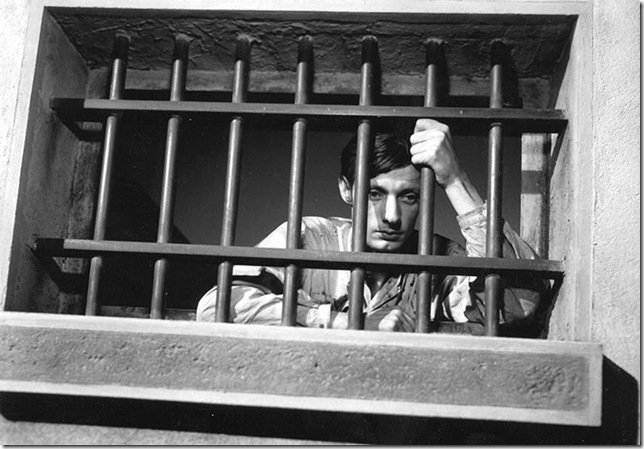

The straightforward matter-of-factness is right there in the title: A Man Escaped (Criterion, $31.86 Blu-ray, $23.99 DVD). It’s in the past tense, so you know before starting Robert Bresson’s 1956 prison-break masterpiece – based on the memoirs of Andre Devigny, a French POW during World War II – that the protagonist will succeed. For Bresson, suspense has no appeal; it’s all about the formal process of the escape, in which the director dispassionately revels for 100 minutes. François Leterrier, a hollow-cheeked, handsome cipher, plays Fontaine, our conduit into the claustrophobic regimens of Nazi penitentiaries. Arrested for his involvement in a bridge demolition, Fontaine jumps out of a police car in the opening scene, his first, and unsuccessful, attempt to his escape his fate. He’s brutalized for his actions, and for the rest of the film, clad in a shirt stained with his own blood, he plans his impossible breakout. Aided by fellow inmates who whisper their encouragements and assist him with planning and materials, he becomes something of a proto-MacGyver, discreetly repurposing any and all objects from his Spartan cell into primitive chisels, hooks and ropes, stopping in a panic at every errant cough. A series of complications, from a promised search-and-seizure to the arrival of cellmate, impede his progress.

There is no musical score, save for the occasional brilliant, incongruent employment of Mozart’s Mass in C minor. Otherwise, the soundtrack is composed of natural sounds – handcuffs shackling and unshackling, makeshift tools scraping away at concrete walls and doors, feet shuffling on the courtyard ground, trains rumbling past the prison. Bresson creates a miniature city symphony of unadorned noises, which goes a long way toward creating a tactile sense of place, enhancing a world that operates on its repetitive rhythms, textures, patterns and rituals – a blueprint for structure and predictability punctured by Fontaine’s interruptions.

As always with Bresson, we’re just as struck by what is not shown as by what is, and even his omissions are masterly. A Man Escaped is a miraculous reminder of the purity of cinema, of the medium’s potential for personal, sensorial enrichment when commerce is removed from the equation. With respect to The Great Escape, Jacques Becker’s The Hole and Jim Jarmusch’s Down by Law, this is, for my money, the best prison-break film ever made. The Criterion edition is well worth purchasing, with a trove of valuable extras including Bresson’s first on-camera interview (for French television in 1965), a 1984 documentary about Bresson featuring interviews with world-cinema luminaries, and The Essence of Forms, a 2010 documentary about the director’s work.

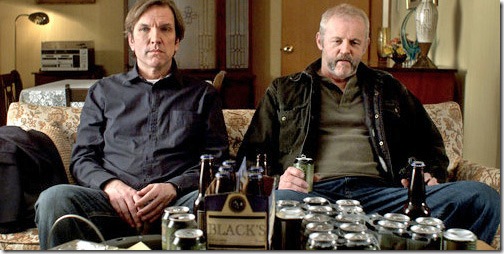

Who knew Martin Donovan could direct? The Hal Hartley protégé and gifted character actor’s debut feature, Collaborator ($14.99), is both disturbing and comic, shot through with an eerie and weary intelligence and boasting a title that functions on multiple levels. He cast himself as the lead, Robert Longfellow, a Broadway playwright on a downward career spiral who all but abandons his wife and children to creatively convalesce in his mother’s suburban home in Los Angeles. He visits an old flame (Olivia Williams, of Rushmore fame), sees a producer about a job, talks to his mom about sending her to a nursing home and, most significantly, engages his ex-con neighbor Gus (David Morse), an acquaintance from grade school. Gus’ seemingly benign request to have a beer and catch up with Robert turns the film on its head, metamorphosing from a slow-moving navel-gazer to a tense psychological power keg that will put both of the characters’ lives in danger.

There is a delectable chemistry between Morse’s bruising jingoistic simplicity and Donovan’s squinty, left-wing intellect, and the more time their characters spend, the more they reveal themselves to be two sides of the same unstable coin. Donovan’s best decision as writer, director and actor is to cast his own protagonist as a man who is far from a saint accosted by a maniac – rather, Robert is lying and neglectful toward everyone he cares about, drifting from project to project with his sights only on the next positive review. No matter how the movie’s intense set piece concludes, the characters’ damages have already been diagnosed and inventoried under Donovan’s observant eye.

Arriving in a ravishing Blu-ray transfer from Cohen Media Group, the superlative new edition of Luis Buñuel’s Tristana ($19.99 Blu-ray, $14.99 DVD) captures all of the subtlety and nuance in a quietly disturbing study of shifting class and gender power dynamics in late 1920s Spain. I’d seen the film about a decade ago on scratchy VHS, where I couldn’t appreciate a gorgeous image toward the beginning of the film that crystallizes the director’s intentions. It’s a deep-focus shot of Tristana (Catherine Deneuve), an innocent young ward living under Don Lope, Fernando Rey’s bloviating aristocrat. She’s having a snack of fried bread in the foreground, while in the background, two deaf-mute children from a local school toy with a bird trapped in a cage. Tristana may have the illusion of freedom, but under the don’s lecherous grip, she becomes that bird, trapped and pale in his outmoded manse while he treats her as both daughter and lover, breaking his own rule to never seduce “strange flowers born of perfect innocence.” Initially, we support Tristana’s covert trysts with Franco Nero’s starving artist, and her defiance of her pompous guardian. But this is a Buñuel film, so expectations are expectedly shattered, replaced by shadows, nightmares and reversals. What begins as a quest for Tristana’s self-actualization becomes something else in its surprising second half, turning a Postman Always Rings Twice-style narrative of a kept woman’s revenge on its head, and making us care for Don Lope in the process. Tristana was one of the savage fantasist Buñuel’s most realistically grounded films, though its one recurring surrealist set piece is an unforgettable knockout, the only image I retained in my memory from that pitiful VHS viewing all those years ago.

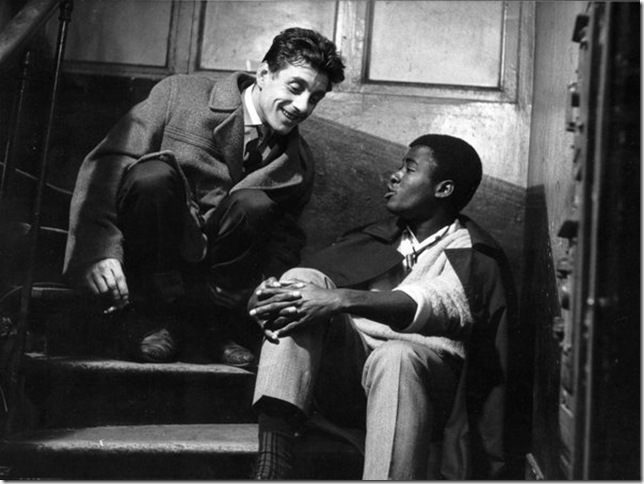

Could it be that Criterion’s recent release of Chronicle of a Summer ($34.99 Blu-ray, $24.99 DVD) is the first Jean Rouch feature film ever released on DVD in the United States? Apparently so, which is hard to fathom considering the wide shadow Rouch has cast on the French New Wave, the documentary genre and the very idea of a hybridized docufiction. An anthropologist whose medium of exploration was a movie camera, Rouch directed more than 20 movies in a nearly 60-year career, and unless you’ve been hoarding old Rouch VHS tapes or have seen some of his films in other-region DVDs, Chronicle of a Summer will likely be your introduction to his style — talky but poetic, always searching for truth in a medium overtaken by artifice.

Co-directed by sociologist Edgar Morin, Chronicle begins with Rouch and Morin themselves discussing their film, which is predicated on a single question to be posed to ordinary Parisians: Are you happy? This idea soon gives way to the stories of a number of real-life individuals the filmmakers meet, whose thoughts and emotions will fill the next 90 minutes: a factory worker, an African émigré, a struggling student, a depressed young woman from Italy, a Holocaust survivor. Reflections on work, race, war and genocide loom large over the conversations, filmed in 1960 at the twilight of the industrial age. They seem to forecast the protests of May 1968 and could apply just as easily to labor relations in the United States today, with workers living beyond their means and struggling to find contentment in workaday drudgery.

For Rouch and Morin, form is at least as important as content, if not more so; they regularly insert themselves into the “story,” interviewing their subjects and inciting new topics as a test for how authentically their cast can act when a camera is always photographing them in claustrophobic close-ups. Opinions on this will vary, but one thing is for sure: Chronicle of a Summer is a perfect example of how films can morph into something else by the sheer process of making them. It’s so alive to the possibilities of documentary cinema that it’s never boring, even when its subjects meander. Let’s hope it’s the first sign of more Rouch titles to come down the pike.

I know what you’re thinking: Not another black-and-white, animated period noir from the Czech Republic. Kidding aside, Tomas Lunak’s Alois Nebel (Zeitgeist, $24.99) is a true original — a tone poem shrouded in shadows and fog. Its country’s Academy Award entry for Best Foreign Language Film in 2012, Alois Nebel is set during the twilight of the Cold War. It charts a tumultuous period for the antisocial train dispatcher of the title, whose quiet life of memorized timetables is uprooted when a Slovakian fugitive takes refuge in his station, carrying a photograph that triggers disturbing memories from the Nazi occupation of his youth. The film sounds dreary, and sometimes it is – but it also harbors a surprisingly droll wit. It’s based on a popular comic book trilogy, and it does indeed resemble a graphic novel sprung to life, with each cut signaling a shift to the next panel. The rotoscope animation, familiar to viewers of Waltz With Bashir, Waking Life and Schwab TV ads, creates a sense of unparalleled realism to the action, ensuring that the opaque narrative is presented with a vivid clarity of detail. One can imagine the movie shot as a live-action drama, but it wouldn’t be nearly as compelling. Like the trains it so often depicts, Alois Nebel lumbers slowly by Hollywood standards, but it’s well worth a ride.