Bravo, once again, to maverick distributor Olive Films for releasing yet another brave, cinephilic film for a microscopic but dedicated audience.

For many of my movie-obsessed brethren, the release this month of Jean-Luc Godard’s Histoire(s) du Cinema ($44.99) is the most exciting home-video news of the calendar year, a monumental achievement in experimental self-reflection and the perfect Christmas gift for the jaded avant-gardist.

Histoire(s) du Cinema is an eight-part video series, with the individual movies running between 23 and 52 minutes. Godard filmed the first two (which are probably the most impressive) in the late 1980s and finished the others in 1997 and 1998. The films comprise the story of cinema’s history through Godard’s unconventional lens; for Godard, this history is decidedly nonlinear and global, with images from Griffith and Murnau rubbing elbows with Hitchcock, Rossellini and Godard’s own New Wave classics (and the occasional, jarring blip of hardcore pornography, of which no complete history of moving pictures can do without).

The Histoire(s) videos – bearing subtitles like Fatal Beauty, The Coin of the Absolute and Control of the Universe – are essentially essay films more fit for the endless loop of museum exhibition than the straightforward projection system of movie theaters. You can approach them from the beginning, middle or end and appreciate them equally, which is appropriate for a director who famously said, “A story should have a beginning, middle and end … but not necessarily in that order.”

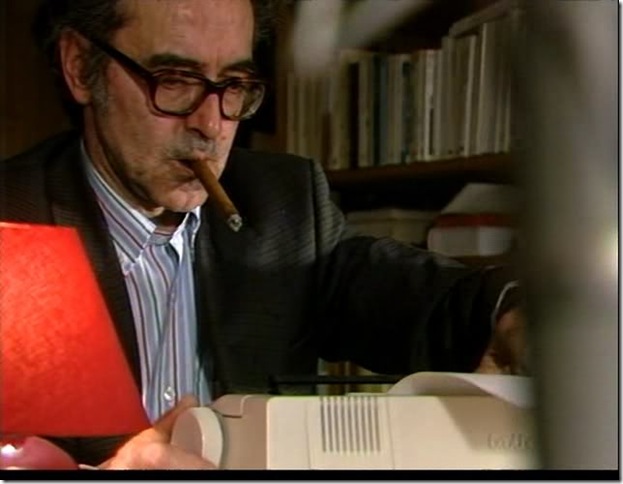

Godard himself appears in several of the videos in static shots, whether he’s cutting film in a projection room or flipping through film-theory books, and he’s perpetually puffing on a stogie. But mostly, these works are comprised solely of film clips – some still, others moving – jumbled together with other movie images in a state of epileptic intercutting, and overlaid with seemingly unrelated text and more seemingly unrelated narration from Godard himself. Occasionally, we get an evocative score from the likes of Bernard Hermann, Beethoven, Leonard Cohen or Tom Waits, yet another element adding to the audiovisual clutter.

In this continuous status of information overload, the film clips rarely last longer than a few seconds; this is cinema at its most ADD-like. Godard deploys slow-motion effects on standard-speed movies and creates irises around images where none exist, manipulating iconic art-house visions to fit his agitprop history. This flurry of joy expressed for Godard’s most cherished artistic medium is inspiring, even if some of his messages are so personal as to be inscrutable (“A 35mm rectangle saves the honor of reality.”).

And it’s all the more impressive given that it was made in a pre-Internet, pre-Final Cut Pro age. The best corollary I can conjure for Godard’s sample-heavy remixes is the trend of mash-up music created by deejays like Danger Mouse, Girl Talk and Avalanches, and Godard, in typical trailblazing fashion, beat them to it by decades.

Occasionally, Godard corralled big-name actors and critics for this series. In part three, titled Only Cinema, he has a conversation with influential movie writer Serge Daney about the French New Wave and its role in the history of movies; it’s the only approximation of a coherent conversation in the 266-minute totality of the project. He uses Julie Delpy and Juliette Binoche in two of the other videos, but the results are not particularly exciting.

He has them read obscure poetry, echoing his employment of Woody Allen in his revisionist film version of King Lear. Their star power is demystified, as it should be, leaving us to focus solely on the film clips and the relationships and contexts Godard creates through their collisions.

An overriding obsession running through these videos is cinema’s origins and its distinction from painting, photography, theater and literature, and some of the most moving passages detail the medium’s role in fostering escapism, developing mind-numbing television programs and colluding in war propaganda.

Godard’s narration and editing choices may wander now and then into dense thickets of esoterica, but when he’s at his most focused, he’s a master of polemical expressionism. He ends the last video on an apocalyptic dissection of a world overrun by global, abstract tyranny, while finding pleasure toiling in a world fraught by “inexorable decline.” Say what you want about Godard’s increasing inaccessibility in the 20th and early 21st centuries, but one thing is for certain: The guy certainly hasn’t mellowed.

DVD Watch: Dec. 6: There may be no better gift for the sophisticated cinephile on your list (can I be that person?) than Design for Living (Criterion, $35.99 Blu-ray, $26.99 DVD), Ernst Lubitsch’s pre-Code 1933 sex comedy, adapted from a Noel Coward play, about a woman and two men who decide to live together in a “gentleman’s agreement” to discover which of them will end up together. It’s Gary Cooper and Frederic March fighting over Miriam Hopkins with a risqué suggestiveness on which the moralistic Hayes Code would soon clamp down. The bonus features are excellent, including a Lubitsch short film taken from the 1932 omnibus movie If I Had a Million and a British television production of the play Design for Living.

Just as exciting is the home video release of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Medea (Entertainment One, $19.99 Blu-ray, $16.99 DVD), one of the Italian auteur’s most aesthetically rigorous films. A nearly wordless take on the oft-staged Greek epic, it’s remembered as the only film ever made starring opera diva Maria Callas. Also, check out a pair of modern French actioners that harken back to the ‘70s American genre pictures of Frankenheimer and Friedkin: Point Blank (Magnolia, $21.99 Blu-ray, $15.99 DVD) and Rapt (Kino Lorber, $31.49 Blu-ray, $26.49 DVD).

Dec. 13: Speaking of John Frankenheimer, one of his most unusual films arrives in DVD from Shout! Factory this week. 99 and 44/100 Percent Dead ($15.99) – one of the most cumbersome movie titles in film history – is an underrated, blackly comic gangster flick from 1974 starring Richard Harris. It’s packaged in a double-feature DVD alongside The Nickel Ride, another 1974 crime film from Robert Mulligan. On the newer front, Daddy Longlegs (Zeitgeist, $26.99) is a critically acclaimed independent dramedy by first-time feature filmmakers Ben and Joshua Safdie, about a manic, irresponsible but tragically human father and his sparse relationship with his two young sons.

Otherwise, this is a great week for Blu-ray reissues of modern and classic titles, including Vincente Minnelli’s lavish (and occasionally subversive) musical masterpiece Meet Me in St. Louis (Warner, $25.99), the kinetic art-house hit City of God (Lionsgate, $14.99), Peter Jackson’s cult film Heavenly Creatures (Miramax Lionsgate, $14.99) and Todd Haynes’ eye-popping, fictionalized account of the glam rock movement, Velvet Goldmine (Miramax Lionsgate, $14.99).

Dec. 20: This week marks the home-video debut of one of the year’s most enjoyable movies, Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris (Sony, $22.49 Blu-ray, $17.99 DVD), as well as the Blu-ray premiere of William A. Wellman’s Nothing Sacred (Kino Lorber, $21.99), a 1937 journalism comedy with a brilliant Ben Hecht script and a characteristically wonderful lead performance from Carole Lombard.

TCM Watch: A tribute to tough, hard-boiled studio director Edward Dymytrk on Dec. 10 includes two rarities: Obsession (10:15 p.m.), a thriller about a psychiatrist plotting revenge on his wife’s lover; and Till the End of Time (3:45 a.m.), a Robert Mitchum vehicle about returning war veterans that sounds remarkably similar to The Best Years of Our Lives, released the same year.

At 8 p.m. Dec. 14, as part of a lineup of rare films dedicated to the preservation efforts of the George Eastman Film Archive, TCM will present the world television premiere of Stanley Kubrick’s unreleased debut film, the antiwar drama Fear and Desire. This is a big deal. Ditto to John Ford’s The World Moves On, a 1934 reflection on the Great Depression that runs at 2:45 a.m. that night.

Lastly, at 7:15 a.m. Dec. 21, check out The Chapman Report, a George Cukor comedy with Jane Fonda, Shelly Winters and Claire Bloom that hasn’t seen a DVD release.