The Kindergarten Teacher: There’s a lot to uncrate in Israeli director Nadav Lapid’s implacably disturbing The Kindergarten Teacher (Kino, $22.99 Blu-ray, $19.99 DVD), so let’s start with the pupil. Yoav Pollak (Avi Shnaidman) is a 5-year-old student in a Tel Aviv kindergarten who possesses the soul of a great poet.

Most of the time, Yoav is a normal tyke, playing in the sandbox and on the jungle gym, chanting off-color sports anthems with his best friend, sleeping easily during naptime. But every now and then — once or twice a week, says his nanny — he enters a sort of trance, paces back and forth, and speaks breathtaking poetry about things beyond a 5-year-old’s ken: faith, bullfighting, vengeance, Chinese philosophy, the limits of beauty, the inevitability of parting. Each poem feels like a transient transmission, downloaded from somewhere else and passed down orally by the lucky few adults within earshot.

The justification for this precocity, never implied by Lapid but inferred by this critic at least, is that Yoav was a poet in a past life, and these snippets of Zen represent the vestigial remains of his soul’s former occupant. It’s a romantic notion, and most Hollywood treatments of this character would centralize his gifts under scientific and ethical microscopes, stripping him of his magic. In The Kindergarten Teacher, this phenomenon is merely the ambiguous subtheme to a larger study in obsession, hypocrisy and exploitation by the adults in Yoav’s life.

His teacher Nira (Sarit Larry), a lesser poet herself who has two grown children and a husband from whom she’s drifting apart, sees in Yoav’s ability a cure, perhaps, for the emotional and intellectual vacancies in her own life: It’s not for nothing that in the first few images of Nira, Lapid photographs her from the neck down, as a figure without an identity. She visits the men in Yoav’s splintered family, discovers that none are nurturing his talent, and takes many steps too far to preserve it herself.

It’s not uncommon, of course, for a teacher to show extra interest in a special child, to water a flower that is clearly wilting at home. The Kindergarten Teacher wouldn’t work if there weren’t a seed of nobility in Nira’s actions. Lapid shows us the gradual disintegration of good intentions, fueled as much by professional envy as existential malaise.

In just his second feature, Lapid achieves these objectives through a remarkable command of his camera. The Kindergarten Teacher contains indoor-to-outdoor tracking shots of unusual care and foresight; 360-degree pans around a central point; confrontational, direct-camera close-ups; elegant whip pans and at least one pointed zoom. Those looking for it will see the influence of Kubrick, Antonioni and the Dardenne Brothers. Like those directors, Lapid never tells us how we’re supposed to feel about any of these scenes, leaving us to decipher this increasingly unnerving film.

Tangerine: Reportedly shot on an iPhone 5, for a mere $100,000, on the sun-bleached streets of Santa Monica, Sean Baker’s Tangerine (Magnolia, $20.99 Blu-ray, $19.49 DVD) is a loud, caterwauling, unflinchingly honest triumph of outsider art. This roiling movie is populated entirely by characters living on life’s margins, the sort cautiously ignored by Hollywood — namely a pair of transgender prostitutes, Sin-Dee Rella and Alexandra (first-time actors Kitana Kiki Rodriguez and Mya Taylor, respectively, whom the director met while researching his script at an LGBT center in Los Angeles).

It’s Christmas Eve, and Sin-Dee has just been released from a 28-day prison sentence — an occupational hazard of her extralegal profession — only to find out that her boyfriend, a pimp and drug dealer who works out of an all-night doughnut shop, has been sleeping with a white woman (a “fish,” in trans parlance). She embarks on an all-night quest to hunt him down and confront him, as well as his alleged hooker paramour, which will test her friendship with Alexandra.

No less entrenched in this particular L.A. subculture is Razmik (Karren Karagulian), a married Armenian cabdriver with an adulterous preference for trans women.

Baker’s cinematography has the rough-and-tumble rawness of a ‘90s rap video, often aided but a spastic soundtrack of crunching EDM. It’s off-putting at first, but once you settle into its groove, it’s impossible to look away. Against the bedraggled backdrop of the finest bail bonds establishments, strip malls, coin laundries, Quick-E-Marts and used-car lots of West Hollywood, laws and hearts are broken, insecurities are exposed, unconventional alliances are struck and families are possibly torn asunder.

Yet, as Baker found out in the process of telling his nonjudgmental story, trans prostitutes use humor as coping mechanism to transcend hardship, so this is the prevailing emotion of this scorching docu-comedy — that rare American movie that is like nothing else before it.

Mr. Holmes: Bill Condon’s postmodern take on Sherlock Holmes (Lionsgate, $15.98 Blu-ray, $11.60 DVD) finds the 93-year-old detective (Ian McKellen) retiring to a self-imposed exile on a countryside apiary, with only a housekeeper (Laura Linney) and her precocious son (Milo Parker) to keep him company.

He walks with a cane, his face is splotched with the evidence of his twilight years, and dementia encroaches on his steel-trapped memory — though he’d like nothing more than to finally close the book on his final, unsolved case from 30 years in the past.

Despite his protagonist’s increasingly unreliable memory, Jeffrey Hatcher’s unpredictable screenplay, based on Mitch Cullen’s A Slight Trick of the Mind, layers flashback upon flashback, piecing together a metaphysical mystery that grapples with the very concept of mortality that weighs so heavily over its stooped sleuth. McKellen’s Holmes waxes existential and unloads a career’s worth of regrets into what is arguably the most human Sherlock interpretation ever brought to the silver screen.

The film also posits a Holmes eager to reflect on and wrestle with his own legend, for better or worse, attempting to correct the record on both Watson’s hagiographic stories and their melodramatic film adaptations. He signature hat and pipe were “an embellishment of the illustrator,” he tells a fan disappointed to see him donning an uncharacteristic stovepipe. And after attending a retro screening of one of the early Holmes movies, he comments that, “every plot twist came with a twirl of the moustache and ended in an exclamation mark.” The same is never true of this imaginative, compassionate meditation on life, death and mythmaking.

Do I Sound Gay?: This amusing, enlightening documentary (MPI, $16.85 DVD) chronicles the attempts of its narrator, the Brooklyn-based writer David Thorpe, to shed his perceived “gay voice,” the arching and nasally affect that he describes early on as “like a pack of braying ninnies.” His personal excavation, fueled by insecurities about remaining outside the hetero “norm,” includes man-on-the-street interviews, visits with his family and his own history, lessons from vocal coaches and speech pathologists sit-downs with out celebrities like Dan Savage, Margaret Cho and George Takei—all of whom inevitably must answer Thorpe’s title question.

One could easily do without some of the diaristic navel-gazing of Do I Sound Gay?, and Thorpe’s documentary style, with its voice-over narration, its immersive premise, and its reaching of tidy conclusions, borrows all too liberally from Morgan Spurlock’s formula. But the movie’s pop-cultural diversions, including a convincing presentation of Disney cartoon villains unconsciously modeled after gay men, never cease to fascinate. Ultimately, the film is about Thorpe owning a part of his cultural identity that has been degraded by decades of stereotyping, and building confidence in the process. To this effect, leave it up to David Sedaris to musingly offer the film’s most profound observation; you’ll know it when you hear it.

Return to Sender: In this rank and unconvincing rape-revenge folderol (Image, $18.04 Blu-ray, $9.74 DVD), Rosamund Pike plays germaphobic, workaholic nurse Miranda Wells, whose proficiency with a scalpel is matched only by her awkward social life. When a co-worker sets her up with a friend, rapist William Finn (Shiloh Fernandez) shows up instead, commits his vile act and is promptly imprisoned—leaving Miranda bloodied, traumatized and, in short order, with a jittery hand, torpedoing her career prospects. So instead of therapy or other more traditional (and saner) healing methods, she befriends her abuser, visiting him weekly in prison in ever more revealing clothing, forming a telephone bond, and eventually kind of, sort of, contracting his talents as a handyman to remodel her porch after his ludicrously early release.

Director Foaud Mikati’s sophomore feature appeals to the lowest common denominator, and it does so with stilted rhythms and a palpable gracelessness in both content and form; the scenes shot inside the prison are acoustically challenged to the point of incomprehensibility. But the film’s most egregious flaw is its tawdry exploitation. For rape victims, there’s hardly a more offensive plot point than the idea of a survivor seducing her attacker as a coping schematic, and Mikati lingers on every salacious detail with cannon-fire subtlety and a misguided erotic aftertaste.

There is finally a method to this trashy madness in the form of a third-act twist, but the titillation leading up to it is inexcusable. I Spit On Your Grave, with which this film shares more in common than either of its makers would like to admit, was unwatchable, but at least it was unwatchably honest.

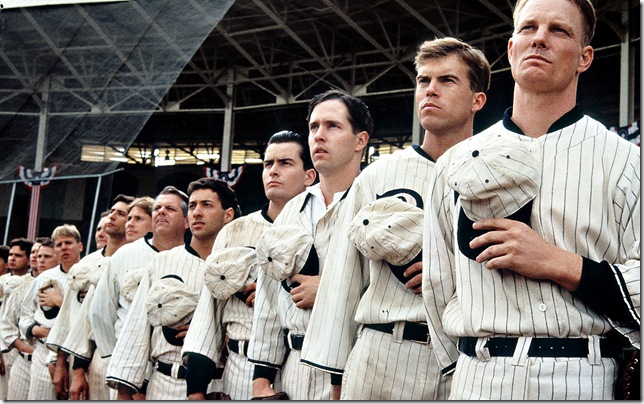

Eight Men Out: Now on Blu-ray for the first time, John Sayles’ addictively watchable account of the 1919 Black Sox scandal (Olive, $26.96) is a great baseball movie, a great history movie and, most resonant today, a salvo against capitalist greed. The enemies, in Sayles’ account (based on Eliot Asinof’s book), are the deceitful, penny-pinching White Sox owner Charles Comiskey (Clifton James), whose underpaying of his all-star team nudged a few of his players to the dark side; and gangsters like Arnold Rothstein (Michael Lerner), who helped transform a bitter gamblers’ con into an atmosphere of corrosive violence.

Even if the Sox themselves, from the ethically bankrupt ringleader Chick Gandil (Michael Rooker) to the tragically roped-in Shoeless Joe Jackson (D.B. Sweeney) to the moral bastion Buck Weaver (John Cusack), come off more as pawns than criminals, the film effectively exhibits an erosion of faith in Major League Baseball, then one of the nation’s sacrosanct institutions, and it anticipates the doping scandals that have plagued it since.

Sayles revels in the sepia-tinged nostalgia of it all, from the bullhorns and old uniforms and fedoras and homemade radios to the inevitable shots of newspapers with damning headlines rolling off presses. You can practically smell this movie — an olfactory mix of leather, money, sweat, ink, sawdust and innocence lost.