Late Ray: Satyajit Ray, India’s greatest world-cinema export, is most known for the flurry of raw but beautiful films he made in the ’50s and ’60s, such documentary-like rebukes to glossy Bollywood formula as Pather Panchali, The Music Room and Charulata. But he continued to direct films well up to his death in 1992, contributing new pieces to his humanist puzzle of Indian life despite his own ailing health. Most of these are unavailable on Western home video, but luckily Criterion has helped fill in this major late-period gap with its box set Late Ray ($35.02 DVD), which compiles three of his final four films.

The Home and the World, from 1984, pivots on a familiar Ray theme: An Indian woman’s self-actualization in a patriarchal society. A nonactress named Swatilekha Chatterjee, in her only movie, plays Bimala, an intellectual if romantically naïve young woman wed to the maharaja Nikhil (Victor Banerjee) in an arranged marriage. She’s been a kept woman, prohibited from exiting the gilded quarters of their inner palace, until Nikhil’s college buddy Sandip (Soumitra Chatterjee) shows up for an important visit. He’s in Nikhil’s village to preach a nativist political ideology, conveying an extreme anti-globalist message with the charisma of a cult leader.

Bimala, who is finally “released” to meet Sandip, finds him fascinating — and he finds her positively rhapsodic, his muse in the revolution. She quickly learns that Sandip and Nikhil are on opposite sides politically, with Bimala torn between them in more ways than one, even as Sandip’s seemingly good intentions grow more nefarious with each round of opposition he faces.

The Home and the World is a cautionary tale, and not a particularly subtle one, about the mesmerizing power of propaganda. Ray scripted the movie from Rabindranath Tagore’s novel, and it feels like a filmed book, for better or worse: It has the lyrical sweep of quality Merchant Ivory, but it’s also burdened with the didactic tendency to overexplain and underline. And its lapses into sentimental melodrama are thankfully absent from Ray’s earlier masterpieces.

Still, for a 138-minute feature set almost entirely in private chambers, The Home and the World moves at an enviably engrossing pace, and it uses its heft to present a complex world sensitive to issues of religion, class, politics and love in not-too-distant India. Its first half, at least, reaches toward mastery.

“The honest always suffer the most,” according to a character in Ray’s 1989 drama An Enemy of the People, an idiom that bears itself out in this righteous adaptation of the Henrik Ibsen play of the same name. In Ibsen’s text, a crusading doctor discovers that a lucrative new bathhouse proposed by his city is infecting its visitors with contaminated water, but is soon marginalized and silenced by the business community.

In Ray’s film, the doc, Ashoke Gupta (Ray regular Soumitra Chatterjee), has a more intimidating hurdle to jump: the religious and political interests in Chandipur. When his evidence suggests that the holy water in the municipality’s largest temple is the cause for many new cases of jaundice, his brother the municipal chairman—another example of the personal becoming the political—does everything in his power to prevent the message from reaching the populace, including convincing a callow “progressive” newspaper editor to retract his support for Gupta.

An Enemy of the People doesn’t seem to be inspired by a real case, but it certainly could be, in any town where religious hysteria trumps science. This talky film has its faults; Ray was recovering from a heart attack during the shoot, and he was ordered to limit his mobility and shoot only indoors. Thus, An Enemy of the People feels stagebound and contains little cinematic beauty. Also, it loses some of its tragic impact thanks to a softened denouement. But this polemic is certainly eloquent and aimed at the right targets. If seen by more people than its marginal release allowed, it could have shaken people up; perhaps now it finally will.

But this collection saves the best for last — that being Ray’s exquisite 1991 swan song, The Stranger. It’s no less dialogue-driven than An Enemy of the People, but every frame feels alive, and Ray’s humanism toward everyone in the story is on vivid display. It opens with Anila Bose (Mamata Shankar), the well-off housewife of a small, well-to-do Indian family, receiving a letter from a man claiming to be her long-lost uncle, who left the family for a nomadic life 35 years ago, when she was 2 years old. He wants to stay with them for a while, beseeching her with traditional codes of Indian hospitality. But her husband, Sudhindra (Dipankar Dey), suspects he may be an imposter, or else harbor ulterior motives for his sudden reappearance.

The “uncle” (Utpal Dutt) soon arrives at their doorstep, and so begins a series of gradually revealing — and occluding — conversations that suggest he’s telling the truth while planting occasional seeds of doubt. The Boses call on a number of friends and colleagues to discreetly interrogate their new houseguest, each of them a test of his veracity. He talks often of the sun, the moon and solar and lunar eclipses, which symbolize this ludic film’s intention to reveal and cover up, keeping the mystery alive until the very end. The Stranger is about a quest for authenticity in an uncertain world which Ray would depart a year later, and in terms of cinematic truth, his final statement bristles with unvarnished reality.

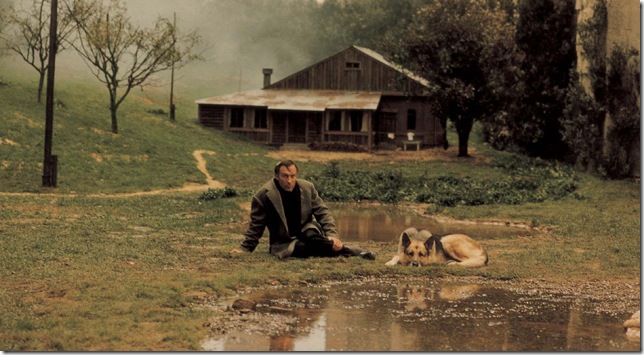

Nostalghia: Andrei Tarkovsky’s penultimate feature, from 1983, finds the Russian master in a particularly introverted mode. Available for the first time on DVD and Blu-ray in the U.S., Nostalghia (Kino Lorber, $26.68 Blu-ray, $24.33 DVD) is a virtually plotless, experimental ramble through Tuscany’s ancient architecture.

It’s here that Russian writer Andrei Gorchakov (Oleg Yankovskiy) is visiting, with a beautiful interpreter in tow (Domiziana Giordano), to research the life of a famous poet. But he’s soon sidetracked by a fascinating lunatic/prophet, Domenico (Erland Josephson), who once locked his family in an underground bunker for seven years because he foresaw an apocalypse that never came.

In the film’s universe, Domenico is a local pariah, but today, of course, he’d land his own reality series. As for Andrei, he’s as stuck in the past — his regretful memories rendered in painterly black-and-white, jarringly intruding on his journey — while Domenico is stuck in a futureless present.

Among other things, Nostalghia seems to suggest that time and space are immaterial notions in the grand scheme of creation, and that the line between the insane and the faithful is an invisible one. But it’s ultimately a head-scratcher, one of the director’s most naval-gazing and intransigent pictures. Just about every line of dialogue is cryptically weighty, a profound musing projected into the ether before quietly evaporating. The whole thing is as playful as a holocaust. Unlike Tarkovsky’s best films, like Stalker and Ivan’s Childhood and Solaris, watching Nostalghia feels like work.

But even the most alienating Tarkovsky film is more interesting than 90 percent of movies, and Nostalghia offers a characteristically Herculean feast of extended takes, which preserve the integrity of his precise compositions. Every frame is an artistic tableau, every bit of color, or lack thereof, signifying something, every cut—and there aren’t many—a personal statement. The languorous tracking shots will stick with you, even if the film’s overriding meaning remains elusive.

Hail Mary and For Ever Mozart: Good on the Cohen Media Group for respecting the wishes of Jean-Luc Godard completists and releasing, on ravishing Blu-rays, two films from the director’s most ornery and challenging period ($34.99 each). These aren’t the Godard movies you’re likely to see on TCM or in film classes or retrospective series, but in many ways they’re more mature than his early, iconic shots from the bow of the Nouvelle Vague.

Liberated by time and loosened social mores, 1985’s Hail Mary — a film once decried by Pope John Paul II, and which earned Godard a pie in the face at the Cannes Film Festival — today looks like an essential exploration of a theistic phenomena. It dramatizes the life of a modern-day “Mary,” who works at a Swiss gas station and finds herself pregnant, even though she’s a virgin—a development that disturbs her boyfriend Joseph and confounds her doctor.

For a movie that is ostensibly sacrilegious and that contains much-ballyhooed full frontal nudity from actress Myriem Roussel, Hail Mary is actually one of the most beautiful spiritual experiences ever wrought on celluloid, up there with Dreyer’s Ordet. Perhaps its actualization of a bona fide miracle, freed as it is from the strictures and guidance of organized faith, was too much of a religious experience even for Christians. This is an utterly gorgeous film that is chockablock with ideas.

The same can be said for 1996’s densely packed For Ever Mozart, but exactly what its disparate ideas add up to is anybody’s guess. The episodic film, whose thesis may be summed up in one of its earliest quotes—“36 characters in search of history”—is divided into fragments which comment on the making of art, from a radical theater troupe whose attempts to stage an Alfred de Musset play in Sarajevo run headlong into armed conflict; to an elderly, dictatorial director trying to complete a doomed film. The characters are less flesh-and-blood people than mouthpieces for philosophical discourse, both timeless and contemporaneous to world affairs.

Along the narrative’s unpredictable rivulets, we’re treated to allusions to Miguel de Cervantes, Albert Camus, Che Guevara, Victor Hugo and John Ford, a veritable Rolodex of Godardian sociopolitical touchstones. With its string of explosions and gunfire, For Ever Mozart may be the closest thing Godard ever made to an action movie, though much of the film seems to be commenting on the vacuity of blockbusters. It’s funny but acrid, and its loose ends join only in Godard’s scattered head.

Rewind This!: Being a natural born hoarder — albeit a highly functioning one — I was one of those people who held on to his VHS tapes longer than I should have. I’d probably still own them now were it not for the issue of the cropping and pan-and-scanning of the format’s boxy aspect ratios, which helped kill the mass medium for dedicated cinephiles. But there remain plenty of devotees to the 187mm-wide, 25mm thick plastic rectangle, as this affectionate documentary by Josh Johnson (MPI, $22.28 DVD, $35.98 for DVD+VHS combo pack) explains.

It contains interviews with filmmakers, actors and distributors whose lives were vastly improved by the development and widespread acceptance of the VHS tape, but its most colorful vignettes explore the collectors working to keep VHS out of the dustbin of movie history, whose homes contain shrines-cum-mausoleums to analog movies: thousands-plus walls of tapes, sometimes alphabetical, sometimes organized via the colors of their box art or by fastidious micro-genres (one collector has amassed films around topics like “pre-sellout Craven.”)

Johnson is evenhanded about his survey of VHS’s impact, which everybody agrees democratized movies away from studio dictates and created personal choice among moviegoers. But his subjects note that its picture quality was inferior even to Betamax, let alone laserdisc and DVD, and that it won international acceptance because — surprise! — audiences didn’t notice or care.

The aspect ratio issue is addressed as well, and it’s not a shocker that Johnson finds no collectors who cherish old VHS tapes of Bergman and Bresson titles, for instance; instead, the story of VHS revivalism is really the story of B-movie schlock, of a community coalescing around Good Bad Movies they can’t accrue on any other format, because what modern distributor would release them?

Even with this overarching statement — “Criterion, go f*** yourself,” says Frank Henenlotter, director of the beloved VHS horror-comedy Basket Case — Rewind This! comprehensively uncovers one thematic rock after another, from the medium’s immediate impact on the adult film industry to the format’s ability to inspire home-movie auteurs to the cultish future of a medium everybody thought was dead. By the time one avid collector discusses the philosophical underpinnings of the ubiquitous tape instruction “Be kind, rewind,” you may be convinced to drive to your local Goodwill and spend five hard-earned dollars on a secondhand VCR.

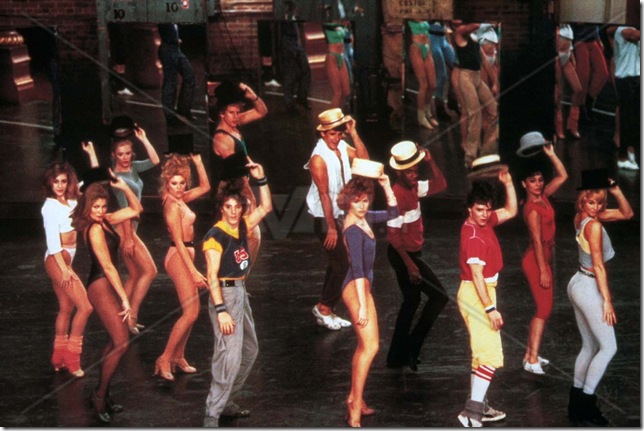

A Chorus Line: Released in 1985 and reissued recently on Blu-ray (Fox, $16.18), Richard Attenborough’s adaptation of A Chorus Line has suffered a maligned reputation from theater purists, and it almost goes without saying that the visionary stage musical is less effective as a film.

Some of the dance numbers, particularly the cinematic additions, are stretched beyond tedium and set to woefully dated music; and without significant changes to the show’s formula of a row of chorus wannabes sounding off about their lives, it’s hard for Attenborough to shed its highly theatrical conceit.

The one major difference is that screenwriter Arnold Schulman foregrounds the relationship between choreographer Zach (Michael Douglas) and Cassie (Alyson Reed), his ex-flame and a former star dancer relegating herself to a chorus audition. It’s an interesting choice that allows Attenborough the freedom to drift a bit from the show’s single setting, but it also disrupts the spirit of egalitarianism that I suspect the book’s original writers would have hated.

But if you’ve never seen A Chorus Line in any format, this movie is still a solid enough primer, effectively conveying, through its 16 individualized characters, the universal trials and tribulations of the lower rungs of show business: the nerve-rattling competitiveness, the asinine acting teachers, the sexism, the antigay prejudice, and the creeping sense that each job could be your last. Stick around to the very end for a stunning employment of CinemaScope photography, which looks beautiful in this Fox restoration.