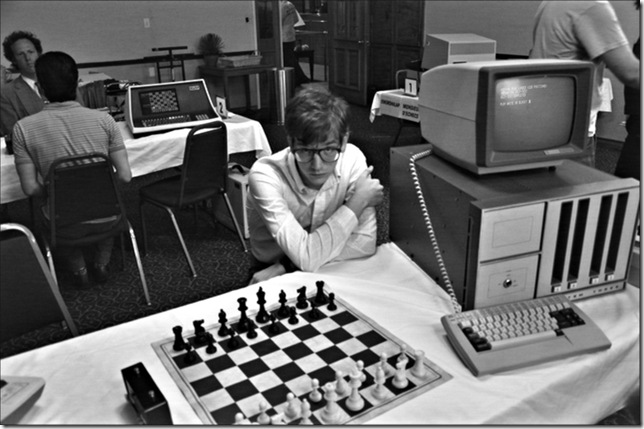

Computer Chess: The very fact that Computer Chess (Kino Lorber, $22 DVD) exists is an inspiration. The film is proof that a black-and-white experimental film —bdirector Andrew Bujalski called it an “existential comedy” — with no stars and the geekiest subject matter imaginable can still make nearly $100,000 at the box office. Which doesn’t sound like a lot until you consider that the movie feels like it was shot for a few hundred bucks over a weekend at a Days Inn.

Computer Chess is set, presumably, in the late ’70s or early ’80s, and it follows a group of programmers competing in an artificially intelligent chess tournament — their bulky hardware directing them where to move which piece — with the winning computer receiving the honor of playing against a flesh-and-blood chessmaster. What looks today like ancient tech history is treated appropriately as the cutting edge of technological innovation, and like most computer geniuses, the people that inhabit Computer Chess are sufficiently asocial, bearded, bespectacled, borderline autistic, barely functioning young white men — and one “lady,” from MIT, who is the subject of much novelty and intentional or unintentional sexism from her male cohorts.

The movie is presented like a documentary, but it’s nothing like Christopher Guest’s star-studded pseudo-docs, which no one would ever buy as the Real McCoy. Bujalski shot the film on video camera that dates back to the time of the movie’s setting — a Sony AVC-3260 vacuum tube camera — and the film is as much about the early days of video as it is computing. In an age of breathtaking high-definition, Computer Chess has all the resolution of a gas-station surveillance camera from the mid-80s. Moreover, Bujalski’s images are full of smears, glitches, fuzz and other visual static, giving the aesthetic of unrestored found footage unearthed directly from the period.

This movie is always strange and it’s frequently funny, its discomfiting humor of a piece with Bujalski’s s previous masterpieces, like Mutual Appreciation. But it’s never just those things; Bujalski’s form always comments on content and vice versa, whether it’s the director mercifully cutting away from pathetic conversations mid-sentence, or the camera suddenly adopting the point of view of a tubular monitor, or the particularly bizarre aside in which footage of a wayward character is replayed again and again, in color no less, like an endless cycle at the end of a stalemated chess game. The end result is a low-tech meditation on high-tech pioneering at the dawn of the Singularity, and he saves his best and most prescient joke for the very end.

Tokyo Story: “Life is disappointing, isn’t it?” This line, delivered with matter-of-fact acceptance toward the end of Yasujiro Ozu’s most acclaimed masterpiece, sums up its tragic pathos and its perceptive critique of the modern family. Available on a ravishing new Blu-Ray/DVD combo pack from Criterion ($33.96), Tokyo Story has never looked better on television, with the visual clarity adding more depth to this modernist masterwork, revealing every contour of the director’s precise frames. Tokyo Story is a cinematic feast and a showcase for the director’s singular mastery of interior space and his arrestingly direct photographic style, and its narrative grows ever more truthful and shattering the older the film, and its audience, gets.

It follows two elderly parents, living in rural Japan, who travel to Tokyo to visit their three grown children, none of whom give them the time of day, preferring to shirk their filial duties to their late brother’s widow, who seems to be the only person with any compassion for the agreeable elders. Tokyo Story is about the inevitable drift of children away from their parents, and the self-centeredness that overtakes their daily, busy lives. We don’t want to relate to the grown children, but most of us probably do, and it stings to watch.

Most of the characters bury themselves in regrets and perceived failures at one point or another, and there is much wisdom in their ruminations. It’s the kind of the film that should, and surely has, changed lives by reorienting our pyramids of importance. This box set includes an indispensable commentary track by Ozu scholar David Desser, who breaks down the movie shot by shot, along with a two-hour documentary about Ozu’s life, a tribute to Ozu featuring interviews with other world-class directors, and many more delectable extras.

Blackfish: Gabriela Cowperthwaite’s documentary about killer whales, SeaWorld and the issue of captivity (Magnolia, $22.93 DVD, $19.99 Blu-ray) comes across more as a biased advocacy picture than an example of objective reportage, but there’s reason for that: Nobody at SeaWorld would agree to be interviewed. It’s difficult, after all, to defend the indefensible.

Cataloging attacks from captive orcas over the past 30 years — with particular focus on Tilikum, SeaWorld’s most aggressive “entertainer” — Cowperthwaite builds a persuasive case for deleterious effects of killer whale captivity, with whale experts, scientists, activists and former trainers offering lacerating condemnations of a certain theme park in Orlando. The filmmaker takes time to explain the intelligence and sociology of these gentle (when in the wild) giants, so that by the time we hear about the injustices the whales endure in their concrete enclosures, it sparks the sort of outrage civil-liberties advocates would excoriate if they were perpetrated on humans.

The unseen SeaWorld managers come off as perjuring, deliberately deceptive profiteers, and the former trainers come off as whistleblowers who have finally seen the light. Blackfish is a heartbreaking and masterful bit of agitprop, and as a piece of entertainment, it’s also an uncomfortable, cringe-worthy thriller, with the director showing us a bevy of official attack videos — thus bringing an element of voyeuristic horror to a cerebral issue.

Hannah Arendt: Margarethe von Trotta directed this dramatization of a tumultuous period in the life of the titular German-Jewish philosopher (played by Barbara Sukowa), and it is bound to go down as one of 2013’s most underappreciated films ($29.99 Blu-ray, $23.99 DVD). Entering her twilight years and teaching comfortably at the esteemed New School in New York City in the early ’60s, Arendt proposes a series of New Yorker articles on the historic trial of Nazi war criminal Adolph Eichmann in Jerusalem. Her articles and subsequent book, which refused to demonize a man who was just “following orders” — for Arendt, Eichmann epitomized her famous theory of the “banality of evil” — and which placed some culpability on Jewish leaders who allowed the Holocaust to happen, caused a stir that torpedoed her reputation among her Zionist colleagues and many Jews across the globe, even leading to death threats.

Von Trotta’s film dives headlong into the cruel, intellectual muck of it all, and its depth is bottomless, addressing such themes as the subjectivity of “facts” in journalism, the compartmentalizing of evil deeds, the nature of power and responsibility, and, for the somewhat martyred Arendt, the way blind patriotism can cloud all nuance and breed its own sort of fascism (Jimmy Carter suffered a similar media backlash by the world’s Likudniks after publication of his 2007 book, Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid). But you don’t have to agree with Arendt’s position to admire von Trotta’s film; what makes it so intensely watchable are its crackling debates about the issues, which represent all sides with focus and clarity.

Broken: A sort of British American Beauty, Broken (Film Movement, $19.25 DVD) spirals even further into the heart of suburban darkness than Sam Mendes’ colorful Oscar winner. Broken is all-around bleaker, from its lower-middle-class neighborhood — situated next to an imposing junkyard, with its accumulating collection of automobile corpses — to the matter-of-fact violence of its harrowing narrative.

It’s essentially a coming-of-age story about a lovely diabetic girl (played with astonishing naturalism by a nonprofessional, Eloise Laurence, in her film debut), who is being raised by a single father (Tim Roth) and a nanny (Zana Marjanovic) whose relationship with a young schoolteacher (Cillian Murphy) provides both drama and nurturing in her life.

Then there’s the mentally unstable neighbor, the nubile slut with a big mouth, and the slut’s loose-cannon father, all familiar tropes from American Beauty shot through with crystalline precision. These lives converge in an intimate quilt of communal despair, with director Rufus Norris tailoring his camerawork in stylistically jarring ways when entering these characters’ varied headspaces. The movie is often disorienting, with Norris eschewing establishing shots and comforting transitions, instead hurtling from one climactic exchange to another. Once you find the groove of this film, its bothersome rhythms become visceral and moving.

Passion: In remaking Alain Corneau’s three-year-old French thriller Love Crime, Brian De Palma does more than assume authorship of the material in his 2013 version, retitled Passion ($16.97 Blu-ray, $14.96 DVD). He turns the film into a veritable repository for his own passions, neuroses and stylistic signatures culled from his 40-plus-year oeuvre.

Twin sisters? Check. Dramatic scenes in elevators and staircases? Check. Wigs, voyeurism and Hitchcock idolatry? Triple check. Complicated tracking shots, split screens and canted angles are present as well, in a story about a ruthless and kinky advertising executive (Rachel McAdams), her naive assistant (Noomi Rapace) and the increasingly deadly games that transpire between them.

Both actresses play awkwardly against type — Rapace, aka the girl with the dragon tattoo, is lethargic as a prim Minnie Driver archetype — and it’s charitable to say that neither delivers her best work here. In fact, the whole adventure starts off as stiff and uncomfortable as the non-sex scenes in a porn film, and only after an hour does it become a mesmerizing feast, with the director turning his elegant construct into an askew psychodrama. It may be De Palma’s most self-referential work yet, and for fans of his meretricious style, it ends up being great fun.

Thirteen Days: Nine years after Oliver Stone’s JFK, Kevin Costner once again surrounded himself in the Kennedy mythos, playing the president’s special assistant, Kenny O’Donnell, in Roger Donaldson’s Thirteen Days. Reissued on Blu-ray (New Line Home Video, $14.99) as part of the media bonanza surrounding the 50th anniversary of Kennedy’s assassination, Thirteen Days dramatizes the fortnight in 1962 when the U.S. and Russia narrowly averted nuclear war over the discovery of functional warheads in Cuba — in short, the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The film’s structure is straightforward, linear and episodic, with minor victories bleeding into new crises. It’s paced very well, but Donaldson is an anonymous visual stylist, and his film is edited with the empty fluidity of a Steven Seagal picture, using an obtrusive score to artificially heighten scenarios that are inherently suspenseful. Moreover, most of the action takes place among in the halls, offices and war rooms of the White House, and each dialogue-heavy set piece has the formality of an old play, where everybody politely waits for their colleagues to finish their points before making their own; time and again, one wishes for the overlapping chaos of Robert Altman’s direction. Donaldson occasionally switches from color to black-and-white, even mid-scene, a distracting device that has the unfortunate affect of conjuring Seven Days in May, a better movie than this one.

Thirteen Days is filled with unabashed reverence for Kennedy and the office of the presidency in general, with the cynicism of most modern political movies replaced by an old-fashioned romantic grandeur. This results in much sentimental filigree, including gravitas-laden platitudes and shots of tossed footballs and morning in America, coloring the sun-dappled breakfast table of a good churchgoing family. The movie is certainly star-spangled, if not jingoistic, but it’s an engrossing two and half hours nonetheless, a calculated study in sustained tension that believably re-creates a scenario where a single errant gunshot on a small island could trigger World War III.

Kennedy’s cool under pressure comes off as nothing less than miraculous. It’s hard to believe that our president today wouldn’t buckle under the pressure of a militaristic Pentagon and rush us into war if confronted with the same situation, and you can say the same for any of our presidents since Carter. This message of peace triumphing over knee-jerk war, more than any other, will ensure that this wobbly historical drama will always have legs.