J. Hoberman famously coined the term “hippie Western” to describe ’70s counterculture films like El Topo. But Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man, released in 1995 and a budget title on Blu-ray as of Aug. 9 (Echo Bridge, $7.99) could be read as a hippie Western for Generation X. Not that the film is necessarily about free love – though we do witness a cowboy receiving oral sex outside a saloon and a pair of Indians enjoying coitus in the woods – or that is advocates drug use; the only substance pined for is legal tobacco.

The comparison is more in the ambience. Even more than other Jarmusch films, Dead Man has a druggy pace. It proceeds with the languor of a bunch of actors and filmmakers on downers who are told to shoot a quick B-picture and end up with a 121-minute spiritual exegesis on the afterlife.

Yes, this divisive film, ignored by audiences and embraced by a few maverick critics (it holds a tepid 58 percent rating on Metacritic), is still crazy after all these years, a holdover from the ’70s auterist autonomy, where the director was king and producers trusted his artistic vision unconditionally. And thank goodness they, in this case Miramax, did trust Jarmusch, because Dead Man is a singular experience as interpretable and poetic as William Blake, whose name is shared by Johnny Depp in the film’s leading role.

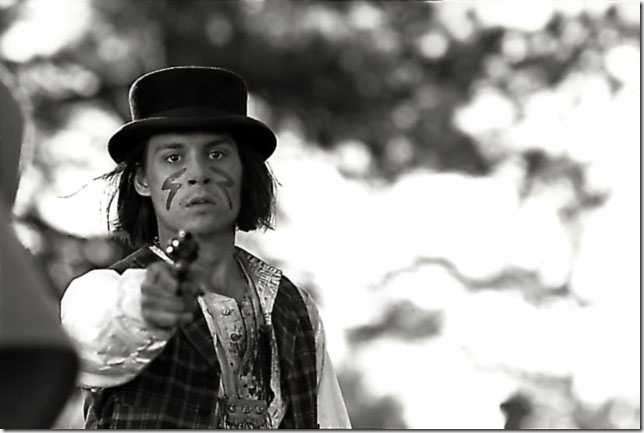

Depp’s Blake is not the legendary English poet; he’s a mere accountant from Cleveland riding a train to California so that he can accept a promised bookkeeping job for an influential machinist. His doom is foretold in a quotation before the film’s first image: He will, eventually, become the dead man of the title, even if the time of his passing is up to the viewer’s interpretation. The first dialogue exchanged in the movie, some six minutes in, comes courtesy of a colorful appearance by Crispin Glover as an illiterate train passenger who further prophesies Blake’s downfall, promising not an illustrious job but the man’s own burial.

Blake ignores the warning, of course, so that Jarmusch can put his own self-reflexive spin on a Western iconography: the “stranger comes to town” scenario. Dismissed by his potential employers, Blake wanders the wild new city like a listless, powerless Gary Cooper, picks up a recovering hooker outside a saloon, shoots and is shot by her vengeful fiancée and becomes an outlaw. On his tail are three guns for hire (Lance Henrikson, Michael Wincott and Eugene Byrd), sent by Robert Mitchum’s John Dickinson, the very man originally set to employ Blake’s services.

Mitchum, in one of his final screen roles, is one several stars who appear in a fun game of Spot the Cult Cameo. Alfred Molina is a devout general-store clerk, John Hurt is a snarky foreman, Gabriel Byrne is one of Blake’s many would-be assassins and Iggy Pop, Billy Bob Thornton and Jared Harris are loquacious trappers Blake encounters on his journey.

Anyway, as composer Neil Young interjects with his occasional shards of “le noise” on the soundtrack, Blake escapes with the help of the hilariously named Nobody (the great Gary Farmer), a mountain of a Native American whose wisdom and shamanic healing methods keep Blake safe through a road-movie, buddy-movie landscape increasingly littered with corpses.

Jarmusch’s most consistently violent film, the death in Dead Man is instantaneous and unceremonious. Blake is not impervious to the carnage, absorbing bullets like a sponge. At what point does he finally succumb to his demise? We’re not entirely certain. There are indications throughout the movie that he may be continuing on as a ghost, his mortal body eradicated by Byrne early in the movie, or perhaps that he was a dead man walking the entire time. But having integrated into Nobody’s Native American customs, his soul is insured a peaceful transition into its next form.

As much as Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt, Dead Man is heavy on what film theorists call intertextuality – the references to previous works that are embedded into the narrative. Western movie iconography, the histories of the actors, the black-and-white nature of the luminous cinematography, the quote that opens the story and the real William Blake’s oft-referenced poetry – all of these things are essential to and inextricable from Jarmusch’s own contributions.

The latter of these may be the key to the film’s position on life after death. Dead Man may be an extended two-hour death spiral, but Blake’s very name and his embrace of a new, violent poetics suggests the immortality of art and poetry, his mortal life giving way to a spiritual transcendence that can never be quashed. Pretty trippy, eh?

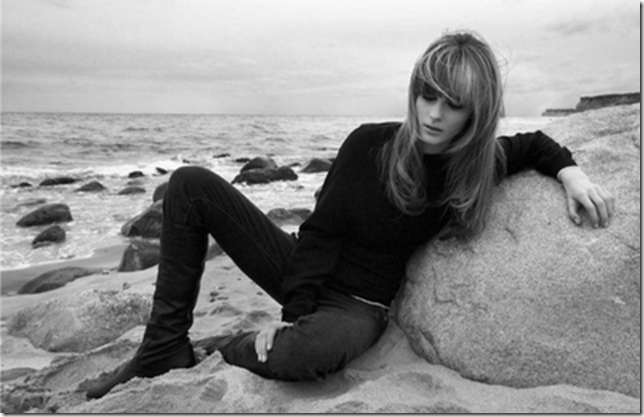

Aug. 16: The highlight of this week is Roman Polanski’s pitch-black comedy Cul-de-Sac, from 1966 (Criterion, $19.99 DVD and $27.99 Blu-ray). Donald Pleasance and Françoise Dorléac play the occupants of a beachfront castle invaded by a criminal and his dying partner, and eccentric happenings ensue. One of the last remaining Polanski features to receive a DVD release, it’s perhaps easy to see why: With its absence of likable or relatable characters, Cul-de-Sac is considered a hard pill to swallow. But, like The Fearless Vampire Killers, it’s a cult favorite among his fans. Extras include Two Gangsters and an Island, a documentary about the making of Cul-de-Sac, a 1967 interview with Polanski and a new essay by critic David Thompson.

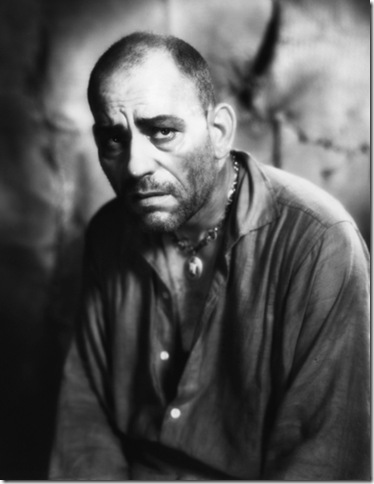

This week also sees the domestic home-video debut of David Holzman’s Diary (Kino, $20.99 Blu-ray, $26.99 DVD). Before he became a mainstream director-for-hire, Jim McBride made this influential and unique parody of the cinema verité aesthetic, centering on a guy intent on filming every little bit of minutiae in his life – and the trouble this gets him in. Prescient in its presentation of an exhibitionist man shattering the designation between the private and the public, this is an essential film. This special-edition disc also includes McBride’s 1961 feature My Girlfriend’s Wedding as well as two of his short films.

Also on tap for this week: The Blu-ray debut of the Coen Brothers’ inexplicably popular The Big Lebowski (Universal, $22.49) and Criterion’s reissue of The Killing ($21.99 DVD and $22.49 Blu-ray), one of Stanley Kubrick’s earliest and most accessible thrillers, loaded with exciting extras include a remastered transfer of Kubrick’s 1955 noir Killer’s Kiss.

Aug. 23: Brazilian cinema takes center stage on a four-film box set by First Run Features titled The Best of Global Lens: Brazil ($29.99). Titles include the World War II road movie Cinema, Aspirins and Vultures, the political epic Almost Brothers and the modern silent film Margarette’s Feast.

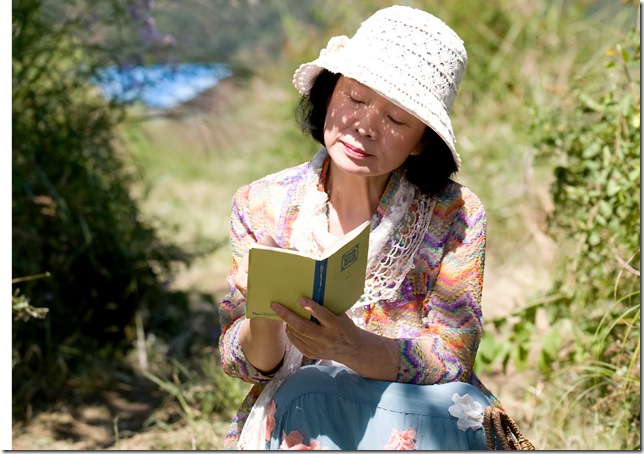

Also, check out two titles from South Korean auteur Lee Chang Dong: Poetry (Kino, $29.99 DVD and $20.99 Blu-ray), one of 2011’s most critically acclaimed films, about an Alzheimer’s-suffering pensioner’s self-actualization thanks to a poetry class, and Secret Sunshine (Criterion, $25.99 Blu-ray and $19.99 DVD), a drama about grief released four years prior. Also of interest is Road to Nowhere (Monterey, $31.49 Blu-ray and $24.49 DVD), a Lynchian movie-within-a-movie thriller from the cult director Monte Hellman (Two-Lane Blacktop) – his first feature in more than 20 years.

Aug. 30: This week is simply a bounty of riches; were I to trumpet them all, I would need this entire column space. A few of the most staggering releases: The Coen Brothers Blu-ray collection (Fox, $47.99) compiles Blood Simple, Raising Arizona, Miller’s Crossing and Fargo, and The Complete Jean Vigo (Criterion, $27.99 Blu-ray and $21.99 DVD) compiles the French director’s previously released masterpiece L’Atalante with his just-as-impressive shorts A propos de Nice, Taris and Zero for Conduct. Ingmar Bergman’s 1976 Face to Face finally gets a DVD treatment from Olive Films ($26.99), Universal unveils a limited archive release of Jack Cardiff’s The Incredible Shrinking Man ($14.99) and Cinema Guild issues, for the first time, Agnès Varda’s 1975 documentary Daggeroutypes ($29.95). Whew! Happy renting.

TCM Watch: Throughout August, TCM will be showcasing the work of an iconic star each night of the month. The network will pay homage to Orson Welles all night Aug. 8, with rarely screened – though easily rentable – features such as Mr. Arkadin (6:15 p.m.) and The Lady From Shanghai (2 a.m.). But the real treat here is a 4 a.m. showing of The Immortal Story. This late period, 58-minute Welles feature, released in 1968 and made for French television, is the master’s only movie shot in color. Welles costars with Jeanne Moreau in a story about a wealthy European merchant who plays games with the lives of a sailor and a beautiful young woman. But really, who cares about the plot – this is a forgotten Welles film, unavailable on home video in the States, given a new life and a new audience.

At 2:45 a.m. Aug. 13, as part of a James Stewart night, check out Tim Whelan’s The Murder Man, a well-received, though never released on video, ’30s crime film with Spencer Tracy as a newspaperman specializing in murder cases who becomes the subject of a murder case himself. Sounds to me like Samuel Fuller meets Alfred Hitchcock.

Classic horror lovers won’t want to miss the Lon Chaney tribute all day Aug. 15, featuring a number of unusual silent films. The evening concludes with five films Chaney made for director Tod Browning (of Freaks fame), beginning at midnight and running until the wee hours. They included the unreleased-on-video West of Zanzibar, about a mad ruler of a jungle monarchy; Where East is East, about an animal trapper in Indochina; and the particularly scarce and uncompleted London After Midnight, about vampires suspected of murder (isn’t that kinda what vampires do?).

On Aug. 16, catch a few rare gems with the star of the night, Joanne Woodward, including The Sound and the Fury (10 p.m.), Martin Ritt’s adaptation of the Faulkner novel; and The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds, Paul Newman’s complicatedly titled adaptation of Paul Zindel’s Pulitzer-winning play.

A Burt Lancaster tribute on Aug. 25 includes the only John Cassavetes film not released on DVD in the U.S. It’s called A Child is Waiting (6 p.m.), and it’s about an emotionally fragile woman (naturally) who becomes a teacher to handicapped children. Gena Rowlands and Judy Garland star alongside Lancaster.

These are only a few choices in a well-stocked month of star-themed days and nights. Other actors celebrated throughout August include Montgomery Clift, Jean Gabin, Carol Lombard and Humphrey Bogart.