Life of Riley: Alain Resnais’s final film (Kino, $19.99 Blu-ray, $17.99 DVD), which premiered just three weeks before his death, is an effervescent comedy that sees the French cinema giant accepting his transition with grace, laughter and sardonic self-awareness.

Adapted from the English play of the same name by Alan Ayckbourn, it charts the machinations of George Riley, a forever unseen teacher in Yorkshire who is suffering from terminal cancer but has a few tricks up his sleeve for the friends he’s leaving behind: his ex-wife Monica (Sandrine Kiberlain), his best mate Jack (Michel Vuillermoz), his old flame Kathryn (Sabine Azema) and their spouses.

Known only by reputation, George takes on an otherworldly aura — tempestuous, charismatic, insatiable, Machiavellian — and he turns his friends’ world views topsy-turvy over the course of his final six months. His actions spur revelations of secrets both new and long-kept, prompting romantic and sexual confusion that ends up strengthening his friends’ marriages.

This is a clever idea in itself, but Resnais ups the ante, as was his wont in his final films, by treating all the world as a stage — a gauzy, artificial playground of possibility. All the characters except Monica are involved in the production of a play (called Life of Riley, natch) that, like George, we never see. But Resnais films the rehearsal space and domestic scenes against transparently plastic sets dotted with spiraling shrubbery and mechanical gophers, where thick, painted curtains substitute for the rolling hills of the English countryside.

Colorful, hand-drawn pictures of houses are employed whenever Resnais desires establishing shots, and when he cuts to a close-up, the character’s head is always framed in front of the same identical, patterned green-screen image, no matter where they’re standing in the scene. All of this ironic artifice is a cheeky way for Resnais to film an England-set narrative in French studios, but it’s also this great innovator’s final dig at the staid rhythms of traditional film grammar, calling attention to the old Godard quip that “every edit is a lie.”

Every image in Life of Riley is a lie, but the characters living them believe it, and so do we. Even in his last days, Resnais was inspiringly unbound from convention, teaching us one final lesson in humor and humility before settling, like George Riley, into his eternal rest.

Ride the Pink Horse: This film noir (Criterion, $27.59 Blu-ray, $22.99 DVD), released in 1947, takes a sabbatical from gritty urban streets and bleak, predestined outcomes. Instead, director Robert Montgomery, who also stars, imbues his movie with kindness as well as brutality. He contrasts morally bankrupt greasers in pinstripe suits with lives that are pure and incorruptible, resulting in one of the genre’s most poignant and underrated experiments.

Montgomery plays “Lucky” Gagin, a GI and small-time criminal who descends on a small Mexican border town to blackmail the corrupt industrialist who hired a hit man to kill his friend. Instead, he meets a colorful mélange of supporting characters that attempt to derail his mission or mold it for their own gain, including a slick, persuasive FBI agent seeking to arrest the same gangster (Art Smith); Majorie Lundeen (Andrea King), a femme fatale whom Gagin describes as having “a dead fish where her heart ought to be;” and Frank Hugo (Fred Clark), his unctuous target, who proves to be a more brutal adversary than expected. Though he tries to remain a lone gringo on a quest, a couple of Spanish-speaking locals befriend him — Wanda Hendrix’s impressionable teenage girl and Thomas Gomez’s good-natured barfly — and help to right his moral compass.

Time and again, Gagin seems on the brink of collapse, if not death, and Montgomery’s performance is so deeply felt it’s almost painful to watch, a notch above the requirement of most noir acting. The script, by the great Ben Hecht and Charles Lederer, contains plenty of fresh, pulpy wit, while Montgomery’s direction captures the local flair of the Mexican town with a genuine affection. The scene that gives the film its name, in which a man is beaten by thugs in the background while children gaze in horror from a moving carousel in the foreground, is disturbing and unforgettable.

Criterion’s transfer is lustrous as usual, and the extras include a radio broadcast of Ride the Pink Horse and an illuminating interview with Imogen Sara Smith, a scholar of unconventional noirs.

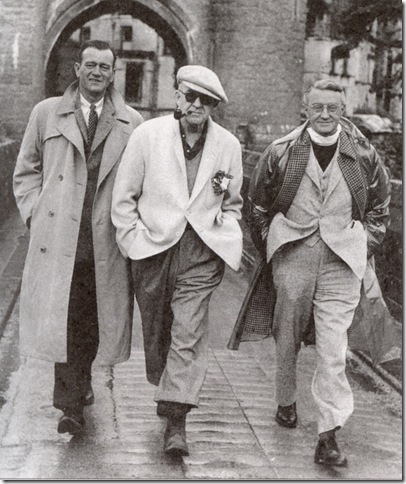

John Ford: Dreaming The Quiet Man: There may be no name more quintessentially American than “John Ford,” but even his nom de plume, like so many of his movies, was a legend.

Ford was born John Martin Feeney, to Irish parents, and a love for his heritage predated the Westerns and war pictures for which he is most known. He channeled all of his affection for a verdant and mythical Ireland into 1952’s The Quiet Man, an enduring labor of love that, as the scholars, directors, and cast and crewmembers interviewed in this documentary (Olive, $19.99 Blu-ray, $17.99 DVD) assess, is a singular title in Ford’s oeuvre.

Director Se Merry Doyle sets her doc in the time-warp village of Cong, the Irish town that doubled as “Innisfree” in Ford’s vision. Doyle found that the village, with its streams and ancient bridges, its castles and abbeys, is a shrine to the film that put it on an international map, a natural land untarnished by industrialization. The village had no electricity and one phone line, we’re told, when Ford’s crew descended on it to film a movie that was dismissed by the studio as “a silly little Irish story.”

Dreaming the Quiet Man is loaded with trivia like this — Maureen O’Hara discusses injuring her hand during an impassioned take with John Wayne, requiring a hospital visit and four days of recuperation — as well as deeper, more edifying analysis of the movie’s cultural peculiarities. There are also plenty of Quiet Man clips to savor, with Doyle selecting scenes that capture its beauty and aggression, its carnal pulse and its earthen pugnacity.

There’s a lot of fascinating and useful information in Doyle’s doc, but its straightforward, public-television-style presentation feels a little too conventional a celebration for a film this eccentric. The inevitable bagpipe music and the narration, by Gabriel Byrne, are unnecessarily sentimental. It certainly makes you want to re-watch The Quiet Man, but it’s not the Room 237 to The Quiet Man’s The Shining, even though you wish it were.

Pioneer: This troubling Norwegian thriller (Magnolia, $12.99 Blu-ray and DVD) from the country’s most well-known director, Erik Skoldbjaerg (Insomnia, Prozac Nation), is fact-based, so that even when it veers off-course, its patina of historicism almost keeps it afloat.

It’s set in the late 1970s, when oil and gas resources are discovered in the North Sea. Two brothers, Petter and Knut (Aksel Hennie and Andre Eriksen), are part of a binational initiative, along with an American corporation, to lay the nation’s first petroleum pipeline on the ocean floor, which involves a harrowing plunge into, literally, uncharted waters. When tragedy strikes the first test divers, Petter suspects the project managers are hiding something, and he spends the rest of the film risking his life to ferret out the truth.

Pioneer is never better than when it plummets into the abyss with its characters; rarely has the endless ocean felt so stifling and claustrophobic, so merciless and stomach-churning. Skoldbjaerg’s camera places us inside Petter’s head both underwater and above ground, where there really isn’t much difference — blurred visions, hallucinations and the tinny drones of controlled compression and decompression make us question reality just as Petter questions the company line.

Skoldbjaerg’s plotting isn’t as sound as his atmosphere, however. As Pioneer becomes a full-blooded conspiracy thriller in the paranoid vein of The Conversation and The Parallax View — complete with sundry collusions and cover-ups, cowed patsies and convenient deaths — the movie’s implausibilities snowball, and the fealty of its chilling early scenes is sacrificed at the altar of commercial expediency.

Skoldbjaerg spends so much of his 111-minute running time dancing around his mystery that when it’s finally revealed, our interest has waned. We’re left with a cynical conclusion that reiterates what we already know but that, admittedly, still sounds prescient in the ongoing battle over the Keystone Pipeline: fossil fuels are a dirty business.

Vincent and Theo: This underrated 1990 gem (Olive, $19.99 Blu-ray, $17.99 DVD) is a biopic the Robert Altman way — weird, drifting, shot through a barbiturate haze. Vincent Van Gogh’s life had been dramatized more conventionally in the classic studio picture Lust for Life, but Altman extends the tragedy of the self-destructive painter to include his brother, for whom he was connected in every way but Siamese.

We first encounter Vincent (Tim Roth) penniless and mooching off his more successful art-dealing brother Theo (Paul Rhys). By the end, he’s in the grave , and in the meantime we rarely see him making very much art. In fact, Altman dispenses almost entirely with state-of-the-art-world context: This is purely a personality-driven story of doomed siblings teetering toward madness, and it’s quite a showcase for its actors.

Roth, in particular, delivers an infernal performance of disgusting dedication, coloring his Vincent with creepy, rotten-toothed smiles and unnerving stares that hide animal urges. His encroaching mental illness is best conveyed in the movie’s signature scene, in which he stands in a field of sunflowers and destroys a landscape, while Altman’s camera weaves in and out of the floral tapestry like a paranoid prizefighter. It’s only after Vincent is institutionalized that his works seem to be gain any traction, a fact that wasn’t lost on Altman and shouldn’t be lost on any of us: Talent is fine, but madness sells.

Vincent and Theo has never been particularly difficult to obtain on home video, but as a roiling tribute to a painter who cared deeply about his colors, this gorgeous Olive Blu-ray is certainly the edition to own.

Believe Me: There’s plenty of profit to be made in the religion business, amen. This fact — institutionally hidden, universally acknowledged, but rarely presented in our popular entertainment — forms the backbone of Believe Me (Virgil, $12.19 Blu-ray, $9.96 DVD), a dark indie comedy that sounds provocative on the surface but reveals itself to be as mushy as tapioca pudding underneath.

Sam (Alex Russell), a leader of his college fraternity in Austin, contrives a fictitious Christian charity — Get Wells Soon — pretending to funnel funds to drinking water in Africa. He and his three co-conspirators in the frat — the token dimwit, the token sociopath and the token African-American with a conscience — intend to further the charade enough to raise money for their post-college plans. But it isn’t long until an enthusiastic head of a touring ministry (Christopher McDonald) listens to their ersatz message and signs them on for a nationwide fundraising tour.

The movie’s believability, despite its title, ends there. To continue with its charade is to accept that the founders of any nonprofit — genuine or otherwise — would make it past first base without showing any actual knowledge of their cause or any figures to back up their need. And if these guys make for transparently unconvincing Christians, the real believers in the movie come across as manipulable rubes, like the naïve victims of Bernie Madoff.

But the film’s biggest sin is that it squelches the bold deviousness of its own premise by providing Alex with his inevitable moral reversal — his Come to Jesus moment. It’s like an initially promising South Park episode that ends in Stan saying, “I’ve learned something today….” Only he really means it.