Warner Home Video has waited near Father’s Day to market and release two exceptional new Blu-ray collections of gangster cinema, old and (comparatively) new. If these are the kind of gifts the studio has prepared for dads, I’d happily take a Father’s Day every month.

The Ultimate Gangsters Collection: Classics ($44.98) features four titles from the ’30s and ’40s, when Warners all but invented the gangster genre: Little Caesar, The Public Enemy, The Petrified Forest and White Heat, along with a feature-length documentary about the gangster films of the period. Ultimate Gangsters Collection: Contemporary ($46.95) is more auteurist in nature, packaging five flicks from three prominent directors: Michael Mann’s Heat, Brian de Palma’s The Untouchables, and three from Martin Scorsese (Mean Streets, GoodFellas and The Departed). In the interest of time and word count, I’ll be limiting the rest of this review to the latter trio of hefty masterpieces, which alone are worth the box set’s purchase.

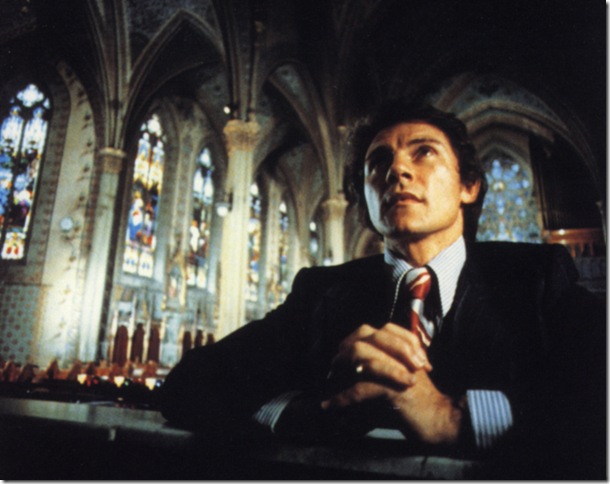

Of the great Scorsese gangster triumvirate, 1973’s Mean Streets makes for the most exciting and crucial addition to the Blu-ray canon; in this entire box set, it’s the film that is shown the least on television, and more than any film before it, it helped established the director’s signature themes of cosmic fatalism and lapsed faith in the harsh worlds of wayward men. Harvey Keitel is a small-time hood scraping by in Little Italy, courting Amy Robinson’s epileptic sweetheart while trying to reconcile a life of petty crime with his belief in the prayers of Saint Francis. He carries the burden of his erratic friend Johnny (Robert De Niro, in his breakthrough performance), a desperate hustler in debt to the entire New York underworld, whose actions are destined to shatter Keitel’s dreams.

Forty years after Scorsese shot the film on a relative shoestring of half a million dollars, it’s as fresh as a Georgia farmer’s newly grown peaches. Scorsese’s camera lurches, gambols and hurtles full-throttle into the characters’ grimy milieus and discomforting psyches, creating an environment of perpetual volatility where anything can happen, and it often does. The movie’s instability makes it feel stylishly twitchy and very much alive, reflecting the spontaneity of Cassavetes, the New Wave sensibilities of Godard, and the fractured violence of John Boorman, whose Point Blank is directly referenced in its climax.

Within Keitel’s intense powder keg of a performance lies epic themes: the futility of a hood trying to go straight, the unattainable dream of a normal life, the impotency of his religious faith. It’s an extraordinary document of its time and its director’s flash of nascent genius, to say nothing of its status as a touchstone film in the relationship between sound and image; the movie’s soundtrack of jubilant ’60s pop hits and Spanish-language love songs is a masterpiece of counterpoint.

If Mean Streets is arguably Scorsese’s grubbiest movie, then GoodFellas is his poppiest. Still probably the most widely seen title in the director’s oeuvre, it’s become, like Scarface and Pulp Fiction, a rite of passage in college dorm-room parties and local film societies, if those exist anymore. Watching it for the third time, GoodFellas now feels like a vintage Greatest Hits concert, a procession of indelibly quotable moments: the body kicking around the trunk, that awesome point-of-view tracking shot in the mob bar, Joe Pesci’s “What’s funny about me?” rant, the borrowing of the meat cleaver, the surreal wedding scene, Pesci’s psychopathic slaying of poor Michael Imperioli at the poker table, Ray Liotta’s very bad day complete with a helicopter tail and $60,000 worth of flushed cocaine.

Believe it or not, I never really loved this utterly absorbing, episodic true-crime tale until now, seeing it in this glorious Blu-ray transfer. In Henry Hill’s impossible attempt to combine his career in organized crime with a normal, domesticated life, GoodFellas anticipated The Sopranos by nearly a decade, the action choreographed with humor and matter-of-fact intensity from maestro Scorsese.

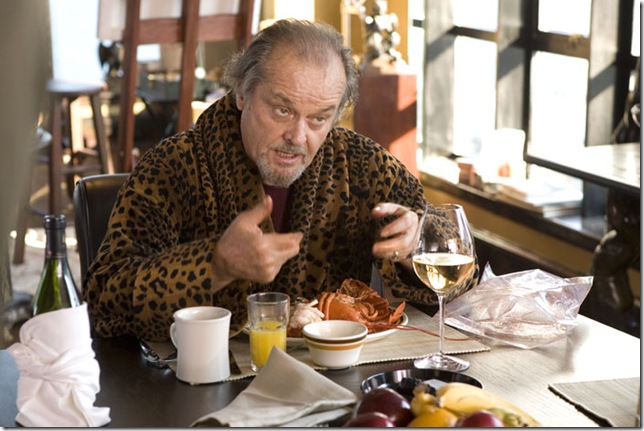

For The Departed, Scorsese abandoned his stomping ground of Italian-Americans in New York for Irish cops in Boston, but it’s a similarly searing commentary on the moral calculus of unhinged men in violent professions. Only this time, Scorsese and screenwriter William Monahan based their film on the Hong Kong thriller Infernal Affairs, so the action tends to follow the pulpy, splatter-ful formula of Asian pistol operas more than the sobering black-and-whiteness of American crime cinema.

Here, nothing is sober: Everything moves in peaks and valleys of intoxicating rhythms until everybody dies, like a Shakespearean tragedy executed by John Woo. Jack Nicholson’s gonzo, unforgettably Luciferian performance as the film’s crime lord is only the movie’s most up-front id; the rest of it is similarly over-the-top and nihilistic, and it’s all the better for it. There’s nothing quite like watching the sinister vibrations emanating from dead men’s cellphones when it comes to gauging our 21st century connectedness, Scorsese-style.

The pair of ’50s Westerns Jubal ($14.99 DVD, $21.83 Blu-ray) and 3:10 to Yuma ($21.83 DVD, $29.83 Blu-ray) represent the Criterion Collection’s first foray into the cinema of the prolific and versatile Delmer Daves. And they reveal the work of a superb craftsman, if not an underrated artist, toiling in commercial genres.

Jubal seems to borrow from the Anthony Mann playbook of repurposing noirish fatalism into the Technicolor vastness of the west: It’s basically The Postman Always Rings Twice with horses and six-shooters. Glenn Ford’s bedraggled outsider Jubal Troop, his tragic past long behind him, comes into town — or, rather, rolls into town, down a rocky hill, exhausted and near death — and is taken under the employ of Shep, Ernest Borgnine’s kind-hearted but dense rancher. Jubal is good with a steer and a rope and, for Borgnine’s well-figured wife Mae (Valerie French), he’s an awfully handsome change of pace.

They take a shine to each other, speaking dialogue that brims with sexual subtext, as Jubal clutches a hot poker meant to represent something else. “I suppose you needed some wood,” says Rod Steiger’s Pinky, one of Shep’s volatile and jealous employees, when he sees Jubal reciprocating her flirtations in the barn. It isn’t long before Mae suggests to Jubal, in so many words, that it sure would be nice if Shep were out of the picture.

The pieces are in place for a sinister psychosexual quadrangle where hardly anyone is altogether decent. More so than its noirish patina, this is the modern, hot-boiled stuff of Douglas Sirk. Ford and French really smolder, and Jubal’s most authentic moments find the two non-lovers practically penetrating each other with unspoken glances. The movie’s climax is boilerplate, but it’s a fascinating Freduian roller coaster getting there.

A year later, Glenn Ford reunited with Daves for 3:10 to Yuma, only this time he’s the villain – the leader of an outlaw gang who is captured by an embattered police force. Van Heflin’s Dan Evans, a meek farmer with a quick draw, is suffering through a financially crippling drought, prompting him to accept a $200 suicide mission to transfer Ford’s Ben Wade to a hotel in the perfectly named Contention City, where he and a small contingent plan to outmaneuver Wade’s team of loyalists. From there, they’ll send him on the 3:10 train to Yuma, where the hoosegow awaits.

Based on an Elmore Leonard story and successfully remade in the Aughts by James Mangold, 3:10 to Yuma is a genre classic for plenty of good reasons – it’s thrilling, suspenseful, smart and thoughtful, with its protracted scenes of Evans and Wade alone in the hotel room functioning as a psychological study of morality’s strength in the face of temptation. And the offers of financial security from Wade if Evans releases him are awfully tempting when proposed by Ford, who wrote the book on charming, charismatic bad guys; no doubt audiences related more to Ford’s cool, dashing outlaw than Heflin’s lanky hayseed.

Part of Daves’ genius, in his noirs as well as his Westerns, was in subverting our expectations and questioning our own affiliations and moral compasses. It doesn’t hurt that the storytelling is flawless, the photography gorgeous, and the violence bracing in what it doesn’t show: the shadow of a man hung by the neck from a chandelier has more potency than any amount of gore.

The Last Stand (Lionsgate, $24.96 Blu-ray, $19.99 DVD) is not a good movie by the stretch of anybody’s imagination, but it’s certainly a fun one – directed with blood-soaked, Grand Guignol flamboyance by South Korean auteur Jee-woon Kim (The Good, The Bad, The Weird). Arnold Schwarzenegger, in his first post-gubernatorial starring role, plays the blocky, impenetrable sheriff of a small U.S. border town, forced to corral a ragtag band of greenhorn patrolmen, dubious weapons salesmen and even convicts to defend his land against a jail-broken druglord (Eduardo Noriega) speeding across the Mexican border in a refurbished sports car that drives “faster than any chopper.”

With its litany of head-slapping inevitabilities and shameful one-liners, Andrew Knauer’s script is either embarrassingly bad or hiply self-aware; at the beginning of the film, Arnold, enjoying a day off in civilian clothes and dorky boat shoes, actually says “This should be a quiet weekend” with a straight face. Then again, Schwarzenegger is incapable of understanding irony, which makes him the perfect foil to translate Jee-woon’s poker-faced action satire. He’s also a remarkably bad actor, reading his lines as if from a teleprompter, which tends to make the competent supporting cast around him, like Luis Guzman and Johnny Knoxville, look like Brandos.

Try not to think too much, and you’ll easily get sucked in by the director’s inventive, ultra-violent set pieces and creative car chases, like the climactic race through endless fields of corn, with stalks of Monsanto’s bounty thumping across the characters’ windshields like genetically modified hail. And yet, beneath all the explosions, dismembered body parts, phallic firearms and degenerate silliness, I swear there’s at least a kernel of Rio Bravo romanticism in there somewhere.