Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson: This 1976 comedy by Robert Altman (Kino, $16.99 Blu-ray, $11.99 DVD) isn’t as poetic as his earlier ‘70s Western, McCabe and Mrs. Miller. But whereas that film explored capitalism through the prism of frontier life, Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson similarly employs Western tropes to comment on another modern American scourge: show business.

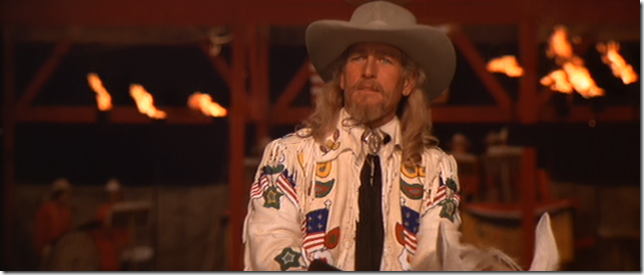

As adapted by Altman and Alan Rudolph from a play by Arthur Kopit, the Buffalo Bill in Buffalo Bill is a self-important huckster played by Paul Newman, whose product is himself — or at least the version of himself that he wants the public to remember. Wrapping himself in American flags, and with the help of sycophantic publicists and colleagues, he makes his postwar living by restaging his battles with Native Americans in a Wild West stage show, complete with bull wranglers and the sharpshooting skills of Annie Oakley (Geraldine Chaplin). In Bill’s jingoistic interpretation, the show always concludes in his rousing takedown of Sitting Bull, who is usually played by a black man — until the real Sitting Bull (Frank Kaquitts) expresses interest in his production, promising star cachet in return for demands that put green M&Ms to shame.

As always with Altman, there’s a lot going on under his eavesdropping lens, both in his gorgeous ‘Scope photography and in the film’s expansive thematic canvas. Buffalo Bill and the Indians addresses the vanities of celebrity and, in its bloodless negotiations and uneasy détentes between Bill and Sitting Bull, a potent metaphor for Cold War tension. But mostly, the film is a sly acknowledgment that the past is always subject to the interpreter, the storyteller, the ringmaster with the agenda —that history is written by the winners.

This observation would be meaningful enough to carry the film, but Altman goes further, finding the melancholic undercurrent that ebbs to the surface when Bill’s reality can’t match his legend. In the film’s masterful climax, Sitting Bull becomes little more than a hallucination representing Bill’s guilt and insecurities. Bill may always win when he’s playing with a trick deck, but his greatest fight remains against his own image.

The Night Porter: No actress — since at least the time of Bette Davis and Joan Crawford — can penetrate you with their eyes quite like Charlotte Rampling, who possesses the rare ability to turn colleagues and villains alike to mush with just one intimidating gaze. As Lucia, a socialist’s daughter imprisoned by the Nazis in World War II who discovers her abuser/lover more than a dozen years later, she’s wordless in her first scene in Liliana Cavani’s 1974 drama The Night Porter (Criterion, $22.49 Blu-ray, $16.99 DVD). But her concentrated stare is enough to suggest the entire complicated history she shared with Max (Dirk Bogarde), an SS officer now stationed as a porter in an upscale Vienna hotel.

Shadowy, deliberately paced and disturbingly erotic, The Night Porter is a perfect vehicle for Rampling’s ageless intensity, which manifests in both her mercurial, renewed relationship with Max and in fragmented flashbacks to her time in the prison camp, as a barely nubile girl in throng to a sadistic mass murderer. In one of the film’s many aurally ingenious touches, their relationship reaches literally operatic heights, as they share glances while in the audience at a production of The Magic Flute (Cavani received permission to film during a real-life Viennese mounting of the Mozart opera), whose music continues to swell and pulsate over carnal flashbacks that do much of the same on a visual level.

This scene exemplifies the many dichotomies that make the film so much more than titillating Nazisploitation: Pain and pleasure, fear and desire, filth and cleanliness, the past and the present coexist always in Max and Lucia’s sadomasochistic relationship — binaries that upend both of their lives, with tragic results. As the reunion progresses and Max’s SS colleagues seek to eliminate this final witness to his Third Reich atrocities, he holes up with Lucia in an apartment that becomes a prison.

He finally feels what it’s like to be a victim of persecution — pallid, starving and helpless, with armed enemies around every corner. Cavani achieves the seemingly insurmountable task of making us feel sympathy for a Nazi, a move that continues to divide critics. Decide for yourself in this rich Criterion transfer, which renders Alfio Contini’s expressionist cinematography more beautiful than ever.

A Thousand Times Good Night: Few moments in any 2014 movie are as affecting and disturbing as the first (and last) 10 minutes of A Thousand Times Good Night (Film Movement, $13.47 DVD), the third feature from acclaimed Norwegian director Erik Poppe (Trouble the Water). In these bookends, European war photographer Rebecca (Juliette Binoche), donned in a hijab, has penetrated a clandestine terror operation in Kabul, watching as girls no older than her own children strap explosives around their waists. In the first such instance, she remains embedded in the operation for longer than she should, and she is nearly killed in the blast. But what a moving, thrilling can of photos she returns with.

Poppe is most interested in the psychology and domestic reality of the dedicated war correspondent, a post he held before embarking on a feature film career. Back home, which constitutes the largest chunk of A Thousand Times Goodnight, Rebecca tries to readjust to a quiet life in her beachfront property in Ireland with her two girls and marine biologist husband Marcus (Nikolaj Coster-Waldau, of Game of Thrones). Her family members, justifiably, don’t appreciate her truth-telling sacrifice on the battlefield; they’d prefer their mother alive. But, like combat troops who have trouble returning to domestic minutiae, Rebecca lives for the thrill of conflict, to the extent that she only feels alive when she’s dodging bullets: While watching her flounder on the homeland, I thought, more than once, about arguably the best shot in The Hurt Locker, when Jeremy Renner stands, befuddled and alien, before a wall of cereal boxes.

A Thousand Times Good Night plays out like an addiction narrative, complete with attempts to go straight, relapses, broken promises and self-delusions. Except that this is a more complex addiction movie than most, because what Rebecca is doing is so vital to humanity — even if, as Rebecca points out, the populace is more interested in looking at Paris Hilton wardrobe malfunctions than war-torn children in Africa. Poppe pulls no punches in forcing his troubled protagonist to choose between two lives, even if it means disappointing audiences looking for a happy resolution — or any resolution at all, for that matter. Binoche’s performance brilliantly conveys her internal struggle in this daring and uncompromising feature, one of the most underrated of the past year.

Yentl: It’s still absurd after all these years, but Barbra Streisand’s labor of love holds up as an oddly prescient gender-bending curio (Twilight Time, $29.95 Blu-ray). Adapting and directing a play co-written by Isaac Bashevis Singer, Streisand casts herself as the title character, an aspiring Talmudic scholar in a patriarchal society —Ashkenazi Judaism in Poland, circa 1904 — who disguises herself as a young man in order to continue her studies at a yeshiva.

Her transformation is accomplished by doing little more than cutting her hair short; she inexplicably fools everyone for the next two ludicrous hours, while becoming smitten with her study partner, Avigdor (Mandy Patinkin) — whose fiancée, Hadass (Amy Irving), happens to fall for Yentl. This strange and complex love triangle is the strongest element of Yentl. Homosexual/transgender implications hide in plain view of an ostensibly hetero drama, providing a subversive and challenging backbone to what could have been presented as an unnaturally protracted farce.

The movie is also a musical, of course, with Streisand handling every lugubrious note and frequently stopping the narrative dead in its tracks. The album went platinum back in 1984, though today the songs are, to put it kindly, an acquired taste. Michel Legrand’s bombastic score is no better, leaving no emotion to the imagination.

Twilight Time, however, deserves singular praise for releasing what is essentially an immediate collector’s item (only 3,000 copies were printed), with a visual richness that exceeds that of most other Blu-ray remasters. Even if you’ve seen Yentl before, it may feel like you’re watching it for the first time, re-discovering the innumerable shades of brown with which cinematographer David Watkins painted his widescreen frame. The special features likewise transcend expectations, including an extended cut of the film, an audio commentary, an introduction by Streisand, deleted scenes and rehearsal footage, and even Streisand’s 8mm “concept film” complete with her narration.

Tesis: “Do you think a film can kill someone?” This question is posed in conversation by the protagonist of Alejandro Amenabar’s new-to-Blu-ray 1996 debut (Bayview, $24.99), but it’s posited more directly to us.

Angela (Ana Torrent) is a communications major preparing a thesis on audiovisual violence. Seeking torture porn for her academic study, she falls in with a campus outcast (Fele Martinez) with a limitless supply of graphic videos. Meanwhile, Angela’s professor and thesis supervisor drops dead of a heart attack while watching a snuff video he rented from an underground university library. When Angela and Chema discover the tape, it leads them toward a labyrinth of sordid secrets involving another cinema professor, a handsome amateur videographer (Eduardo Noriega) and a missing student.

Amenabar, who would go on to write and direct the international smash Open Your Eyes, knows his way around a good dream sequence, and there’s a thrilling one in Tesis, as well as a few aurally imaginative touches: When Angela and Chema meet, they’re listening to vastly different music through earbuds, and Amenabar jolts us between her classical and his heavy metal in series of escalating point-of-view intercuts.

The director successfully creates an atmosphere of palpable terror around every menacing corner, and despite the dated references to camcorders and floppy disks, its message transcends. This self-referential horror mystery is a savage commentary on horror cinema itself and the public’s universal desire to savor grisly images —even if it’s not lacking in its own conventional sadism; the climax of Tesis is particularly tawdry and implausible. Part Videodrome and part Nightcrawler, Tesis is the flawed but thoughtful debut of a film artist unsure if he wants to deconstruct establishment cinema or join it.