American director Alex Cox remains most famous for the first two films he ever made: 1984’s Repo Man and 1987’s Sid & Nancy. He’s continued to be active for more than two decades since, though you wouldn’t know it from the lack of distribution his films have received – Cox seems content with making cult movies for microscopic audiences.

A crueler critic might suggest that he deserves his lot in life as middling obscurist, given that most of his recent works have been revisions or sequels to his previous films (Repo Chick, Straight to Hell Returns) or hommages to other people’s films (Searchers 2.0).

But this time, Microcinema, which has been handling most of the worldwide DVD distribution for Cox’s recent movies, has plumbed the director’s archive for a feature made during his artistic peak – 1991’s Highway Patrolman (Nov. 15, $22.49) – and it’s a strong enough film to merit a reconsideration of some of Cox’s more unsavory features to come.

Conceived in Los Angeles but shot in Mexico from a Spanish-language script by Lorenzo O’Brien, the genesis of Highway Patrolman reveals that, even in ‘91, Cox had to flee the constraints of Hollywood to make the art he wanted (he would later shoot a TV movie in Japanese). The result is unlike any cop movie I’ve ever seen, save for the 2002 American indie Evenhand, which owes a debt to Cox.

In carefully composed single takes that plant characters firmly in time and space, Cox follows young cadet Pedro Rojas (Roberto Sosa) from the moment he receives his badge and gun through the day-to-day grind of police work in the arid deserts and dusty streetscapes of Mexico City. Time, inexorably, marches on, in episodic fashion: He discovers that bribery is the only way things get done in his corrupt jurisdiction; he gets married but finds himself frequenting a prostitute to relieve the stress of his life; he drives a broken-down jalopy until it dies on him shortly before a tragedy, leaving him with a gaping chasm of guilt. All the while, the ghost of his absent, disapproving father looks down on him (literally, in one surreal scene), his melancholic presence awash in pathos.

At the time of its release, L.A. Weekly called Highway Patrolman “Robert Bresson with a rock ‘n’ roll pulse,” which is a clever description, but I don’t see either of these influences on the screen. The film, and the patrolman’s existential job, is more like free jazz that meanders, unrooted but prone to occasional returns to structured cohesion. We grow so inured by the film’s workaday, slice-of-life ennui that its moments of violence hit us, and Pedro, with the sudden and brutal impact of an oncoming train.

As the danger increases and more blood is shed, Highway Patrolman begins to borrow the syntax of two gritty genres: the war film and the Western. Like the former, Pedro navigates an environment that increasingly resembles a battlefield, complete with a moment in which a colleague dies in his arms. And like the latter, Pedro starts to resemble Clint Eastwood’s Man With No Name (Cox is a student of spaghetti Westerns) – a rogue figure operating in an apparently lawless world – whose (anti)climactic moment involves a rock-obscured shootout with another lone gunman.

All of which goes a long way to distinguish Highway Patrolman from the machismo-laden, reductive tradition of the Hollywood cop as valiant, justice-dispensing hero. Cops are flesh-and-blood humans like the rest of us, and, like soldiers, they’re sometimes scared and confused.

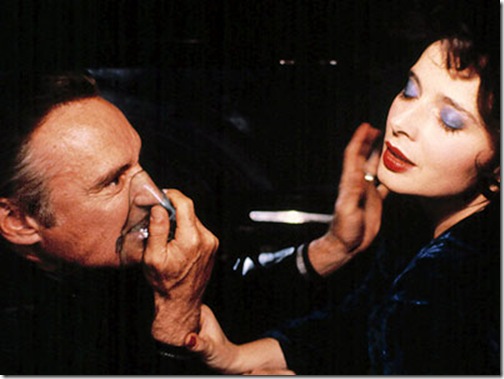

DVD Watch: Nov. 8: This a great week for cult and mainstream classics alike making their Blu-ray debuts, with none more exciting than Blue Velvet (MGM, $15.99). The selling point for this edition of David Lynch’s twisted masterstroke is the 50 minutes of newly discovered lost footage available as a bonus feature. The other extras are not new to this disc, but it’s always nice to see Siskel and Ebert’s legendary review of the film; Ebert comes off as a moral crusader and Siskel the critical adult who can separate the art from his emotions. Also, don’t miss The Collector (Image, $12.99), William Wyler’s atypical psychological thriller from 1965; Fanny and Alexander (Criterion, $40.99), Ingmar Bergman’s sweepingly personal holiday masterpiece; and To Die For (Image, $12.99), Gus Van Sant’s bracingly effective 1995 dark comic vehicle for Nicole Kidman.

Nov. 15: This week, Infernal Affairs (Vivendi, $15.99), the Korean actioner that inspired The Departed, makes its premiere on Blu-ray. Some assert that it remains superior to Martin Scorsese’s Best Picture winner; judge for yourself in shimmering hi-def. Also, don’t miss Blu-ray debut of Krzystof Kieslowski’s Three Colors Trilogy (Criterion, $55.99 or $41.99 for the DVD set), one of the reigning achievements of ‘90s art cinema and three of the finest performances that Juliette Binoche, Irene Jacob and Julie Delpy ever gave. It’s a film where color really matters, and, this side of a newly struck 35mm print, those colors should never look better. This week also finds Paramount bowing the Blu-ray debut of George Cukor’s adaptation of My Fair Lady ($19.99).

Nov. 21: Things start to get quiet leading into the holidays, which is surprising, but there are still a couple of must-see titles hitting shelves over the next two weeks. Today sees two silent classics from D.W. Griffith receiving the Blu-ray polish from Kino: the unassailably important Birth of a Nation ($23.99) and 1920’s underrated Way Down East ($21.99). Elsewhere, Criterion unveils a release of Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men ($27.99 Blu-ray, $17.99 DVD) that includes new and archival interviews, a video essay on the story’s transition from stage to screen, and even Frank Schaffner’s 1955 TV version of the play.

Nov. 28: Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (MPI, $18.99 Blu-ray and $24.99 DVD – yes, the DVD is more expensive) is one of the year’s best films, but it may lose some of its entrancing luster if you don’t have a 3D television. Reel Injun, a hit at last year’s South By Southwest festival and directed by Neil Diamond (not that Neil Diamond) is a look at Hollywood’s depiction of Native Americans from the silent era through the independent films of the ‘00s. Clint Eastwood and Jim Jarmusch are among the interview subjects.

TCM Watch: At 4:30 p.m. Nov. 14, I wouldn’t miss I Married a Witch, an English-language fantasy from Rene Clair about a 17th-century witch who returns to modern times to plague a descendent of her persecutor. It’s not available on DVD in America. For the most part, November marks an interesting month for noir and crime films. Chase a Crooked Shadow (8 p.m. Nov. 16), also unavailable on DVD in the States, is a tense little thriller from 1958 with Richard Todd and Anne Baxter.

Nov. 22 is a great day to bookmark; first, check out Terror on a Train (6 a.m.), a 1953 Glen Ford thriller about a bomb on a train that sounds like an inspiration for Source Code. It hasn’t been released on home video anywhere. Down Three Dark Streets (3:15 p.m.), from 1954 and currently available on a limited-edition MGM disc, is a stylish detective story with interweaving narratives; and 1955’s Joe Macbeth (4:45 p.m.) may be the most unusual of them all, a retelling of Macbeth in a modern gangster setting that hasn’t been released on any video format.

Other interesting screenings of films not on DVD include Sam Fuller’s western Run of the Arrow (4:30 p.m. Nov. 21) and Arthur Hiller’s ‘60s comedy Penelope (10 a.m. Nov. 25), with Natalie Wood and Peter Falk.