Criterion has waited until December to release what should go down as one of the most monumental home video releases of the year: Godfrey Reggio’s Qatsi Trilogy, packaged together in glorious Blu-ray for the first time ($53.99, same price for DVD). Three earth-shattering experimental features set to the music of Philip Glass, the Qatsi films are wordless symphonies of cities, countries, cyberspace and the universe at large, all of them completely different and yet hauntingly alike, cut from the same cloth of consternation and anxiety at the restless propulsion of modern life. Taking their difficult-to-pronounce names from the Hopi language, they are the rare movies that seem tailored to both IMAX cinemas, where spectacle is celebrated, and modern art museums, where pensive study is encouraged.

The trilogy begins with 1983’s Koyaanisqatsi, a picture unlike anything produced before it. In the beginning, Reggio’s camera glides across nature’s bounty – cliffs and mountains, fields of motley flowers, endless skies and roiling, wavelike clouds. Lines, color, geometry and symmetry seem to matter more than the mesmerizing vistas that are actually being filmed. Then, with the presence of the first agribusiness tractor, Glass’ hypnotic score takes a more dramatic turn, engendering a feeling of dread enjoined with wonder, as endless turbines, staggering skyscrapers, jumbo jets, military transportation and superhighways create the infrastructure of modernity. This in turn leads to inevitable destruction via wars, one of the threads connecting the three films.

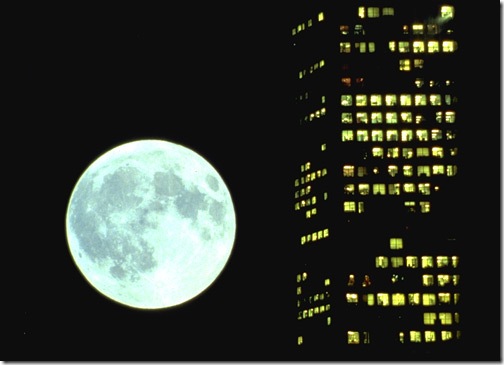

As a sea of identical high-rises dot an urban canvas of anonymity, population seems to reach critical mass. Using time-lapse photography to capture the world in a state of perpetual hyperspeed, Reggio’s hallucinogenic depiction of city life reduces everyone to lemmings in a rat race – tiny molecules under a microscope, whose cars zip along like tiny models controlled by an unseen child. Eventually the strips of nocturnal traffic whiz by with the speed of electrical circuits pulsating along strips of light, in cities that begin to resemble giant microprocessor chips. Finally lingering on the poor, dying and infirm, Reggio’s pessimism at the hazards of progress becomes abundantly clear, ending with a symbol that suggests a monumental failure of man’s ambition.

In Powaqqatsi, released five years later, time is slowed down rather than sped up. Subtitled “Life in Transformation,” the film visits locales from Peru to Pakistan to Israel and the Serra Pelada gold mines, observing Third World natives in their daily routines with a mixture of ethnography and poetry. For most of the time, Glass’ music is celebratory but with an undercurrent of encroaching dread, which rears itself, once again, in the form of progress’ inevitable intrusion.

Television images erode into each other in a gelatinous mass of distraction, and cars clog the roads and block images of the natives, as Reggio begins to experiment with canted angles and fish-eye lenses – a world slanting increasingly askew. The images eventually become spectral, as bodies and cars turn into translucent superimpositions, suggesting, I think, the possibility of reincarnation and the afterlife, where more peaceful lives can be rebuilt.

If Koyaanisqatsi is the most stirring film in the trilogy and Powaqqatsi is the most mysterious and mystical, its closing film, 2002’s Naqoyqatsi, is the most profound. Glass’s strings are weeping and mournful from the get-go, and the musical pace rarely picks up. The visual manipulation Reggio had been toying with in the first two films completely takes over in his survey of the universe in the new millennium. The natural has fully seceded to the virtual: X-rayed, sepia-toned and discolored images of humans share screen time with cosmic montages of binary code combinations, mathematical symbols and astronomical visions.

Abstract armies of soldiers traipse through abstract battlefields, and cloned sheep give way to athletes majestically defying the odds in sport after sport, their bodies either genetically modified or artificially enhanced, articulating the new paradigm of Bigger, Stronger, Faster. Simulated images of celebrities saunter across animated red carpets, and television remains an egalitarian arena to zone out, where images of Bin Laden and cheeseburgers share space with Martin Luther King and porn. Recreations of contemporary and historical cultural figures stare blankly into the camera, humanoid crash test dummies perish in accidents, and actors simulate virtual happiness in TV commercials. Real-life riots merge with images of first-person shooter videogames, blurring reality with fantasy.

Naqoyaqatsi is nothing less than an 89-minute study of trans-humanism as the major force transforming modern life, and the fact that the entire picture rushes by in a wordless, kaleidoscopic fantasia doesn’t make its conclusions any less scary. It’s a staggering end to a staggering trilogy.

For his follow-up to the critically acclaimed 2010 drama Dogtooth, Greek director Yorgos Lanthimos offers the oblique head-scratcher Alps (Kino, $24.99), about four basically gloomy denizens of hospitals and gyms – two nurses, a gymnast, and her coach – who offer to re-enact the lives of recently deceased people for loved ones willing to pay. Despite the way its promotional materials sell it, Alps is not about the mourning process so much as it is a meditation on the nature of acting, and how even in a ragtag “theater” troupe like this, the artifice of the job can threaten to overtake reality and fill emotional chasms. There is plenty of deadpan humor, disturbing behavior, sex and violence in Alps, which, if handled slightly more commercially, could have been a wickedly effective Todd Solondz picture. But everything is delivered with such de-dramatized art-house implacability, and with such a confounding absence of exposition, that moments that should resonate seem unmoored in a Pollock painting of a narrative. As a result, the film is only fitfully engaging, even approaching tedium from time to time.

Jennifer Baichwal’s documentary Manufactured Landscapes (Blu-ray debut, Zeitgeist, $29.99) opens with a tracking shot for the ages, one of those ambitious, never-ending tracks along an endless expanse that have been favored by the Jean-Luc Godards and Wes Andersons of the fiction world. This time, it’s a real factory, in China, that might just have its own zip code. By using an eight-minute, unbroken take to survey row after row of work tables, boxes, small machines and anonymous laborers, Baichwal stresses the enormity of globalization’s impact on the world, making us continue to watch long after we get the picture.

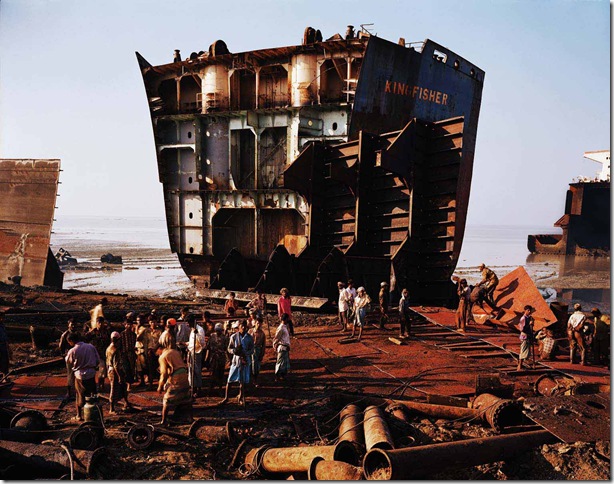

Videos like this one make for a perfect complement to the photographs of Canadian artist Edward Burtynsky, the subject of Manufactured Landscapes. Baichwal follows the award-winning photographer to far-flung locales around China and Bangladesh, where he snaps contradictorily beautiful images of industrial incursions on pristine nature – fields of toxic recyclables, overworked oil tankers and derricks, quarries and mines, and the construction of the Three Gorges Dam, the controversial Chinese economic booster that displaced more than a million of its country’s residents. The movie confronts the dire costs of Western convenience – and the sacrifices China has made to become an emerging world power – while never once preaching a position. Burtynsky and Baichwal both act as journalists chasing narratives, not zealots creating them, and this matter-of-fact approach makes Manufactured Landscapes an articulate and credible bit of reportage dressed up in the biography of an artist.

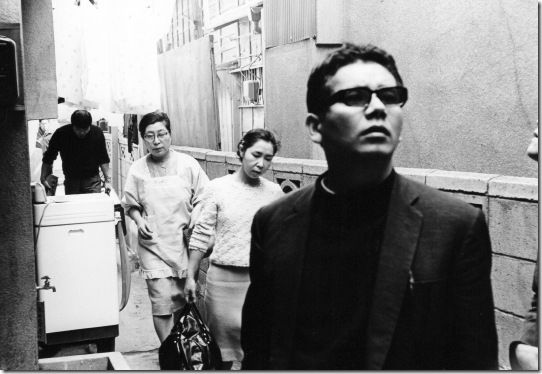

Japanese auteur Shohei Imamura is known for his dark and surreal crime dramas (The Pornographers, Vengeance is Mine), but he was also an innovative documentary filmmaker, as evidenced by an indispensable three-disc collection from Icarus Films ($40.48). The main attraction here is the extraordinary A Man Vanishes, from 1967, in which Imamura seeks to solve the real-life missing persons case of a handsome, 32-year-old businessman and alleged embezzler. Imamura scours cities and towns, interviewing friends, family and coworkers and retracing the vanished man’s footsteps, acting as detective, therapist and philosopher as much as filmmaker. The businessman’s fiancée tags along the entire time, eventually opening repressed familial wounds when she steers Imamura toward investigating her own sister, a middling geisha, for her beau’s disappearance.

There are visits to mediums, sordid soap opera scenarios and tawdry love triangles, filmed in a way that more often suggests surveillance than permission: Eyes are redacted with black boxes, visual obstructions occlude pivotal conversations, and audiovisual mismatches force us to piece together the drama just as Imamura does. If this was all A Man Vanishes was about, it would be a terrific example of cinema as investigative journalism, but Imamura has much more up his sleeve. Key revelations suggest that his documentary has been hijacked by fiction, or vice versa, with actors in fact portraying the subjects involved – long before “docudrama” became a buzzword. The film it most anticipates is Abbas Kiaorstami’s Close-Up, which I thought was 100 percent original until I saw this, a prescient docu-fiction hybrid that shows how the very presence of a camera alters reactions and changes perceptions – Imamura’s, his characters, their real-life counterparts and the audience’s. This wonderful set includes five other Imamura documentaries from the 1970s, ranging from 45 to 75 minutes each.

In Liberal Arts (IFC, $23.98 Blu-ray, $12.99 DVD), the second film from Happythankyoumoreplease writer-director-star Josh Radnor, the character he plays is suffering from a case of post-collegiate malaise that is only curable with the affections of a quirky, nubile sophomore. His Jessie Fisher is a bookish, 35-year-old college admissions adviser in New York City whose girlfriend has just left him. The opportunity to speak at the retirement ceremony of a much-loved professor (Richard Jenkins) at his Midwestern alma mater leads him to meet Zibby (Elizabeth Olsen), the intriguing daughter of a mutual friend. Thanks to Zibby’s maturity and precocity and Jessie’s stunted growth, the two click, despite a more than 15-year age difference that will eventually become a problem.

The movie makes some salient points about the denial, and ultimate acceptance, of aging, as well as some memorable debates about literature, from David Foster Wallace to Twilight. And the corrosive performance by Allison Janney as a hard-nosed professor is one of her best in years. But the rest of this picture is pretty indefensible, and difficult to take seriously. The clichés build like the bricks of a student union, starting with Zac Efron’s stoner character who speaks in profound aphorisms – an impossibly eccentric cartoon. Olsen deserves better roles than the Manic Pixie Dream Girl archetype she’s saddled with portraying. As a director, Radnor films the college campus with a halcyon glow, as a paradise of academia framed by verdant foliage and elegantly lit buildings. Even the romantic poets Jessie once studied in his favorite college course would probably want to barf at the sight of it.