You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet: You can’t watch Alain Resnais’ You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet (Kino Lorber, $27.98 DVD) without thinking of the very first full line of dialogue spoken in a motion picture: Al Jolson’s boast that “you ain’t heard nothin’ yet” in 1927’s The Jazz Singer. As befitting its title, the innovations in Resnais’ singular new movie are more visual than auditory, with the director playing with filmic space, split screens, irises and pictures-within-pictures in way that both harks back to silent-era innovations as well as exploits the limitless possibilities of today’s digital effects.

The movie’s plot, inasmuch as it has one, involves a menagerie of French movie stars young and old—among them Michel Piccoli, Sabine Azéma, Lambert Wilson and Anne Consigny—summoned to the cavernous manse of a newly deceased young theater director. He tells them, via a postmortem video message, that he wants them all together to view rehearsal footage of a local company’s version of his Eurydice, and then approve or disapprove the rights.

The gathered actors have all played parts in this director’s Eurydice before, many of them the same chief characters. And as they watch the footage, sense memory triggers visions of their old productions, and they “act out” the classic myth in their own styles, which eventually flood the film and overtake the video-within-a-movie (it’s all in their heads; in reality, they never leave their seats).

You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet is more engaging intellectually than emotionally, and I’m sure many of the film’s nuances are lost on non-French speakers. But Resnais directs this strange experiment with such hypnotic command that its two hours move quickly. The word “ghost” comes up a lot, as the actors’ visions for their Eurydice flit across the screen like the spirits of productions past, set against deliberately artificial, dreamlike sets and characters that materialize and dematerialize when needed. The ludic vintage he brought to films like Same Old Song and Not on the Lips takes an even headier bent here, lushly married to the plastic, saturated lighting with which he infused his Wild Grass.

Moreover, Resnais’ success at keeping straight his Altmanesque stable of stars is remarkable, not in the least because he’s 91 years old. If You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet is a self-reflexive meditation on the nature of interpretation, then Resnais is like the conductor of multiple symphonies all playing the same composition simultaneously. Like Jolson’s iconic ad-lib, it’s something we truly haven’t seen before in movies.

Far From Vietnam: Here’s a fascinating Sixties curio brought back from the dead by Icarus Home Video ($26.98 DVD). In this omnibus manifesto, from 1967, seven major filmmakers take on different aspects of the American intervention in Vietnam as it is happening, both on the home front and abroad. The result is a politically charged variety show, a smorgasbord of styles and voices—Godard, Resnais, Chris Marker and Claude Lelouche among them—mostly reinforcing the same perspective, which is now a widely recognized if inconvenient truth: that the U.S. acted as a terrorist nation in an unjust and horrific war, slaughtering countless innocent civilians in the process.

The film’s episodes are, mostly, not identified by director, but they are all compelling, from an inspiring and heartbreaking story about an American serviceman who self-immolated in front of the Pentagon to protest the war; to a painful, silent montage of Vietnamese corpses extracted from rubble, shot in flickering black-and-white; to a profoundly insightful monologue by actor Bernard Fresson, in which he addresses the impact of television on our perception of warfare, the trauma of past conflicts encroaching on new ones, the ease with which the oppressed can become the oppressor, and other topics.

Other tapas include a short interview with Fidel Castro about guerilla warfare; an appearance from folksinger Tom Paxton, who performs his protest classic Talking Vietnam Potluck Blues, set to these filmmakers’ documentary footage; and some audio and visual dispatches from an antiwar journalist who spent three weeks in the war-torn country. The most idiosyncratic segment of Far From Vietnam is, unsurprisingly, from Godard, who uses the opportunity to riff on cinema itself while candidly reflecting on his own empty notions of solidarity, as spoken from his perch in the cloistered community of French culture.

For my money, the most enduring portions of Far From Vietnam are the ones that are, well… quite far from Vietnam, on the streets of New York, where the directors capture a jingoistic pro-war parade — it’s no surprise that the showcase of faces selected for this segment resemble Diane Arbus grotesqueries — as well as the largest antiwar rally ever assembled. The latter yields indelible images of dead-baby art installations and provocative performance artists, as well as some heated confrontations with the war’s supporters.

You get the feeling the filmmakers lingered here the most because the streets of New York in the ‘60s were an exciting place to be, teeming and seething with opinions, at least half of which were uneducated ones. The right-wing xenophobia that excretes from some of the specimens in this film sounds identical to much of AM talk radio today.

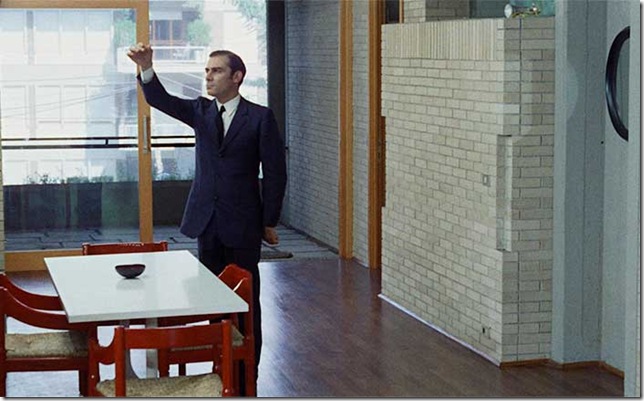

Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion: In the very first shot of this Oscar-winning Italian import from 1970 (Criterion, $25.98, Blu-ray + DVD), a man grins mischievously into the camera as he strolls toward an apartment complex. We don’t know anything about him yet, but he’s already implicating us — treating us as his accomplice in the crime that will instigate this crazy film.

Within a few minutes, he’s murdered the scantily clad sexbomb who lives in the opulent apartment, a woman with whom he’d been enjoying a perverse affair. Shortly after that, he’s back in his car and pulling into the parking garage where he works: as the homicide chief for the police department. He’s about to be promoted to the political division, where he’ll investigate dissidents, but not until he’s dispatched to deal with one last murder — the one he committed and anonymously reported.

The irony is as thick as concrete, but there’s more to this character, and to the film’s radical director, Elio Petri, than the absurdity of a police chief investigating himself. The chief (who, to my knowledge, is never named) committed the murder to prove a point: that his position is above the law, and that no matter how much evidence piles up against him, he will never be accused of anything. Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion is equal parts potent social commentary, savage comedy and inherent mystery — which grows deeper the more flashbacks we encounter between the chief and his victim —t hat fills its script with surrealistic ruminations on the mechanics of murder.

It plays out like bastard love child of Hitchcock and Kafka, with a dollop of Poe’s guilt thrown in, all performed to a wonderfully loopy Ennio Morricone score. The excellent Blu-ray/DVD combo pack includes two feature-length documentaries (on Petri and on the lead actor, Gian Maria Volonté), an archival interview with Petri, and a 2010 interview with Morricone.

Sister: Morals and ethics, choices and consequences, parents and children: These themes resonate as deeply in Ursula Meier’s Sister (Kino Lorber, $27.98 DVD) as they do in the intimate dramas of the Dardenne Brothers, though manifesting in an admittedly more conventional shooting style.

The adolescent actor Kacey Mottet Klein, who first appeared in Meier’s intriguing 2008 debut, Home, still manages to bring the unselfconsciousness and emotional nakedness of a non-actor to his role as Simon, the 12-year-old breadwinner of his penurious family. He lives with his much older sister Louise (Léa Seydoux, who recently turned heads in Blue is the Warmest Color), a promiscuous waste of space; their parents are nowhere to be found, and Simon has contrived a number of reasons for their absence, a different one for every inquiry. He spends his days hanging around a Swiss ski lodge under the auspices of assisting tourists; really, he just uses his ski credentials to steal expensive sporting goods (and food for himself and his sister) and resell them to make ends meet.

A revelation halfway through the film changes the dynamic and hurtles the story into tragic proportions, coloring much of the previous action in a darker hue. Just witness the difference between Simon and Louise’s playful wrestling, early on, and the bloody fight in the snow that comes much later. “I’m all alone,” Simon says, at one point, his head resting on Louise’s belly, a privilege that cost him a lot of money, because even love is negotiable.

Both of these characters are terrifyingly alone even when together, and Meier’s final image is heartbreaking—a parting shot that perfectly encapsulates this here-and-not-here dichotomy. Sister is Switzerland’s Academy Award entry for Best Foreign Language film this year; don’t be surprised if it makes the final cut.

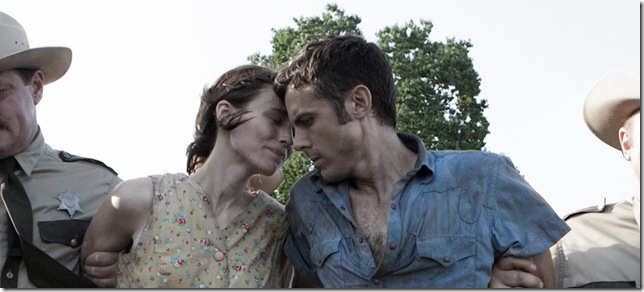

Ain’t Them Bodies Saints: What happened if, instead of becoming iconic outlaws, Clyde Barrow turned himself in after a botched Texas crime, leading to 25-to-life prison sentence, and leaving pregnant Bonnie — who actually fired the gun that led to the arrest — in the lurch?

That’s pretty much the premise of writer-director David Lowery’s atmospheric neo-Western (MPI, $21.23 DVD, $14.99 Blu-ray). The above action takes place in the first 15 minutes, but the rest of it jumps out four years in reel time, where the imprisoned outlaw, Bob Muldoon (Casey Affleck) has finally busted out of the hoosegow and is making the long journey home to his beloved, Ruth (Rooney Mara). Everybody wants him dead or recaptured, not the least of whom are the people who have grown closest to Ruth and her child: Patrick (Ben Foster), a steely police officer, and Skerritt (Keith Carradine), a sympathetic shopowner.

The movie’s course is a predictably tragic one, and Ain’t Them Bodies Saints has few narrative surprises up its sepia sleeves: The elliptical story has the momentum of predestiny, and because its actions are so expected, it never becomes emotionally gripping. Watch it instead for the score — an ambivalent ambient drone that frequently resists the urge to telegraph — and for the moody atmosphere.

Lowery is a painter of images, a descendant of Ford and Malick, and a master of capturing sunlight glinting off pastoral landscapes seemingly untouched by capitalism. The cinematography, which won an award at Sundance 2013, looks beautiful on this Blu-ray, which is inexplicably cheaper than the DVD release.