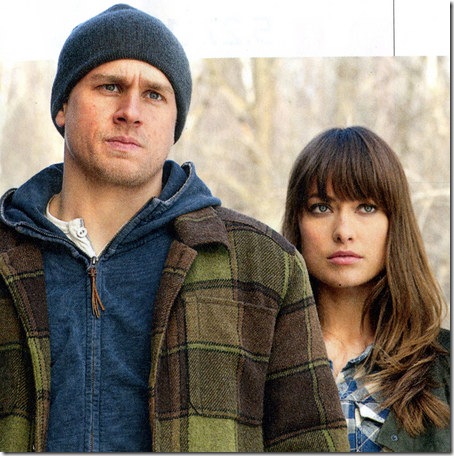

“This is kind of like an old movie, don’t you think?” Liza (Olivia Wilde), a runaway bandit in Stefan Ruzowitsky’s Deadfall ($24.99 Blu-ray, $13.28 DVD) asks Jay, a former pugilist newly released from prison who makes the mistake of picking her up as she shivers in a crepuscular blizzard. Thank the heavens for at least this brief semblance of ironic self-awareness in an otherwise stolid neo-noir that takes itself laughably seriously. Stranded in the snowy wilderness after their car careens off the road and their driver perishes with it, Liza and her brother Addison (Eric Bana) split up, hoping to evade the authorities and eventually steal away to Canada together. Deadfall divides its time between the siblings’ semi-incestuous relationship, Jay’s emotionally scarred boxer, and, most ludicrously, Hannah (Kate Mara), a pretty police officer denied the respect of her macho male colleagues and disapproving father/police chief (Treat Williams, reduced to uttering misogynist comments about his daughter’s tampon coming loose in the middle of a tense job). In fact, all of the major characters are connected by their unresolved daddy issues; the cartoonish, programmatic screenplay, by Zach Dean, is lacquered in unconvincing pop psychology and unearned sincerity. It’s partially redeemed by its on-location atmosphere, occasionally punchy dialogue and polished, if familiar, turns from Kris Kristofferson and Sissy Spacek, slummin’ it as Jay’s parents.

The disciplined and singularly impressive 1958 classic The Ballad of Narayama ($23.95 Blu-ray, $14.99 DVD) takes as its subject an old Japanese folk legend about the practice of abandoning elderly parents to die on the Narayama Mountain as they turn 70. The first two-thirds of this peculiar and mesmerizing film presents the casual lead-up to this barbaric journey, treating it as a joke or, in some cases, with the promise of anticipation. By the end, the actual trip up the mountain, with son Tatsuhei (Teiji Takahashi) carrying his mother Orin (Kinuyo Tanaka) on his back to perish in the snowy abyss, becomes as devastating to watch as it should be. Directed by the unsung genre-hopper Keisuke Kinoshita, The Ballad of Narayama is a meditation on the acceptance of death and aging, filmed as a sensorial feast told partly in dialogue and partly in sung narration, chanted over the rough-hewn string-plucking of a primitive instrument known as a samisen. The music is an austere counterpart to the gloriously verdant visuals, shot entirely, and obviously, on studio sets with greener greens and yellower yellows than any director would be likely to find in the real world. Bathing certain passages in bold red and green filters, Kinoshita creates a feverish trance-film whose themes couldn’t be more sobering. Unusually for Criterion, this edition is absent supplements, save for a nice essay from critic Philip Kemp.

Released in 2000, Christopher Guest’s Best in Show (Warner, Blu-ray, $14.99), only feels more prescient with every passing year. Following five fictional parties before, during and after their appearance at Westminster-style kennel club show, Best in Show satirized competition documentaries years before films like Spellbound, Murderball and Wordplay established the formula. The various handlers – a Botoxed gold-digger with a poodle, two gay man with a shih tzu, a fly-fishing redneck with a bloodhound, etc. – offer a hilarious cross-section of America. And moreover, the film presents an astute send-up of the ways in which humans anthropomorphize their dogs, and this commentary can be as uncomfortable as it is hysterical (Of the losing animals, the event organizer laments, “There will be sad eyes on some of the dogs who have come a long way to be here”). Needless to say, the cast of Guest regulars, particularly Fred Willard, Eugene Levy and Jane Lynch, is dynamite.

Yet another twist on the 18th-century novel-turned-play-turned-film, Dangerous Liaisons (Well Go USA, $17.39 Blu-ray, $12.78 DVD) transfers the ludic narrative of lust and love to 1930s Shanghai. A glitzy, sun-dappled noir, the film plays out with trendy Great Gatsby nostalgia, as Mo and Xie (Cecilia Cheung and Jang Dong-kun), a affluent socialite and playboy who share a romantic past, agree to play with the heart of a sensible humanitarian named Du (Ziyi Zhang); if Xie can successfully bed her and leave her, then he can once again have Mo. The skeleton of a quality story and the faint echo of Stephen Frears’ excellent 1988 translation of the same source material are the only salvation of this poorly written (“Crossing Jin Xiuehah is a dangerous game!” one character actually proclaims, a line Bogart would have troubled reading with a straight face) and clumsily directed thriller. The director, Hur Jin-ho, channels the insecure impatience of a Rob Marshall, cutting like a barber when lengthier shots would create a more memorable atmosphere. Sometimes his edits are downright whiplash-inducing, and when he’s not cutting, he’s zooming; his overall aesthetic is that of a child with severe ADHD. Furthermore, every action is telegraphed by manipulative musical cues, and the characters’ broad stereotypes transcend the subtitles. Even the movie’s sensuality is presented as a polite, almost chaste sort of eroticism, guaranteed to offend no one.

The spirit of Andrei Tarkovsky casts a poetic pall over the challenging Russian drama Silent Souls ($24.99 DVD), an art-house riff on the road-movie genre whose perpetually overcast settings suggest the industrial bleakness on the outskirts of The Zone in Stalker. If none of what you just read makes any sense, then you’re probably not ready for this feature, a weighty and languorous 75-minute ramble on mortality, memory and a vanishing culture – that of the Meryan people, a group of modern Russians trying to maintain the rites and customs of their indigenous ancestors. Two such Meryans – an aspiring writer who works in a paper mill and his supervisor – travel from their remote town of Neya into another remote city to bury the supervisor’s wife in the tradition of their people, which means incinerating the body and depositing the ashes in a river. The journey traverses landscapes of personal history as much as geography, as the current burial triggers reminiscences of the narrator’s own history with death. Again, as with Tarkovsky, director Aleksey Fedorchenko’s images burn themselves into your retinas; for audiences tuned into its strange and sometimes mystical vibrations, this is a film to be watched, re-watched, analyzed and, above all, celebrated.