The We and the I: The We and the I (Virgil Films, $16.22) is another masterpiece from Michel Gondry, and it’s a film that goes a long way toward rendering irrelevant the distinction between fiction and documentary. Mostly putting his fevered visual imagination on the back burner, Gondry takes a vérité approach in this study of Bronx high schoolers on a real-time bus ride following the last day of school. The “actors” hardly are that – they are real inner-city students, who answer to their own real names, and Gondry workshopped their characters over a three-year period. They act so naturally on camera that the artifice of performing is nonexistent.

The two main characters, around whom most everybody else orbits, are Michael (Michael Brodie), a private sentimental putting up a brash front with his cadre of bus bullies; and Teresa (Teresa Lynn), a sexually confused, clinically depressed girl who missed the last month of school for reasons that reveal themselves over the course of the film. The cast includes about two dozen others muscling for attention, and Gondry masterfully juggles countless stories that intermingle on these 18 dramatic wheels.

The bus is like Lord of the Flies – a modern Darwinian nightmare in which the more dominant animals prey on the weaker species. It’s an accurate vision of high-school youth in that nearly every bus denizen is obsessed with status, sex or both. They are self-delusional ciphers whose only sacred values are their egos and iPhones.

Gondry’s genius is that we care about them, deeply and unreservedly, by the end. The movie follows a three-act structure toward redemption and revelation. As the minutes go by, the characters gradually evolve dimensions; as the dialogue escalates, the chaos breeds koans. The film becomes a sensitive dissection of the insecurities it criticized early on, and nobody gets off easy, eventually finding truth and togetherness through tragedy. In other words, the “I” becomes “we.” I don’t know how Gondry did it; it’s just another example of his peculiar magic.

The Fly: Far from David Cronenberg’s haunting, masterly 1983 version of The Fly, Kurt Neumann’s 1958 CinemaScope version of the horror parable (Fox, Blu-ray, $21.28) suffers as many drawbacks as pleasures. This version remains a cautionary tale about the limits of science, with Al Hedison as the ambitious scientist who invents teleportation – he calls it a “Disintegrator Integrator,” which sounds like something from Schoolhouse Rock – only to transport himself with a fly and cross their DNA. This leads to harrowing results for the scientist, his wife Helene (Patricia Owens) and his brother Francois (an unusually blameless Vincent Price).

The film’s weaknesses are more or less endemic of the period: a child actor with a performance more wooden than a stilt factory; a clunky, nearly film-length flashback structure; and a screenplay riddled with sexist clichés. Hedison is the workaholic scientist with ideals, vision and a dense vocabulary, while Owens plays the unbothered housewife with limited mental capacity for scientific matters. Most of her scenes in the lab require her to furrow her eyebrows and cock her head to the side like a curious pug.

The film’s special effects are laughable 50 years on, but what doesn’t chill on a sci-fi or horror level still is effective as a heartbreaking story of a marriage and lives torn apart by a freak accident. Hedison’s decline into hybridization is emotionally painful to take in, much like Jeff Goldblum’s in Cronenberg’s vision, and it will stick with you for quite a while. And this version has one thing over the more modern take: It contains the most gripping and suspenseful fly-catching scene ever caught on film.

Autumn Sonata: Say what you want about the stilted nature of the countless soliloquies in Ingmar Bergman’s Autumn Sonata (Criterion reissue, $32.76 Blu-ray, $24.99 DVD), whose protracted mother-daughter row is rendered in solo theatrical riffs running for page after page. What it lacks in the natural banter of realistic dialogue it more than makes up for in its bravura performances and heart-wrenching dramatic sweep. The film remains an unforgettable chamber drama of abuse, neglect, memory and the prolonged pain of repressed anger.

Bergman, in her only performance for her directorial namesake, plays Charlotte, a concert pianist visiting her daughter Eva (Liv Ullman) for the first time in seven years. At Eva and husband Viktor’s (Halvar Bjork) bucolic parsonage, the mother and daughter will spend a day, night and painful morning stirring up decades of emotional cobwebs, mostly fixated on mom’s frequent absences, narcissism and workaholism while raising Eva.

In leveling her belated criticisms, Ullman’s character adopts the callousness of a sadist, and it’s hard to watch, even if it appears her assaults are justified. The women clearly are on two sides of the same coin, and they begin to resemble the melding figures in Bergman’s Persona; at one point, one of them says, “It’s as if the umbilical cord had never been cut.”

The characters’ brief memory flashbacks are filmed from a static and frustrating distance – cold, immobile and ungraspable, like partially completed paintings. But everywhere else, the director films his story as an opera of faces – grievances aired in extreme close-up – and Bergman, in particular, is astonishing at allowing her character’s entire history to flit across her countenance, continuing to find new avenues into her psyche.

Two Men in Manhattan: Thanks to Cohen Media Group, we finally have Region 1 access to Jean-Pierre Melville’s Two Men in Manhattan ($31.99 Blu-ray, $19.99 DVD). Released in 1959, this neat, jazzy curio helped bridge French cinema’s gap from classically structured studio movies to the freewheeling abandon of the New Wave. It seems to have its hands in both pies.

Melville plays Moreau, a hangdog French journalist in New York who is dispatched to track down a French delegate conspicuously absent from a U.N. assembly. He enlists the help of his dubious informant, Delmas (Pierre Grasset), a paparazzo who happens to possess snapshots of the missing diplomat with no less than three mistresses. Moreau and Delmas represent two fringes of reportage: the nationalist “mainstream” figure inclined to sweep unfavorable news under the rug, and the guttersnipe who will exploit any situation to his economic advantage, especially if the figure is a national hero. The more these two men in Manhattan scour the boroughs for the U.N. representative, the more their policies and demeanors clash in fascinating ways.

But more so than for its commentary on press freedoms, Melville’s offbeat, cloistered road movie is most memorable for its street photography. Though the interiors were shot in French studios, he filmed the exteriors in familiar New York locales rendered exotic under his lens. To the wail of perfectly moody jazz music, the opening image follows a car through the streets of a decidedly pre-Giuliani Manhattan – a glittering island of neon and sin – and the protagonists’ journey eventually takes them from Rockefeller Center to a Greenwich Village apartment, the Mercury Theater, a recording session at the Capitol studios, a strange Chinese bordello, a burlesque show in Brooklyn and the bright lights of Broadway.

There’s something slightly off in this Frenchman’s stylized take on New York that makes it unique among the many cinematic tributes to the city, from Bye Bye Braverman to Taxi Driver and, of course, Manhattan.

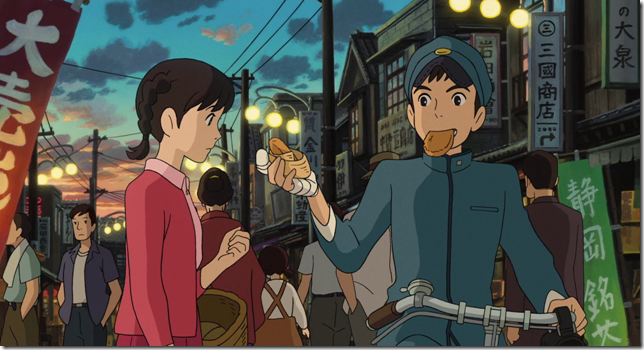

From Up on Poppy Hill: Goro Miyazaki, son of celebrated Japanese animation auteur Hayao, worked from one of Hayao’s screenplays to direct his sophomore effort, 2011’s From Up on Poppy Hill (Cinedigm / Disney, $22.19 Blu-ray and DVD combo pack), set in Tokyo in 1963. In it, high-schooler Umi (voiced in the English dub by Sarah Bolger) is forced to run a bustling household of siblings and boarders while her mother studies in America. Her father, a Navy captain, is believed to have perished in a war.

Her already hectic schedule is amplified further when she befriends a radical male student, Shun (Anton Yelchin), the school newspaper editor whose latest cause involves saving the campus’ Latin Quarter – a ramshackle clubhouse full of nerdy, curricular pursuits – from demolition. But the main conflict is one of heritage, as Umi and Shun, who are growing close as romantic leads, realize they may have been fathered by the same missing person.

From Up on Poppy Hill moves with the jubilance of a pop musical; the characters never break out in song, but you often expect them to. It’s frequently laugh-out-loud funny, particularly when breaking down the offbeat hierarchy of the Latin Quarter and its misfit specialists in philosophy, astronomy and communications.

It’s no surprise the film’s witty screenplay is its strongest asset. While Miyazaki keeps this touching film moving at an agreeable pace, he lacks his father’s poetry and profundity. Unlike Hayao’s best work, it doesn’t resonate beyond its time and place.

Three Worlds: At its best, Catherine Corsini’s Three Worlds (Film Movement, $21.99) plays like a Dardenne Brothers morality drama, without the formal rigor but with much of the disquieting intensity.

The three worlds of the title collide in the form of a hit-and-run accident: Two weeks before his marriage, Al (Raphaël Personnaz) the young scion of a French car dealership, strikes a Moldavian illegal immigrant with his car and flees the scene, but not before Juliette (Clotilde Hesme), an unmarried pregnant woman having problems with her boyfriend, witnesses the crime from her condominium window. She befriends the victim’s wife Vera (Arta Dobroshi) and eventually discovers Al’s identity, acting as both love interest (for Al) and unwitting interlocutor between both the perpetrator and victim’s family.

The three worlds of these characters represent varying economic strata, as well as cultures and philosophies, and the film potently addresses issues including immigration and health care while painting all three of its characters into troubling ethical corners. Everyone is flawed under Corsini’s lens, and nobody is demonized in the film’s complex web of blame, guilt, transference and hope for redemption. Despite all of this, while it would be harsh to say Corsini’s film loses its way in its home stretch, the writer-director seems to run out of ideas and conflicts in what is an initially captivating triangle. Even then, the committed performances shine through.

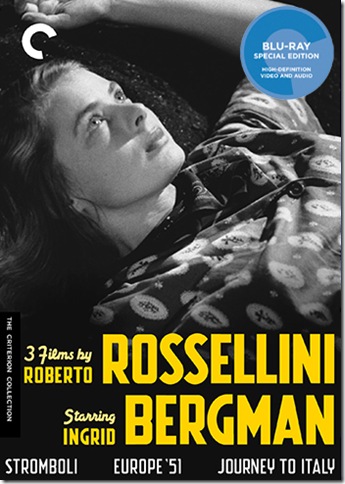

3 Films by Roberto Rossellini: Lastly, though it arrived in my mailbox too late for a full review, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Criterion’s 3 Films by Roberto Rossellini collection ($58.99 Blu-ray, $54.49 DVD); it might be the most important boxed set of 2013.

Specifically, the set focuses on the Italian maestro’s three controversial collaborations with Ingrid Bergman, his muse and co-conspirator in scandal-sheet domination in the early 1950s. Bergman became a fixture in Rossellini’s transition from neorealism to a cinema of poetics, and for the actress, these films represent art imitating life. In Stromboli, Europa ’51 and Journey to Italy, the Swedish-cum-Hollywood star finds herself adrift in foreign places, forced to adjust to strange new paradigms and situations. All three have earned canonization as some of the greatest films of all time.

What makes this set really worth investing are the copious extras, including both English- and Italian-language versions of two of the titles; The Chicken, a 1952 short-film collaboration between Bergman and Rossellini; Rossellini Under the Volcano, a 1998 documentary about the making of Stromboli; new video interviews with Isabella Rossellini and Martin Scorsese about Rossellini’s work; a 1995 documentary about Bergman; My Dad is 100 Years Old, a terrific 2005 Guy Maddin short starring the female Rossellini; and much more. There’s enough material her for a very rainy day – or, more accurately, six or seven of them.