The View From Home may have seemingly taken a couple of months off, but our intrepid cineaste never stopped watching movies. Here are some highlights (and a couple of lowlights) to hit Blu-ray and DVD shelves in September and October.

For almost 10 years, 1977’s The Devil, Probably (Olive, $22.46) has been on my personal short-list of Holy Grail films never released on DVD, and boy, is it worth the wait. In the penultimate film by French minimalist Robert Bresson, Antoine Monnier plays Charles, a fey navel-gazer whose feminine looks approximate an Enlightenment poet crossed with a roadie in a grunge band. Like a character in a Rohmer film, he’s torn between two girls, but like a character in an Antonioni film, he’s emotionally adrift in a soul-crushing industrialized world, and his tight circle of friends is not enough to prevent an inexorable drift toward his own demise (this is no spoiler; the information is revealed by Bresson in the film’s very first image).

As always with Bresson, the economy of his style is unparalleled; not a shot is wasted, and even a montage of bus riders’ ingress and egress is stylistically thrilling to watch. But this plotless meditation on youthful malaise is arguably more rigid and claustrophobic than most Bresson films. His overarching theme of characters trapped in prisons plays out here in the director’s precise framing devices, suffocating and compartmentalizing Charles and his companions in a procession of slim doorways, stairwells, subways and cramped apartments. The square 1:37 aspect ratio, employed while the rest of the movie world was filming in widescreen, further enhances Charles’ inescapable enclosure. And what makes The Devil, Probably all the more haunting is that Bresson seems to share his protagonist’s suicidal thoughts, painting a lucid picture of a world in decline, caught in the unsustainable throes of pollution, sewage, food poisoning, the eradication of wildlife and the perennial threat of nuclear annihilation. There’s nothing quite like the film’s signature sequence: a devastating montage of impressive trees felled at their roots – sacrifices at the altar of progress.

The most creative vision in the comedy Lola Versus (Fox, $24.99) occurs in its opening minute, when Greta Gerwig’s Lola imagines herself swept away in an idyllic beach. But then when a wave washes ashore, the beach is suddenly flooded with dildoes and stilettos, symbolic detritus Lola dodges like a soldier dancing around landmines. The rest of the movie is unalloyed, unambitious boilerplate. The 29-year-old Lola is promptly dumped by her seemingly perfect fiancée (Joel Kinnaman) three weeks before the wedding, prompting a soul-searching quest to discover love – and herself – before her 30th birthday.

Gerwig is forced to fumble, fluster and engage in a procession of stupid sexual dalliances in a manner that is below the intelligence of both her character and Gerwig as an actress. That she still manages to charm and class up the joint says a lot about her considerable skill, because she’s surrounding by rom-com clichés, most annoyingly Zoe Lister Jones’ impossibly eccentric best friend, with her vulgar non sequiturs (“I’m going to go wash my vagina”) and offers of marijuana-laced candy she obtained overseas. If any of these creations start off as real people, they quickly become movie characters, or rather sitcom characters, as writers Jones and Daryl Wein load the script up with jokes every 15 to 30 seconds, trying desperately to stay precious and “with it” – note the references to Glee, Cee Lo and GMO food within the first 10 minutes. False notes abound in this nadir of post-Bridesmaids chick-flick raunch.

The title character of Vittorio de Sica’s Umberto D. (Criterion, $34.65 Blu-ray) survives, barely, on small favors while suffering life’s multitude of indignities. Dressed in funereal black, with only his devoted mutt by his side, he is stripped of his pension, cheated by his landlady and evicted from his ant-infested apartment, forced to eschew pride and beg for change on the streets of Italy. His one human companion, a teenage girl who cleans the apartment complex, doesn’t have it much better: She’s been knocked up by one of two men, and she’s certain she’ll be fired when the fascist landlady discovers this information. This humbling postwar classic takes a simpler, more domesticated approach than Roberto Rossellini’s brutal war films from the same period, but the spirit of post-battle-scarred rage is ever-present. The film moves very slowly by today’s standards, but Umberto D. is a more complete movie for de Sica’s deliberate lingering on the squalid lives of the proletariat. De Sica has always been a better visual stylist than he is given credit for in the Italian Neorealist movement, and the shadows, zooms and use of music, reflections and visual obstructions reveal a studio talent shackled to the plein air. Extras on this gorgeous new transfer include a 50-minute documentary about de Sica’s career.

Oslo, August 31st (Strand, $15.13), is, as its title suggests, a day-in-the-life film set largely in the Norwegian city, and it’s a kindred spirit to Louis Malle’s stark 1957 drama The Fire Within. It dramatizes – or, rather, de-dramatizes – drug addict Anders’ daylong leave from his rehabilitation center, for the purpose of a job interview. Along the way, he reconnects with an old friend – a formerly nihilistic chum who is now a drugless, passionless husband and father – and has an uncomfortable run-in with his sister’s friend, because his sibling isn’t ready to see him yet. All the while, he leaves pitiful, unreturned voice mails to an ex-girlfriend now living in the States. Anders is a cog that doesn’t fit into the machine of life. His world view is crushingly defeatist and frequently suicidal, and his friends don’t – can’t – understand his despair. The film shows the constancy of addition, like an insect forever buzzing around the brain for another fix. This all sounds hopelessly depressing, and for some, it may be. But I found Oslo, August 31st a rapturous example of poetic realism, with dialogue that almost sounds too authentic to be scripted. The words and the performances hit home with resounding accuracy, commenting with ageless wisdom on maturity, humanity and the necessity of change amid life’s inexorable progress.

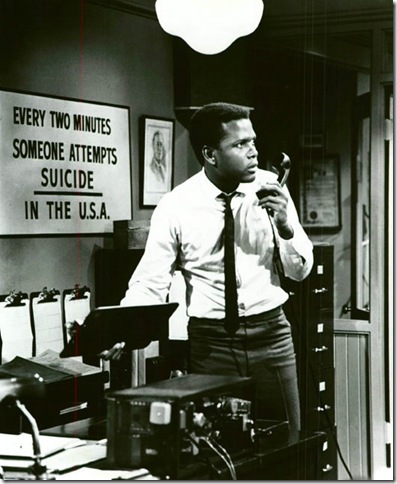

A dreary feature-film debut from the late Sydney Pollack, 1965’s The Slender Thread (Olive, $19.99 DVD, 28.83 Blu-ray) is a curious hybrid of domestic potboiler and spartan suspense flick, with Sidney Poitier as an untested college volunteer at a crisis call center and Ann Bancroft as the suicidal woman who dials his number. The action plays out more or less in real time, albeit with copious flashbacks into the past few weeks of Bancroft’s life and the events that led her to overdose on barbiturates. Bancroft is very good, but the best moments in the film are Poitier’s – alone, for the most part, sweaty, and way over his head, gripping the phone for dear life while trying to convince a stranger to provide her address, while he attempts to surreptitiously trace her call. Pollack never intercuts shots of Bancroft while focusing on Poitier, wisely choosing to isolate the two characters in the viewer’s mind as well as the film’s space. He, and we, are both working with the same information, delivered by an elusive, disembodied voice. I could have done without the superfluous zooms and over-the-top melodrama, but Pollack was clearly learning to discover his voice. Dig the cool jazz score from Quincy Jones.

The Game (Criterion, $24.99 DVD, $29.99 Blu-ray) is, and may forever be, the dark horse in the filmography of David Fincher. If Fincher is best exemplified as the purveyor of a brand of brutal auteurist elegance frequently at odds with the mainstream Hollywood product upon which he is summoned to direct, The Game may be the most extreme example of the Fincher polarity between artist and entertainer. When I saw The Game in 1997, I was all of 15 years old, and I dismissed its ludicrous plot: A self-absorbed business tycoon played by Michael Douglas is given a gift certificate for a life-changing “game” courtesy of a shadowy, acronymic corporation, only to have his entire life upended; free will is stripped away, everything he encounters is an illusion, and death seems the only escape, until one of the ballsiest deus ex machinas in movie history gives the “Game” away.

What seemed like a silly trifle to my uneducated teenage eyes now seems like a wickedly sharp satire on the Hollywood Dream Factory – a self-reflexive meta-commentary on the ridiculous plots we’ve been conditioned to swallow. Douglas symbolizes us as spectators, navigating the artifice of labyrinthine plots. Rarely has a director’s mechanisms of manipulation been laid as bare as it is here (though Michael Haneke’s Funny Games, released coincidentally the same year, seemed to be up to the same game). That Fincher accomplishes this with such a confident and beautiful mise-en-scene is only the cherry on top. Way to go, Criterion, for re-evaluating a movie that was utterly ahead of its time. If you watch the flick and still aren’t convinced, don’t miss the bonus commentary track and insightful essay from film critic David Sterritt.

Dead Ringer (Warner, $14.99 Blu-ray) is another one of those bonkers Bette Davis vehicles from the ’60s, this one directed with chilly precision by actor Paul Henreid. Davis plays dual roles as twin sisters Edie and Maggie, reunited after 20 years when Maggie’s husband – who was once Edie’s lover – mysteriously dies. Harboring vengeance and jealousy and about to lose her bar business, Edie kills Maggie, frames it as a suicide and proceeds to become Maggie, in a case of identity theft taken most literally. Edie thrusts herself into a foreign, gilded world of suspicious maids, butlers and chauffeurs, and we’re just waiting for her goose to be cooked. But the sordid plot tangle that ensues reveals Edie’s sociopathic murderess to be one of the film’s most moral characters, eventually deserving of our pity.

As with some of Davis’ other gonzo pictures, modern audiences may be inclined to snigger at her lack of inhibitions, not to mention the bombastic, invasive score by Andre Previn. And the sister-on-sister murder scene is unintentionally hysterical – somehow, we’re supposed to accept that Edie has changed into Maggie’s funereal black garments, none of which have a spot of blood on them! Still, nobody could communicate as much with their eyes as Davis does here and elsewhere; they dart around like nervous saucers, nearly bulging out of her sockets. Peter Lawford turns in a great supporting role as Maggie’s sleazebag Lothario.

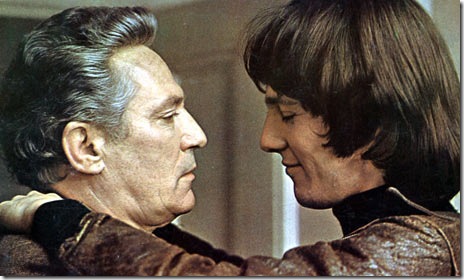

John Schlesinger directed the English anti-romance Sunday Bloody Sunday (Criterion, $34.99 Blu-ray, $24.99 DVD) in between Midnight Cowboy and The Day of the Locust. It’s remembered far less than either of these totems – and, admittedly, the pacing sags in the middle – but the film stings with almost as much alienation and cynicism. It was released in 1971, a sobering wake-up call after the freewheeling ’60s, capturing the bitter aftertaste of free-love euphoria. Murray Head plays Bob, a flighty installation artist stringing along two lovers simultaneously: Glenda Jackson’s unhappy office worker Alex and Peter Finch’s Daniel, an observant Jew and closeted homosexual. Both are aware that Alex gallivants with the other on the side, and both are foolishly OK with it.

Penelope Gilliatt’s smart and funny script follows this love triangle over about 10 days, ferreting out life’s ironies with inspired sarcasm. The film’s context could be ripped as much from today’s headlines in the States as much as England in the early ’70s; the country is on the brink of economic collapse, and Alex’s office is suffering layoffs. There are more pressing concerns than Bob, and viewers may want to shake his lovers until they realize this – while at the same time empathizing with them, because who hasn’t fallen in love with the wrong person? This is an underrated work from an underappreciated director.

A maestro of quiet, slow-burning Russian thrillers, Andrey Zvyagintsev’s latest release Elena (Zeitgeist, $24.99) should now enjoy the lengthy shelf life it never received in its limited theatrical release earlier this year. The 70-something title character, played by Nadezhda Markina, is retired and living in a grand apartment with her affluent husband of the past two years, Vladimir (Andrey Smirnov). The film’s conflict hinges on whether Vladimir will offer to pay for Elena’s ne’er-do-well grandson – who lives in a crummy shoebox with his white-trash parents – to enroll in college and thus avoid military service. When a sudden medical ailment threatens Vladimir’s future, the saintly, selfless Elena takes a disturbing action. With its slow, deliberate pacing and superb handling of interior space, Elena is intelligently directed – haunted by the specters of Rossellini and Ozu, with a dash of Hitchcock in its ability to inject suspense into otherwise benign montages. A wintry crime thriller that avoids all the trademarks of a traditional crime thriller, Elena’s full-circle ending is a bitter pill, its subtext resonating with hopeless tragedy.

Robert Wise’s Three Secrets (Olive, $27.85 Blu-ray, $19.99 DVD), from 1950, should probably be riveting: It centers on the expedition to rescue a 5-year-old orphaned boy in the mountains, the apparent lone survivor of a private plane crash that killed his adoptive mother and father. Instead, it’s structurally dull, settling on the lives of three women who could each potentially be the boy’s birth mother. Each fulfill hackneyed archetypes – Eleanor Parker’s housewife, Patricia Neal’s hard-nosed newspaperwoman and Ruth Roman’s damaged showgirl – and one by one, Wise and the movie’s two screenwriters insist on wandering off the exciting reservation of the boy’s rescue mission to unfurl the women’s emotional baggage. Because the present-day action is set five years after the end of the Second World War, the film has something to say about how wars tear relationships apart on the home front, but the message that comes across more clearly is that women obviously need men to survive. The women turn into puddles at the feet of callous males – even Neal’s world-weary, workaholic war correspondent grovels to her selfish beau. Feminist viewers take heed. Needless to say, this being a picture made under the Hays Code, the topic of abortion is never broached, and during their flashbacks, the women look about as pregnant as I do.