The Story of Adèle H: This haunting biopic from 1975 easily ranks as one of Francois Truffaut’s best films of the ’70s, and Twilight Time’s uber-limited, 3,000-copy Blu-ray transfer is a treasure to behold ($29.95). A 20-year-old Isabelle Adjani became the youngest actress at the time to earn an Academy Award nomination for her role as the title character, the damaged daughter of Victor Hugo, who pursues a former lover that’s just not into her and breaks down as a result.

The story begins in 1863 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where Adèle’s prey, a British lieutenant named Pinson (Bruce Robinson), is stationed for a possible entry into the American Civil War. She rooms in a boarding house under an assumed name, begs her wealthy father for money, and hires a notary public to track down Pinson, all while justifying her search with compounding lies and delusions. She becomes his shadow, lurking behind him always; in one mesmerizing scene, she spies on his tryst with another woman by creeping through the foundation of her chateau like a termite, gnawing closer and closer to the bedroom.

The magnificence of Adjani’s gradual unraveling cannot be overstated. She begins the film as a proto-Paris Hilton type, an entitled celebutante bored with privilege, annoyed by the slowness of her parents’ money transfers, beseeching them in letters for not publishing her music back home in Guernsey. The more the film progresses, the more she declines. Her hair becomes a rat’s nest, her faunlike facial features begin to resemble chipped plaster, and her dresses sit on her in tatters, until she’s little more than a numbed zombie without an appetite, a ghost still stuck in a useless body. We’ve seen bluebloods descend into madness before, but Truffaut takes no delight in Adèle’s crackup: This is a tragic story of unrequited love.

By 1975, Truffaut was by any account a mainstream filmmaker, but a few experimental flourishes remain in The Story of Adèle H., particularly his use of spectral superimpositions, employed every time Adèle experiences a nightmare about the drowning death of her sister. Mostly, though, cinephiles will be drawn to the intoxicating cinematography and production design. Truffaut’s Halifax is a dark, muted, snowy, befogged place against which Adèle sticks out like a sore Parisian thumb, her scarlet frocks blazing in the colorless chill, dramatic and tone-deaf to the world around her.

Sullivan’s Travels: If Sullivan’s Travels (Criterion, $26.19 Blu-ray, $22.99 DVD) isn’t the greatest movie ever made — and one could certainly make a case for it — it’s doubtlessly the best movie about movies ever made. One of the handful of masterpieces Preston Sturges wrote and directed in a feverishly productive four-year period in World War II-era Hollywood, it stars Joel McCrea as John Sullivan, a studio director with a mansion, yachts, a swimming pool and a guilty conscious: Struck by the inequities of the economically battered, war-ravaged world, he approaches his producers with his desire to film a “commentary on the modern condition.”

The problem is, Sullivan was raised in first-world comfort and doesn’t know a thing about the downtrodden. So he grabs a bindle, dresses like a hobo and heads for Hollywood’s hinterlands, attempting to channel the plight of the nation’s dispossessed in his next movie. Along the way, he meets his love interest, credited simply as The Girl (a career-best Veronica Lake), finds himself at death’s door and in a hard-labor camp, and finally learns a fundamental lesson about the value of unpretentious comedy as a palliative antidote to society’s ills.

The film relies on an ingenious three-act structure. The madcap first act boasts some of the snappiest, wittiest dialogue ever filmed; every line is precise and quotable. The second is a road movie, a budding romance and a quest for enlightenment. The third is its sobering tailspin, the moment when Sullivan’s wishes come horrifyingly true. Sturges wrote in enough death, greed and desperation into the film’s final moments that he manages to successfully have his art-film seriousness and mock it too.

There’s so much about Sullivan’s Travels that resonates today: The idea of the rich, well-meaning celebrity lecturing the public about issues with which he has no expertise. The desire of Sullivan’s studio executives to follow him around everywhere and document his quixotic journey as a publicity stunt, thus creating, for a time, a sense of only artificial danger. The concept of comedy as a lower generic caste than social-problem dramas, a theme since explored by Woody Allen’s Stardust Memories, Chris Rock’s Top Five and many others.

Sullivan’s Travels thumbs its nose at noble intentions and deflates the pomposity of so many of Sturges’ contemporaries. Judging by the fact that it’s this profound comedy, and not their self-important harangues, which is still being watched, studied and loved, it’s obvious he’s gotten the first, and the last, laugh.

The Friends of Eddie Coyle: The fatuous ’70s score in The Friends of Eddie Coyle (Criterion, $26.19 Blu-ray, $19.59 DVD) dates the movie to its year of origin, but everything else about this grimly realistic 1973 crime drama feels cut from the same sobering cloth as such modern fatalistic thrillers as The Drop and A Most Violent Year.

A charismatically haggard Robert Mitchum plays small-time gunrunner Eddie “Fingers” Coyle, awaiting trial for a truck hijacking gone awry. In the meantime, he continues to supply firearms to masked bank robbers while trying to negotiate a sentencing recommendation from an ATF agent (Richard Jordan) angling for the names of his clients.

The fine journeyman director Peter Yates, shooting entirely on Boston’s less desirable streets, banks, bars and tenements, envisions a world that’s rotting from the inside — a environment of villains, backstabbers and antiheroes that perfectly captures Vietnam-era cynicism. Its elemental, matter-of-fact brutality presages Tarantino as much as it channels the Lumet dramas of the period (one key character is named Jackie Brown), and we’re left pulling for Coyle simply because Mitchum earns our sympathy.

It’s a performance of nuanced pathos in which actor and character become one and the same; Eddie’s ragged clothes and understated Beantown accent cling to Mitchum like a blanket of cigarette smoke. The actor turns his boozy criminal into a tragic patsy, and the effect is that of an old-fashioned, impenetrable movie star thrust into a punishing new world, forced to accept that he cannot change his destiny. Mitchum shot plenty of movies after this one, but few of them gave the actor so many harsh truths to digest. There are no new additions on this beautiful Blu-ray that weren’t featured on Criterion’s sparse 2009 DVD release, but Kent Jones’ accompanying essay on the film’s unusual merits — and the thrilling backstories of some of its ensemble actors — is one of his best.

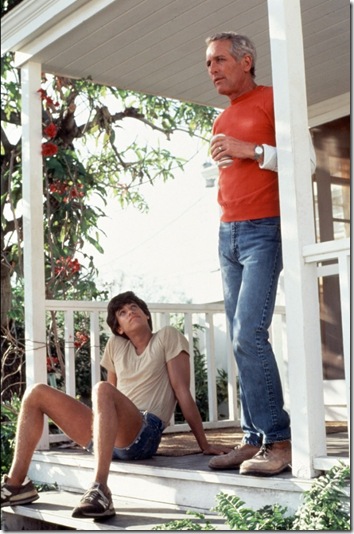

Harry and Son: Released in 1984, Paul Newman’s Harry and Son (Olive, $19.45 Blu-ray, $18.93 DVD) isn’t usually mentioned among the definitive South Florida films, even though it was shot largely in Lake Worth. That’s probably because the Palm Beach County of Newman’s drama could be Anywhere U.S.A., with its opening images — a slow-motion wrecking ball majestically demolishing a historic building — serving as an apt metaphor for lives crumbling in an atmosphere of social malaise and economic contraction.

Newman cast himself as the widowed Harry Keach, who lives with his college-age son Howard (Robby Benson) and operates the crane that controls the fate of said building. Still numbing the pain of his wife’s two-year-old passing with alcohol and ignoring increasingly invasive vision problems, he soon loses his job. Moody, taciturn, and unable to find another position in construction, Harry piles his unmet ambitions and unspoken resentments on Howard, a struggling writer who makes ends meet at a dead-end car wash.

The few films Newman directed over his 50-year career speak to his sensitive side as a dramatist. His was an interior vision, unafraid to favor emotions over actions, character over plot. In this regard, Harry and Son is just as unimpeachably solid as his earlier Rachel, Rachel and The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds — both starring his wife Joanne Woodward, who contributes a touching supporting role in Harry and Son. This is a film about coping with life changes for which we can never be adequately prepared: grief, illness, joblessness, fatherhood, death. These are big issues delivered in a low-key package and leavened with effective, and unexpected, humor.

The Fantasticks: Michael Ritchie’s unshapely 1995 adaptation (Twilight Time, $29.95 Blu-ray) of Tom Jones and Harvey Schmidt’s record-breaking off-Broadway musical sat on the shelf for five years before it saw a limited release, where it earned just $49,000 back on its $10 million budget. Many would say it was fundamentally doomed from its inception: Like Our Town, The Fantasticks is a work so tethered to the nuts and bolts of stagecraft that it would seem to be film-proof.

Joel Grey and Brad Sullivan play the scheming next-door neighbors — single fathers who unnecessarily try to forge an already blossoming romance between their children, Luisa and Matt (Jean Louisa Kelly and Joey McIntyre). Their method involves hiring the bandit El Gallo (Jonathan Morris), who has just erected a tacky carnival in the middle of their prairie, to stage a mock abduction of Luisa, wherein Matt will save his damsel and win her heart. The plot goes off swimmingly but trouble follows, as domestic life proves less than fulfilling for the two young lovers, and Luisa’s affections drift toward El Gallo.

Grey and Sullivan are the best actors here, in part because all of the others still act like they’re performing on a stage, not in front of cameras. Ritchie’s tone waffles between farce and melodrama, stumbling across a thin line that great productions of The Fantasticks walk with aplomb. There are some nice, dark touches late in the game, such as a trippy gondola ride through El Gallo’s torture dungeon of a circus, but it feels lifted from a different movie. There’s no better sign of this movie’s tone-deaf confusion than the fact that the musical’s signature song, “Try to Remember,” isn’t deployed until the final scene, as a throwaway postscript.

Oh, would that Johnny Depp would have played El Gallo under Tim Burton’s direction. It probably still would have failed, but it least it would have been interesting.