The title of Satyajit Ray’s outstanding 1963 drama The Big City (Criterion, $34.99 Blu-ray, $23.48 DVD) is almost a misnomer. It contains few shots of metropolitan expanse but, rather, is comprised almost entirely of close-ups and medium shots of a single family in everyday peril — which in turn could be a microcosm for any number of families, in India or anywhere else, in the early 1960s or today. The film’s strikingly modern depictions of banking crises, workplace politics and subtle sexism could just as easily fuel a plot in present day, highlighting both the film’s prescience and the reality that the more things change, the more the stay the same.

Change, nonetheless, is the key theme underlying everything in The Big City, which captures India’s progression from a traditionalist economy of single-job households to the new paradigm of working mothers. The film is set in a cramped apartment in Kolkata, where Arati (Madhabi Mukherjee) lives with her banker husband Subrata (Anil Chatterjee), his mother and father, her sister, and their young son. That’s a lot of mouths to feed under one man’s salary, and rumor has it there’s going to be a run on Subrata’s bank. So Arati applies for, and soon accepts, a job as a door-to-door salesgirl for a knitting company, much to the shame of Subrata’s conservative father.

But Arati enjoys her job. It isn’t long before she’s making friends with Anglos, wearing lipstick and sunglasses, and making demands of her boss, all while Subrata’s career slides ever more quickly down the tubes. It isn’t long before Arati’s emasculated and bitter husband is bumming around the house, dispatched to menial tasks by its new breadwinner.

The Big City’s remarkable feminism can’t be overstated — compare its elliptical reversal of gender roles to the daffy Doris Day pictures that passed for women’s lib movies in the United States at the time. In Mukherjee’s performance, we see Arati graduate from timid housewife to self-actualized woman in the course of the film’s fast-moving 135 minutes, and it’s an incredible transition to witness.

But Satyajit Ray’s gift is that he’s an all-around humanist; he feels everyone’s pain. He also has deep reservoirs of sympathy for Subrata, even through his irrational bouts of jealousy and envy, because it can be shattering to swallow your pride for the good of the family. It’s heartbreaking to watch Ray frame him as a slugabed or interloper, clandestinely eavesdropping on his wife in a café as she meets with a client, coming to the realization that this person he’s come to love has evolved into a very different creature. At one point, during a particularly irrational rant, Subrata is framed in a tight shot clutching the window grates in his apartment — trapped, as it were, in a prison of modernity.

This sort of depth of feeling and understanding of family dynamics is a rare thing in world cinema, a spectrum running from Yasujiro Ozu to Mike Leigh and Hirokazu Kore-eda. And Ray belongs firmly in that masterful tradition.

Criterion’s release is a must-own, including new interviews with Mukherjee and a Ray scholar, along with The Coward, a Ray short film from the same period.

Just a couple of years after the end of World War II, the underrated French director René Clément released The Damned (Cohen Media Group, $26.93 Blu-ray, $19.99 DVD), an engrossing mix of war film and noir set on a submarine. A handful of high-level Nazis and an international cadre of their sympathizers board a U-boat on April 19, 1945, fleeing like cockroaches as Hitler’s retreat continues.

Leaving Oslo for a supposed safe haven in South America, their voyage is stunted by an onboard injury, prompting them to port in Royan, where they kidnap a country doctor — unknown to them, a German-speaking Jew who has just returned home from a lengthy evacuation.

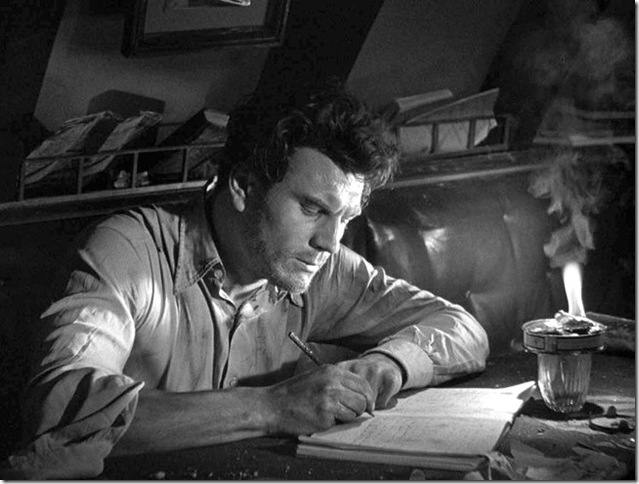

This is where Clément’s initially slow drama really gains traction, and it never lets up. Lit by burning lanterns and chiaroscuro flourishes, The Damned has many of the hallmarks of suspenseful pulp, including the requisite callous — and blonde — femme fatale, and, like many a noir, it chronicles the perils of a trapped man.

But it’s the film’s setting, and Clément’s attention to detail in his production design of the submersible, that sets this picture apart from any of its shadowy peers. Clément captures the submarine in all its crevices, crannies, and cramped compartments, including an impressive tracking shot following the doctor across several rooms of the claustrophobic boat — an oblong tube of snakes, scoundrels and their unwitting accomplices that he calls “a floating concentration camp.”

Death is both obscured and unforgettable in The Damned; one of the most chilling shots lingers on a curtain as it is slowly pulled off its rod, ring by ring, after the poor sap clutching it is stabbed off-camera. The more the submarine swims toward oblivion, the more the bodies pile up, as the ship’s inhabitants literally start to jump the sinking ship of Nazism.

It’s hard to justify the film’s unconvincing, tacked-on ending, as silly in its artifice as the denouement to Fritz Lang’s The Woman in the Window. But the rest is an idiosyncratic and poetic portrait of a vile political movement’s final days, as it flounders, shipwrecked, in history’s vast ocean.

Don’t miss this disc’s supplemental documentary, René Clément or the Cinema of Sketches, which tries to understand the director’s lack of canonization in the film-history pantheon. It offers valuable insights into this film and many others.

Chronicling a British noble family’s trials and tribulations from the Boer War in 1900 through the First World War and beyond, Frank Lloyd’s overstuffed adaptation of Noel Coward’s Cavalcade (Fox, Blu-ray and DVD combo pack, $23.48) was quite the event when it hit theaters in 1933. Heavy on history and pageantry, with set pieces that rivaled DeMille in their number of extras, Cavalcade was a giant-screen spectacle that successfully hoodwinked Oscar votes into granting it three statues, including Best Picture and Best Director.

Today, while the crane shots remain impressive for ’33, it’s hard to ignore the shallow and cardboard performances, still hopelessly rooted in silent-film gesticulations. The plot is a forced procession of early 20th-century global signposts, from Queen Victoria’s death to the sinking of the Titanic to the rise of Communism and the decline of organized religion, some of which are given ludicrously short shrift.

Still, stick around for the director’s montage of World War I battlefield action, a sequence that is both artful and budget-conscious: We don’t see any elaborate, war scenes but rather an epileptic frenzy of superimpositions, in which patriotic marches yield to mortal wounds and piles of corpses, as bombs pierce the soundtrack. It’s a moment of harrowing pure cinema in an otherwise safe and tasteful Picture of Quality.