Li’l Quinquin: We’re barely 10 minutes into this three-and-a-half-hour Bruno Dumont epic (Kino, $22.99 Blu-ray, $19.99 DVD), and surrealism has gripped us for the long haul: A helicopter airlifts a cow from its resting place in a seemingly inaccessible bunker, a shot as majestically strange as the Christ statue hovering over the Roman aqueduct in La Dolce Vita. Only this symbol is stuffed with partially devoured human remains.

So begins a macabre murder mystery in a quaint French seaside town whose central character, Quinquin (Alane Delhaye), is a resourceful, defiant, troublemaking child with intense eyes, the sneer of a pint-sized James Cagney and, most surprisingly, an adult’s capacity for empathy. He’s a frequent thorn in the side of Commandant Van der Weyden (Bernard Pruvost), the shambolic and twitchy sheriff assigned to the bizarre case, along with his dentally impaired lieutenant (Philippe Jore). The corpse in the cow is the first of many: As the bodies pile up, discovered inside weirder places and animals, chief suspects become victims, each lead sifting through the detectives’ fingers like so much sand on the nearby beach.

For his part, Dumont seems in no hurry to solve the case. No stranger to police procedurals — Humanité is one of the great French films of the past 20 years — this time he largely eschews psychosexual suspense in favor of a lighter, diversionary touch. He spends the movie’s hulking running time (it originally ran as a miniseries on French television) just hanging out with Van der Weyden, Quinquin and the surrounding locals, as they ride horses, chat about provincial proverbs, light inappropriate firecrackers and enter singing competitions.

There is much humor in their interactions, from a hilariously sloppy funeral sequence to an absurd interlude in which a child in a makeshift superhero costume pesters Quinquin’s developmentally disabled uncle. But Dumont’s observance of this town also reveals a festering culture of xenophobia directed at its Arab minority. The humor of Li’l Quinquin is persistent, but so is the dread that slowly gathers around the movie’s fringes, disarming us.

Many may be unsatisfied by the film’s anticlimax, but Li’l Quinquin deserves a wider audience than it will receive. It’s the most accessible picture I’ve seen yet from Dumont, and its milieu — perverse crimes rattle a small town — links it to hilarious whodunits like Twin Peaks and the black comedies of the Coen Brothers. After 206 minutes, I can genuinely say I wanted more.

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders: A capstone of the Czech New Wave movement that flourished in the late ’60s, Jaromil Jires’ Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (Criterion, $22.99 Blu-ray, $17.49 DVD) is like a Disney fairytale as interpreted by Russ Meyer or Jesus Franco. This dreamfilm begins with the title character (Jaroslava Schallerová, then 13 years old), an orphan living with her grandmother, asleep in a gazebo. Her future love interest of sorts, a man named Eaglet, creeps into her space, wielding a flaming staff and stealing her symbolically significant earrings. Weirdness continues the following morning, when a charismatic monster arrives in a wedding caravan. Soon enough, Valerie’s spectral grandmother strikes a Faustian bargain for eternal youth and transforms into a sexy vampire; mind you, this was before sexy vampires became universal tween bait.

Valerie is like Alice, slipping down an especially deviant rabbit hole. Just about every recurring character represents sexual predation, and when she’s not being preyed on herself, Valerie voyeuristically gazes upon the carnal whims of naiads, her grandmother’s sexual transgressions, and other acts of public copulation, while seeking solace in her virginal white bedroom, built like an oversized dollhouse.

Jires never tells his audience what to think, and Valerie never coheres into a linear narrative.

In his supplementary interview on this disc, Czech film scholar Peter Hames astutely points out that “it’s a film that you should be prepared to be surprised by.” I see it as a young girl’s nightmare about the panic of puberty, as a scary world of sexual possibility blossoms around her. When Valerie’s blood drips onto fresh daises in an early scene, it’s indicative of menstruation, presented more artfully and abstractly than, say, Carrie’s shower period in the opening of De Palma’s classic shocker. There’s also a Biblical connection in Valerie in Her Week of Wonders; the monster isn’t a snake per se, but Valerie wiles away her hours in an edenic town square, and she certainly eats a lot of apples over the course of the film.

No matter what you take away from it, Valerie is a remarkable experiment, ungrounded from the conventions of storytelling and unbound from the rules of traditional film grammar. It’s a liberating hodgepodge of disorienting genres, shot in dramatic high and low angles, through cobwebs and gardens and peepholes, with an imaginative score and a color palette that seems to reinvent the rainbow. If you buy this disc, which includes three early short films by Jires, interviews with two of the actors, and an alternate psych-folk soundtrack recorded in 2007, you’ll surely watch it more than once.

Jamaica Inn: Disparaged as one of Alfred Hitchcock’s weakest films, this 1939 adaptation of the Daphne Du Maurier novel (Cohen, $24.74 Blu-ray, $20.19 DVD) is ripe for a reevaluation, and in this 4K restoration from Cohen Media in honor of the film’s 75th anniversary, even the slower portions are a pleasure to absorb.

Set in Cornwall in 1819, the Jamaica Inn of the title is introduced in a close-up of its wooden sign — as creakily inviting, in its 19th-century English gothic way, as the Bates Motel was in mid-20th century American suburbia. The space isn’t so much a quaint B&B as a medieval dungeon, and Hitchcock’s emerging authorial voice is most present in its foreboding architecture: The building oozes the angular menace of early German Expressionist production design.

The oceanside inn is run by Joss and Patience Merlyn (Leslie Banks and Marie Ney) as a front for Joss’ piracy ring; his team of smugglers cause shipwrecks, plunder the loot and leave the sailors for dead. It’s a well-oiled scheme with evergreen profits —that is, until Patience’s niece Mary (a relatively unknown Maureen O’Hara, framed like a goddess by Hitch) catches wind of the secret. The corruption traces back not to her casually monstrous step-uncle but to the town’s squire, a refined, corpulent devil played by Charles Laughton.

For the most part, Hitchcock is more of a craftsman and translator than an artisan, and the film still suffers from its tedious stretches of ill-paced patter delivered at an incomprehensible clip by cotton-mouthed character actors. Even Cohen’s immaculate visual restoration can’t turn the movie’s audio lemons into high-fidelity lemonade. But some of Hitchcock’s camera whips and jolting edits suggest an inchoate artist boxed in by the less-than-desirable source material. The movie’s opening scenes are masterful, evoking in a studio the intensity of a shipwreck, as pitiless waves bombard a teetering vessel with miniature tsunamis — Hitch’s camera swaying, seasick, to the action.

This earthy adventure story doesn’t reach these thrilling heights again, but the fact that conservative commentator and one-time film critic Michael Medved considered Jamaica Inn one of his 50 Worst Films of All Time is further proof not to listen to Michael Medved.

The Pillow Book: First of all, this release (Film Movement, $24.19 Blu-ray, $16.05 DVD) should be lauded: It represents the esteemed world-cinema distributor Film Movement’s first foray into back-catalog titles and — I believe — to Blu-ray discs in general. And I for one can’t wait to see what forgotten world-cinema gems will emerge as the Film Movement Classics imprint continues.

For all its faults, this release of The Pillow Book looks great. But boy, do those faults pile up. Eccentric writer-director Peter Greenaway’s provocative attempt at art-house erotica fails grandly as both, despite pushing the medium of film in indisputably new directions.

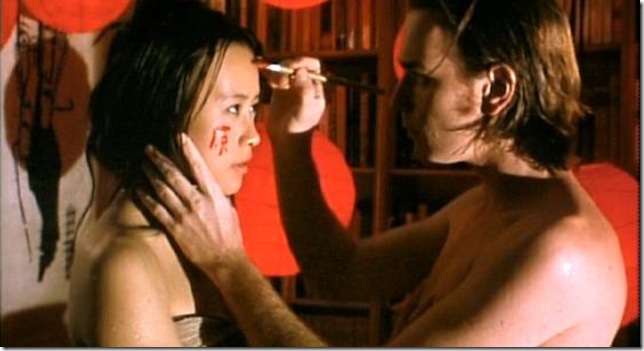

Vivian Wu stars as Nagiko, a Japanese model whose passion for her native

calligraphy extends into a most peculiar sexual fetish. She seeks partners who will write perfect verse on her body — and will let her do the same — eventually finding a suitable partner in Ewan McGregor’s English translator, Jerome.

Greenaway’s trademark fastidious framing is presented in its full symmetrical glory, but The Pillow Book’s approach is more experimental than most anything he’s directed. There are jarring transitions from black-and-white to color to sepia imagery, and from widescreen to the academy aspect ratio. There are frequent superimpositions, scrolls of onscreen text and picture-in-picture distractions. The movie reflects a restless boredom with film grammar, its maker overstuffing his canvas with more ideas than are fit to observe even on a giant screen, let alone a home theater.

Whether you appreciate its radical formalities or not, it’s hard to take seriously The Pillow Book’s content, which helped establish McGregor’s reputation as the most willing nude-scene participant in mainstream film history but which is filmed by Greenaway as soft-focused outtakes from the Emmanuelle franchise. The film descends into risible slapstick whether it intends to or not, as imagery that could once be accepted as hypnotic grows to be facile and irritating. The movie’s formal filigrees mask its fundamental vacuity, leaving us with a few strikingly surreal set pieces. Which, needless to say, cannot sustain two hours and seven minutes.

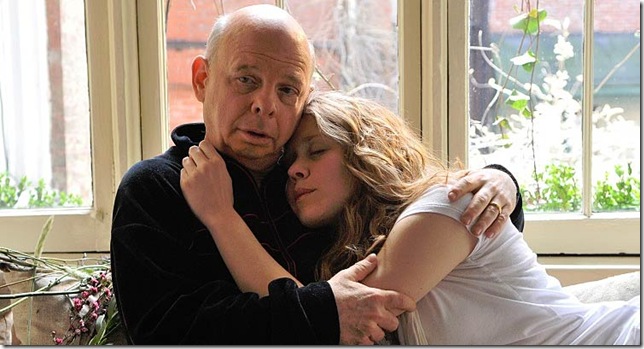

A Master Builder: One of Henrik Ibsen’s most dense, symbolically loaded plays receives an appropriately challenging and surreal film adaptation in Jonathan Demme’s A Master Builder (Criterion, $22.99 Blu-ray, $19.99 DVD), based on the same creative partnership between Andre Gregory and Wallace Shawn that gave us My Dinner With Andre and Vanya on 42nd Street.

Adapted from Gregory’s stage version — which was some 14 years in the making —an irrepressible Shawn stars as the title character, architect Halvard Solness, who in his twilight years refuses to accept his encroaching obsolescence. An ethereal visit from a young, unhinged semi-stranger named Hilde (Lisa Joyce) awakens repressed memories in Halvard and forces him to confront buried demons of a historical and metaphysical nature.

The plot sounds as thin as an architect’s blueprints, but the result is as sturdy as a mansion. With acting this flawless — there is such devious, cunning intelligence in each of Shawn’s marbled gazes, and as his wife, Julie Hagerty powerfully expresses Ibsen’s trenchant feminism — the film’s 127 minutes soar by in a monumentally engrossing psychological horror show teetering on the border between genius and madness.

Gregory and Shawn’s theatrical version contains a brilliant new twist on the 19th-century source material, and Demme honors it through his radical formal decisions. Tight, docu-like bookend scenes, stripped of Hollywood gloss, bracket a lavish, CinemaScope middle portion bathed in golden light. Demme, clearly infatuated with the material, also experiments with editing, camera focus and camera movement —his zooms have a pointed, jabbing quality — but mostly films this spellbinding drama as an immutable symphony of close-ups. You won’t soon forget it. The Criterion edition contains three generous supplemental interviews with the cast and creative team, and the movie is also available in a Criterion box set with My Dinner and Vanya.

Beloved Sisters: Director Dominik Graf’s epic biopic (Music Box, $24.99 Blu-ray, $18.07 DVD) about the 18th-century German poet Friedrich Schiller is a stately, handsome, literary prestige picture — descriptors that can sound like a laud or a dismissal depending on the viewer. Graf admirably centers the tale not on Schiller (Florian Stetter) but on the two women in his life: Charlotte von Lengefeld (Henriette Confurius) and her sister Caroline (Hannah Herzsprung), who fell in love with the penniless poet at the same time. Schiller would go on to marry Caroline but remain most passionately amorous for Charlotte, ripping a once-unbreakable triangle into disconnected shards of betrayal and resentment.

Graf, who also wrote the screenplay, provides his tragic story plenty of breathing room, using all of the movie’s 171 minutes to present a broad, realistic narrative arc of ideals disavowed and bonds broken. He’s just as skilled at depicting exchanges of unspoken smolder as he is the film’s talky passages (and there are many), and his evocation of the storming of Bastille — a shot of cobblestones running crimson — is potent and unforgettable. Too often, though, he settles for middlebrow film grammar, like exhaustive voice-over narration, inserts of maps to evoke travel, and a manipulative score. Still, Beloved Sisters is heartbreakingly alive to the ways circumstances, accidents and temperaments can tear unions apart; if it tends to spell out its conclusions, at least it does so poetically.

She-Devil: Susan Seidelman, of Desperately Seeking Susan fame, directed this strychnine-laced 1989 comedy of the “hell hath no fury…” subgenre (Olive, $19.99 Blu-ray, $17.99 DVD). Roseanne Barr plays faithful housewife Ruth Patchett, a slovenly caricature with a warty visage, who grows a moustache and keeps a carton of Dunkin’ Donuts on her nightstand. When her sleazy accountant husband (Ed Begley Jr.) strays from her arms in favor of the golden locks and come-hither gaze of pampered romance novelist Mary Fisher (Meryl Streep), Ruth brings out her inner she-devil, orchestrating an elaborate plot to destroy her husband’s four cherished “assets:” home, family, career and freedom.

Seidelman takes a scenic route to reach this protracted comeuppance, littering the inevitable plot with transparently ’80s gags — dead rodents showing up in casseroles, lewd papers spilling from copy-machine sex, the screeching sounds of pets injured off-camera. It’s only a matter of time before a moment of implied oral sex between Streep and Begley is interrupted by a harsh edit to Ruth violently chopping a zucchini. You get the picture.

Streep almost singlehandedly keeps this dated infidelity satire afloat. She adopts the theatrical, faux-sultry breathiness of a ’40s femme fatale, and she succumbs fully to the outsized slapstick the story requires. Streep long ago stopped taking roles like this, and it’s easy to see why, but the anarchic flames of She-Devil burn the brightest when she’s onscreen.