you could see it at the occasional 35mm revival in New York or Los Angeles, or on a once-in-a-blue-moon screening on TCM.

In other words, Skidoo is a film whose reputation as an exasperatingly dated grasp at the counterculture youth market has, for almost every cinephile, preceded it in an awfully negative context.

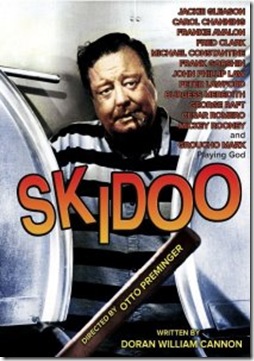

Leave it to Olive Films, today’s top purveyor of marginal ‘70s movies, to finally grant the movie a DVD release (July 19, $22.49). A self-parodic Jackie Gleason stars as “Tough” Tony Banks, a retired gangster unmoored in ‘60s suburbia, chained to a ‘50s wife named Flo (Carol Channing) and daughter Darlene (Alexandra Hay), who’s joined a throng of hippies wearing body paint and traveling in psychedelic buses (cue the copious sitar music).

Tony is soon visited by a couple of his old mob ties, who force him out of retirement on the orders of their boss, a lecherous don named God (Groucho Marx, in his final screen appearance). He is to be sent to prison, where he is assigned to whack a stoolie named Blue Chips (Mickey Rooney), who runs a stock-market racket in luxurious solitary confinement.

While in prison, Tony accidentally imbibes some LSD from his draft-dodging cellmate, and hallucinatory insanity ensues. Outside the hoosegow, Darlene and Flo do whatever they can to track down the missing Tony, even if it means sleeping with the enemy. Oh, and did I mention the film is sort of a musical? Harry Nilsson, who cameos as a prison guard, wrote the film’s catchy, of-the-moment songs (one tune about food is probably a metaphor for socialism), often set to ludicrous song-and-dance numbers that must be seen to be believed.

After watching Skidoo in Olive’s crisp Cinemascope transfer, I found that the initial response makes some sense: It’s obvious Preminger was giving us an instant period piece, destined to feel like yesterday’s film the moment it was unceremoniously ousted from cinemas. Its scenes of LSD consumption shot through the filter of classic slapstick comedy epitomize exactly what Skidoo was, in the eyes of its critics: A prospective youth movie shot by, and starring, a bunch of unhip old guys who never took drugs.

Though an uncredited Rob Reiner was brought in to authenticate the dialogue in the hippie scenes, the characters come off not as real flower children but as every right-winger’s mental image of the perpetually stoned, politically juvenile counterculture.

But to completely dismiss Skidoo would be an injustice to a thoroughly, if uniquely enjoyable, mess that is rife with visual ingenuity and occasionally potent as a satire on American culture.

The opening shot is a classic: Before we see any character, Preminger lingers on a boxy old television, whose channels change every couple of seconds with the impatience of the living room’s ADD-addled viewers. One minute, it’s a John Wayne picture; the next, a Senate hearing; the next, a quack doctor peddling a miracle drug. In one commercial, a dog smokes a cigarette with his human owners; in another ad, an entire family wields guns as a way to bring them closer. It’s not as consistently brilliant as Bob Rafelson’s Head, but in moments like these, it comes close.

For Preminger, who staked his reputation on classic, prestigious studio films – Laura, Anatomy of Murder, The Man With the Golden Arm – Skidoo is more than the “odd film out” in his prolific oeuvre. It represents one of several identity-crisis films that confound auteur critics looking for any shred of directorial distinction. Though it has nothing in common with the films that made Preminger a name, it’s not without technical flourishes that reveal a modernist inspiration. An early split screen that divides the image between a black-and-white flashback and a present-day Technicolor conversation, is especially creative, and kudos to Preminger for going whole hog on Gleason’s first acid trip – a fantasia of hallucinogenic light and sound that culminates in the head of a cigar-chomping Groucho spinning atop a screw base.

This goes beyond where anybody else had gone or would go – J. Hoberman called Skidoo “the most LSD-tolerant movie ever produced in Hollywood” – and it deserves another look, if only for its batty commitment to its own uniqueness.

DVD Watch: July 12: The most exciting release of this week is the audacious, experiential Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (Strand, $25.49 BD, $18.99 DVD), the latest from the hard-to-pronounce Thai auteur Apichatpong Weerasuthakal. It’s a mystifying ghost story unlike any other. Criterion unveils its Blu-ray release of Mike Leigh’s Naked ($27.99), boasting many of the same extras of the DVD release but at a surprisingly more discounted price. This corrosive view of a subterranean England in the mid-‘90s is one of the best British films from that or any decade. Brazil, Terry Gilliam’s prescient satire on the bureaucracy of the future, also gets the Blu-Ray treatment (Universal, $18.99). Lastly, check out James Wan’s Insidious, one of this year’s best horror flicks and one that’s sure to become a cult classic (Film District, $19.99 BD, $16.99 DVD).

July 19: This week is all about Criterion’s release of Satyajit Ray’s The Music Room ($29.99 BD, $21.99 DVD), for the first time since its VHS release. One of the Indian director’s most acclaimed films, released shortly before his renowned Apu Trilogy, it depicts a wealthy man whose life falls apart as his aristocracy crumbles. This well-stocked disc includes a feature-length documentary about the director, functionally titled Satyajit Ray, and a French 1981 roundtable discussion with Ray.

July 25: For this week, I can recommend Jean-Pierre Melville’s Leon Morin, Priest (Criterion, $29.99 BD, $21.99 DVD). Released in 1961 and portraying an altruistic priest’s attempts to “save” a wayward woman, it stands alongside a number of shattering art-house films about faith. Keep it on your shelf next to Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest, Roberto Rossellini’s The Flowers of Saint Francis and the recently issued Of Gods and Men, which Sony released July 5.

I would be remiss if I failed to mention the 29 films that MGM released in late June, to online retailers only, as part of its Manufacturing on Demand series. These stripped-down discs, released on DVD-Rs and without special features or fanfare, will remain the only way to see these obscure titles for some time. They include Budd Boetticher’s tough-as-nails crime film The Killer is Loose ($17.99), the late-period Michael Curtiz thriller The Man in the Net ($19.99), Lindsay Anderson’s long-unseen Red, White and Zero ($19.98), and John Frankenheimer’s Cold War thriller The Fourth War ($19.98).

TCM Watch: Set your DVRs, because July looks like a great month for Turner Classic Movies rarities at inopportune times, starting at 5 a.m. July 12 with Young Winston. Directed by Richard Attenborough in 1972, the film dramatizes the early life of the British prime minister, culminating in his first election to Parliament. It has not been released on DVD, so this is the only chance to see it widescreen.

At 2 p.m. July 15, I recommend checking out a prescient media satire called Slander, from 1956. This one hasn’t been released on any format, and it stars Van Johnson as a children’s TV show host whose career is ruined by a tabloid magazine.

At 2 a.m. July 17, the network will screen Alain Resnais’ Mon Oncle D’Amerique, a renowned drama about three characters who model their lives off of film stars. It was released on DVD but is out of print. At 3:45 p.m. July 19, check out the Delmar Daves Western The Hanging Tree, a Gary Cooper vehicle that has never seen a DVD release.

And Amazon has never even heard of The Carey Treatment, Blake Edwards’ 1972 murder mystery with James Coburn, which screens at 11:15 a.m. July 26. Finally, at 2:30 p.m. July 31, don’t miss Peppermint Frappe, an unreleased 1967 drama by the Spanish auteur Carlos Suara (Spirit of the Beehive).